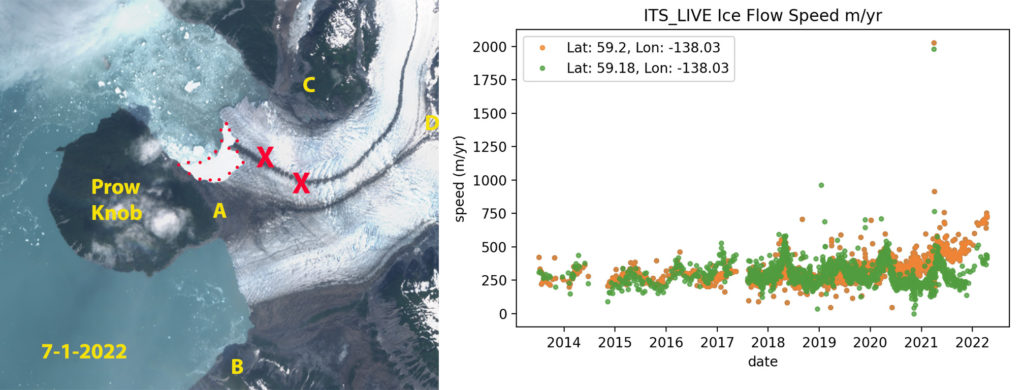

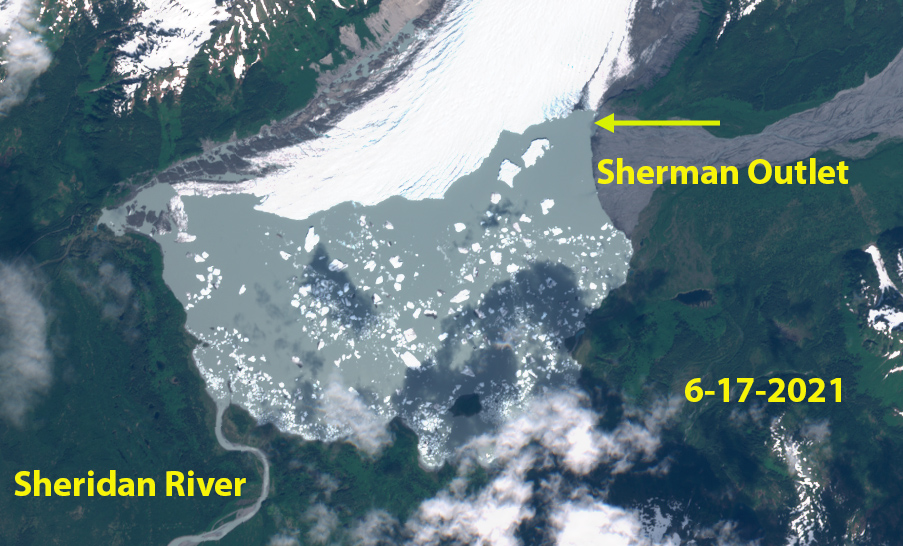

Alsek Glacier, Alaska in a Sentinel Image from July 1, 2022 indicating an area of rapid recent calving, red dots. The northern tongue has accelerated in the last six year (NASA ITS_Live).

Alsek Glacier descends from the Fairweather Range terminating in Alsek Lake on the coastal plain. The glacier terminated at Gateway Knob (G) near the outlet of Alsek River from Alsek Lake in the early part of the 20th century (Molnia, 2005). At that time it had a joint terminus with Grand Plateau Glacier. The glacier retreated 5-6 km by 1984 along the central margin from Gateway Knob. In 1960 the glacier had a single terminus joining downstream of an unnamed island in Alsek Lake, that Austin Post told me reminded him of a boats prow. This “Prow Knob” (P) much like Gateway Knob a century ago stabilizes the terminus. Retreat from this knob will lead to an increase retreat of Alsek Glacier. Loso et al (2021) note that retreat of Grand Plateau Glacier will change the outlet of Alsek Lake from Dry Bay to the Grand Plateau Lake. Here we examine the change from 1984-2022 with Landsat and Sentinel imagery updating Pelto (2017)

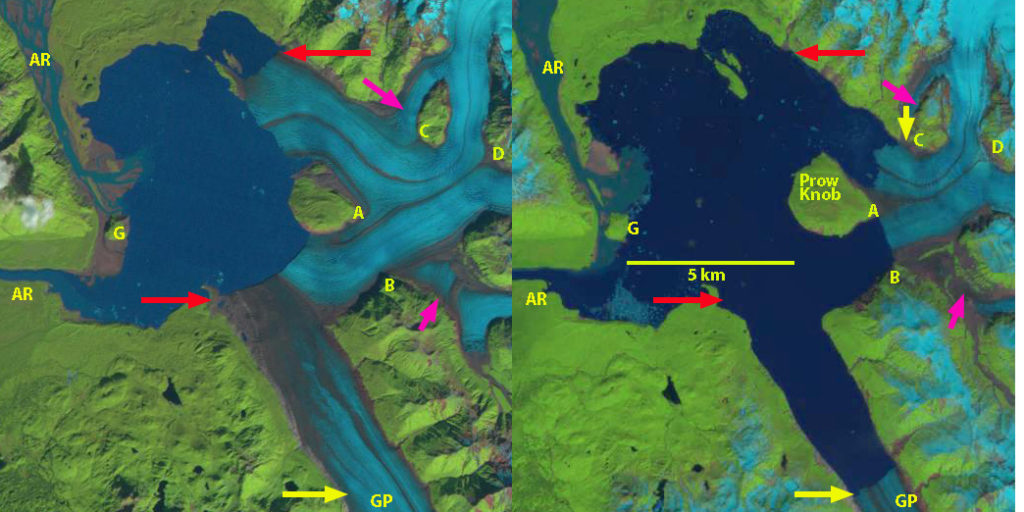

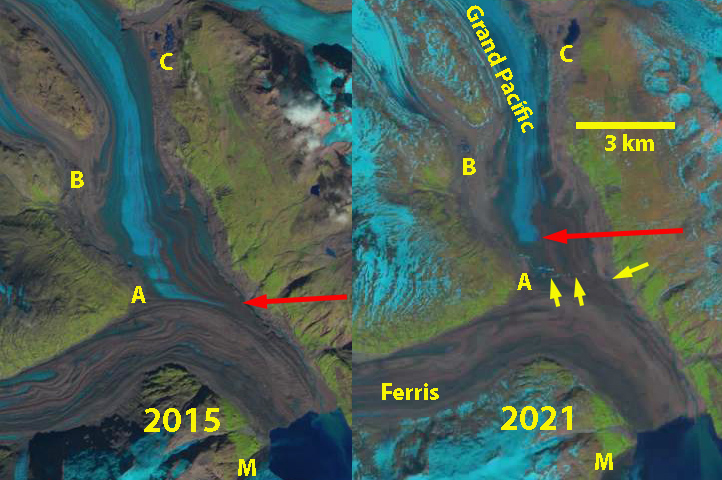

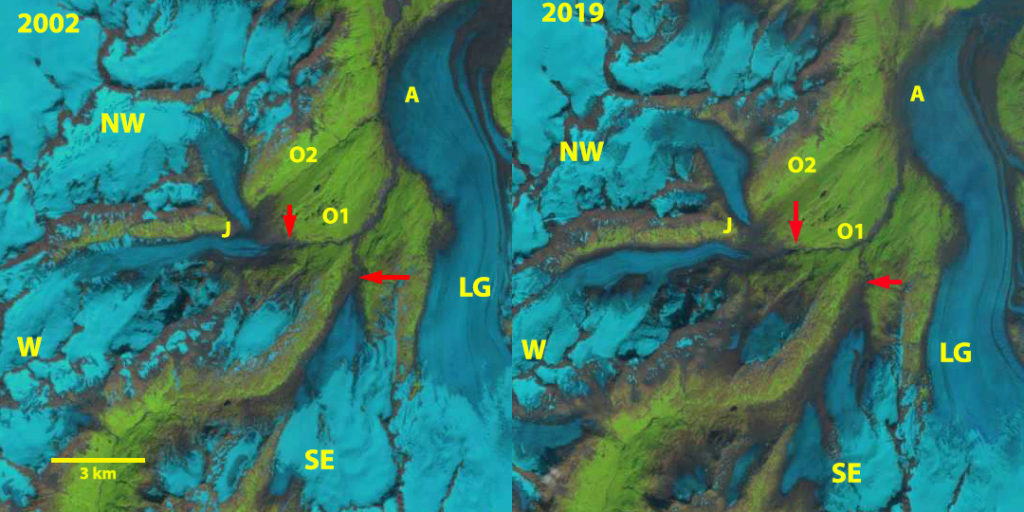

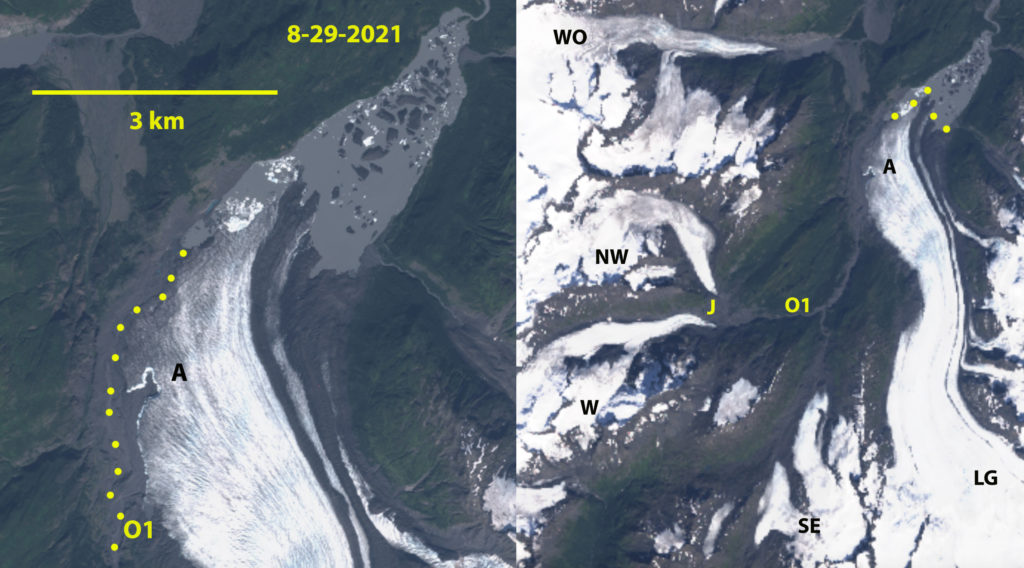

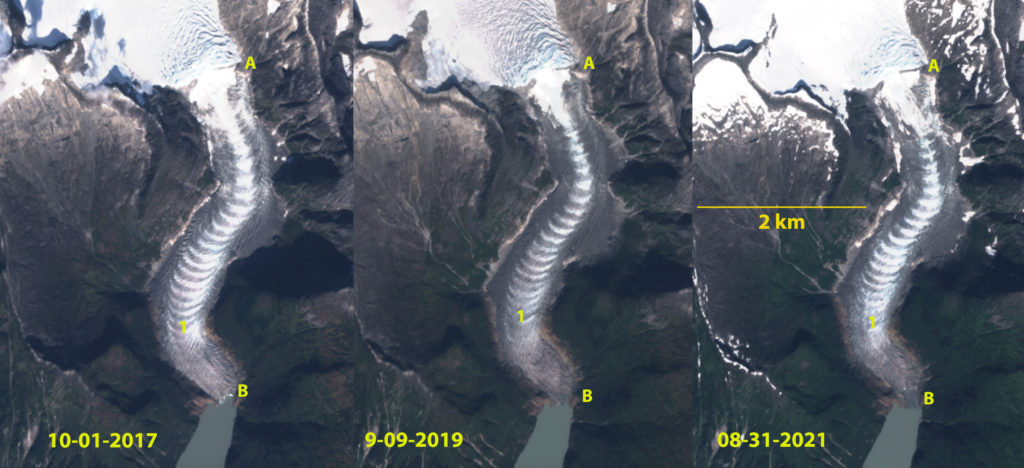

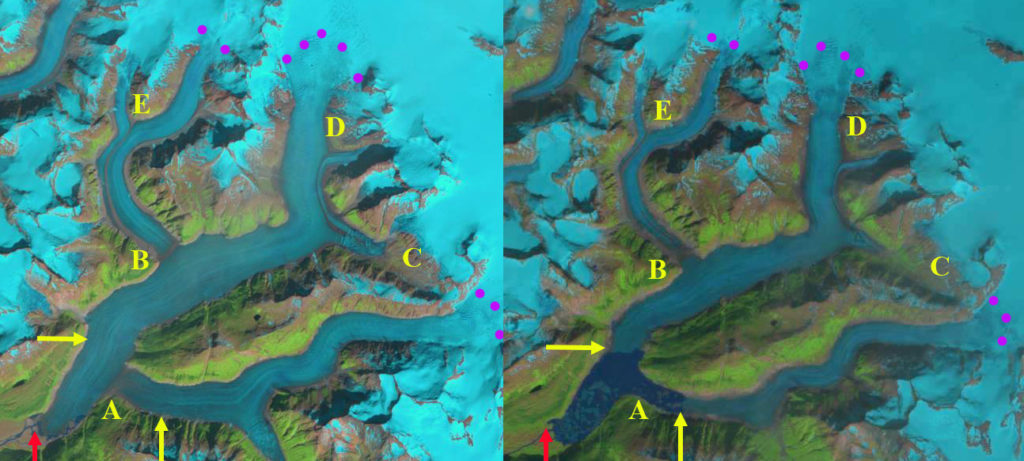

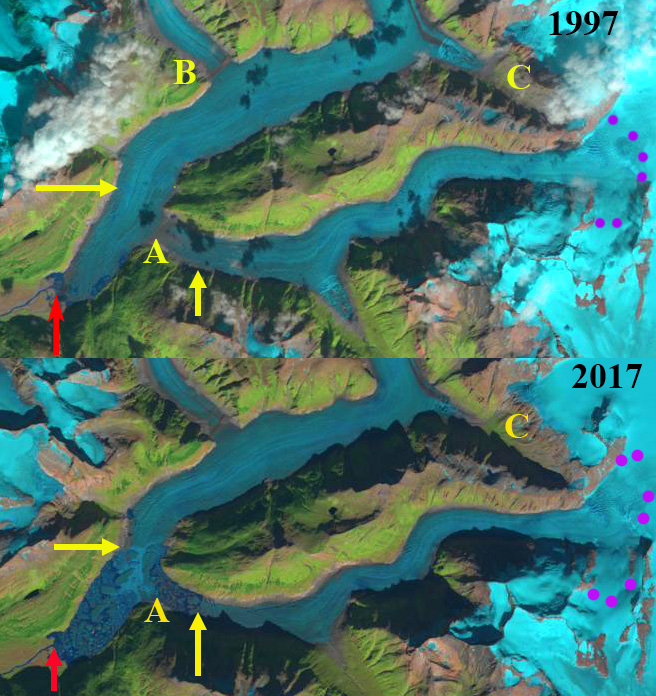

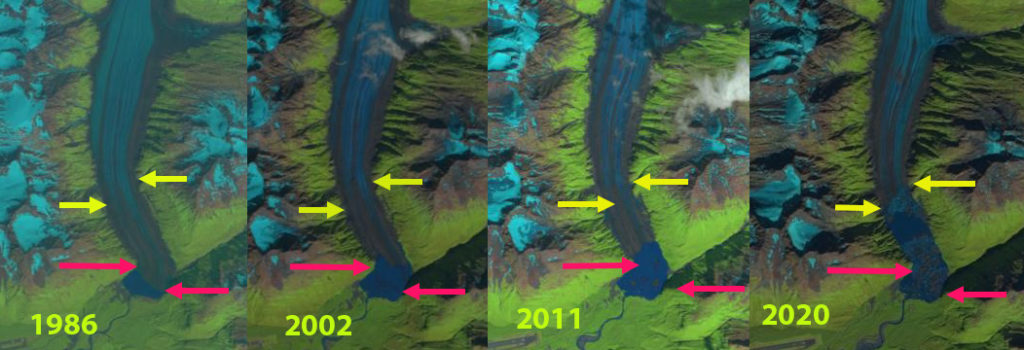

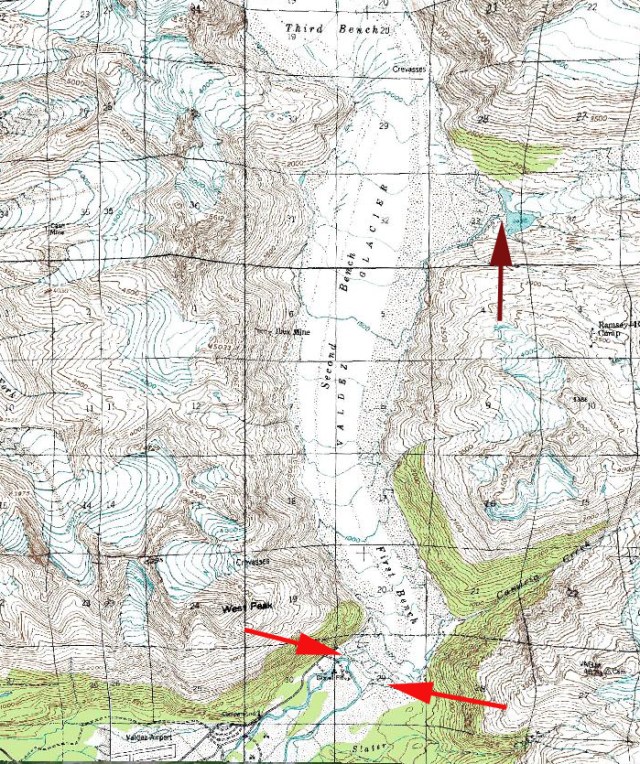

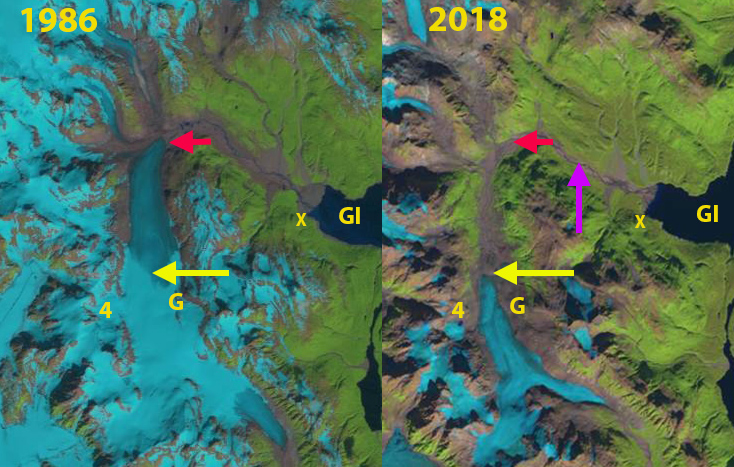

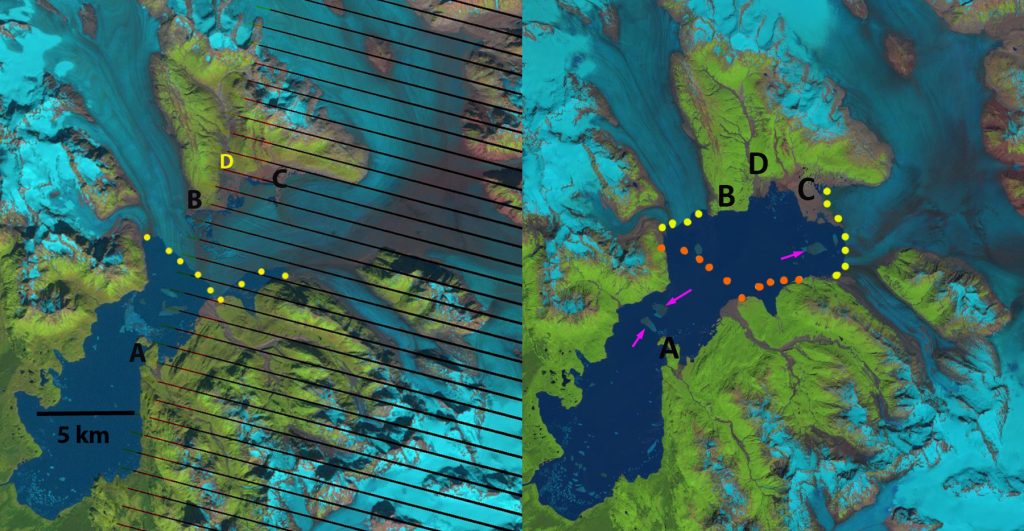

Alsek Glacier retreat from 1984-2022 in Landsat images. Red arrows mark the 1984 terminus location, yellow arrows the 2022 terminus location, pink arrows indicate tributary separation, AR=Alsek River, GP=Grand Plateau, G=Gateway Knob, A=glacier junction, B=tributary separation, C=tributary separation, D=tributary confluence.

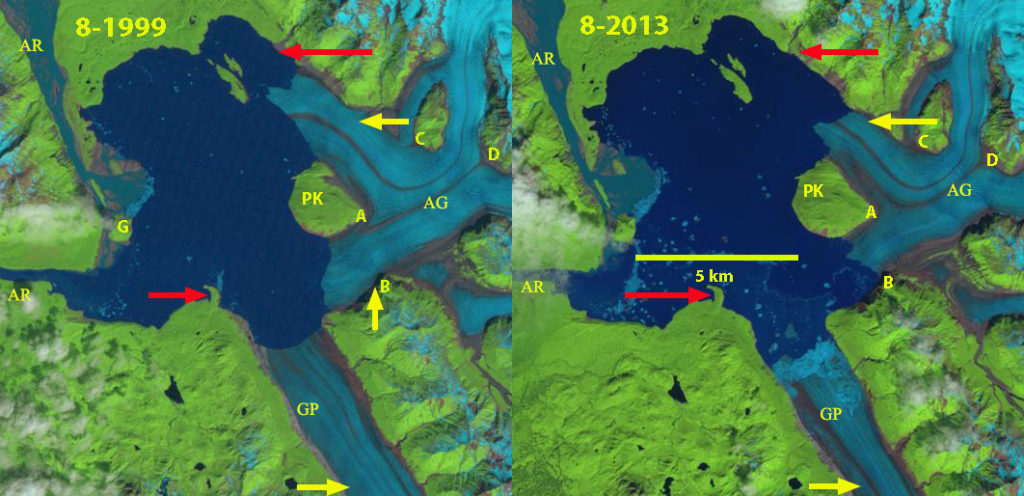

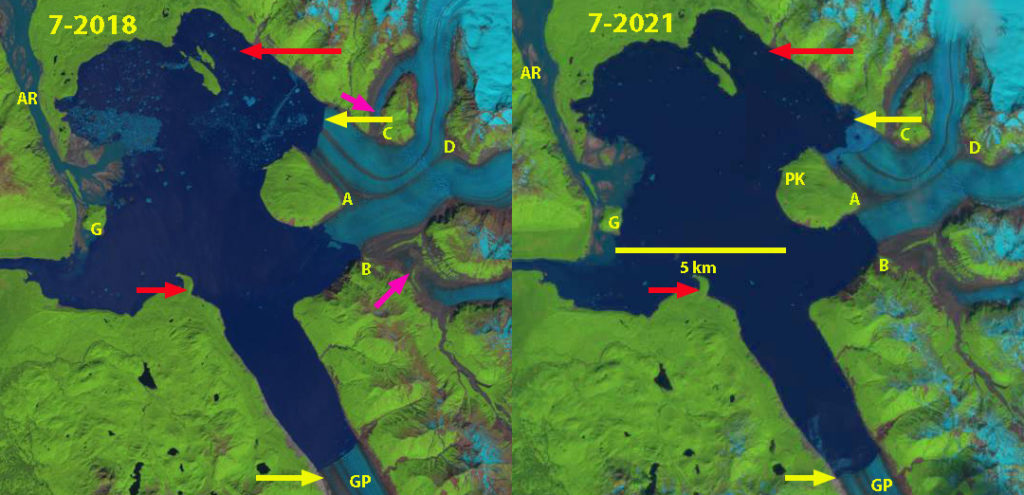

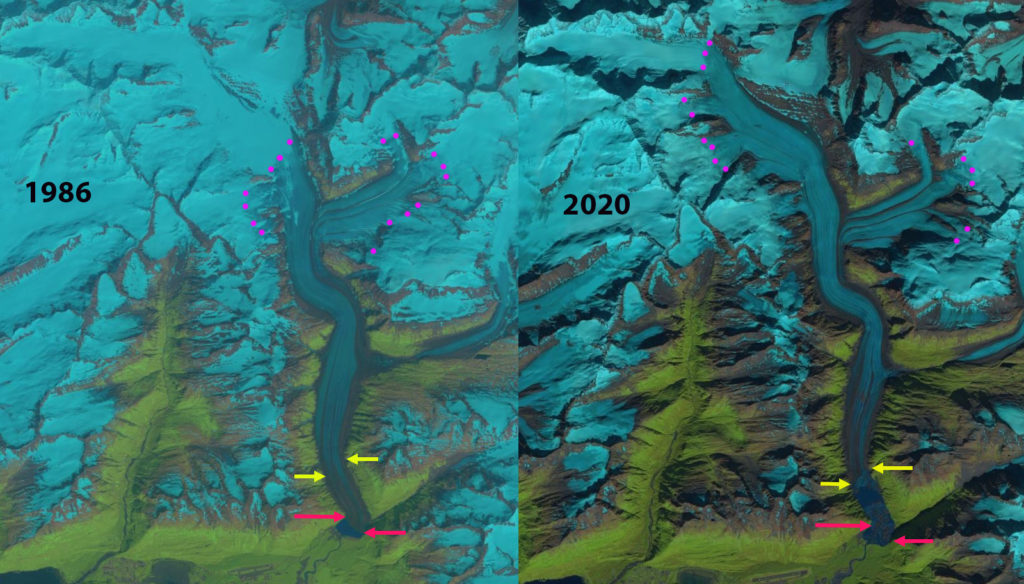

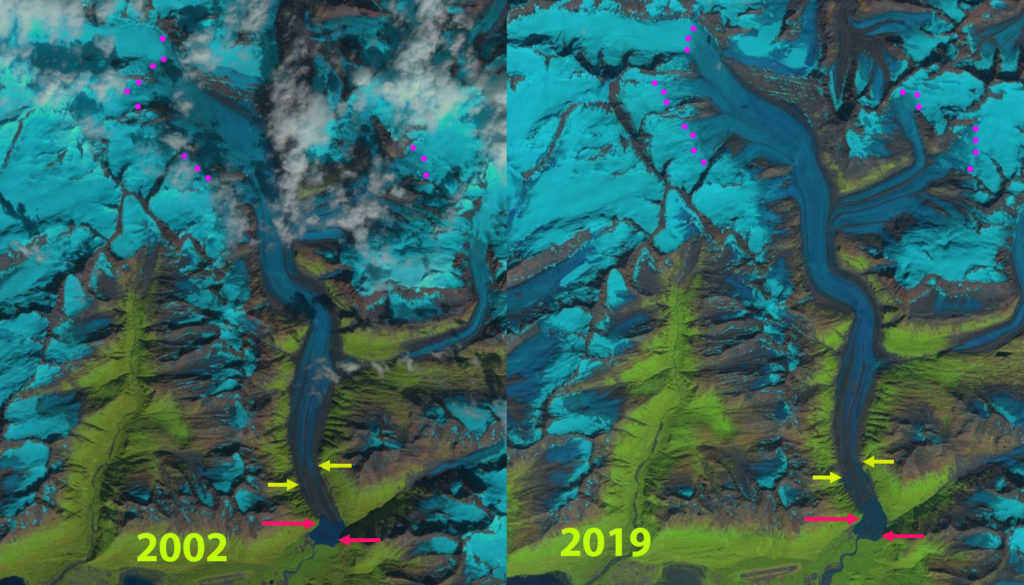

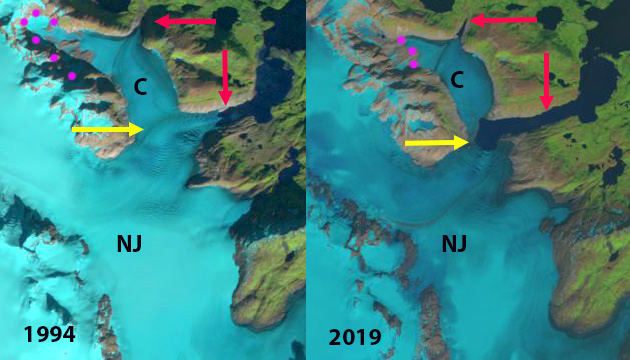

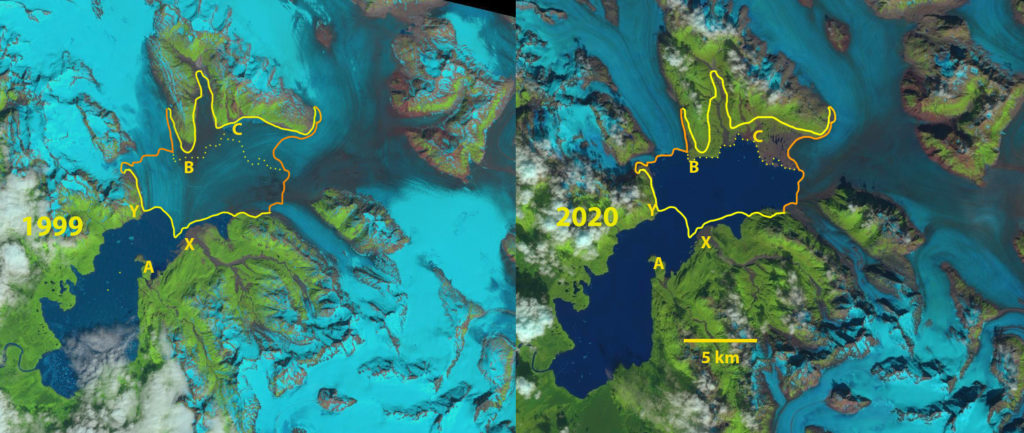

In 1984 the terminus location is denoted with red arrows it has separated into two termini on either side of “Prow Knob”. The northern terminus tongue is located on a narrow island on the north side of Alsek Lake. The southern tongue merges with the northern arm of Grand Plateau Glacier in 1984. Two tributaries at the pink arrows merge with the main glacier. By 1999 the northern tongue has retreated from the narrow island, which exposes the terminus to enhanced calving. The southern terminus has separated from the Grand Plateau Glacier. By 2013 the northern terminus has retreated to the northern end of “Prow Knob” and the southern terminus is directly south of “Prow Knob” in a 1.8 km wide channel. By 2018 two tributaries of Alsek Glacier are fully detached from the glacier, pink arrows. In 2018 the northern terminus tongue has retreated 3.7 km since 1984 into the 2.0 km wide channel on the northeast side of “Prow Knob”. The center of the southern terminus has retreated 2.5 km since 1984 and remains in the channel on the south side of “Prow Knob”. The length of the calving front has declined from an 8 km long calving front in 1984 to a 4 km calving front in 2018. By 2021 further retreat has led to a 2.8 km wide calving front, and a 1.6 km long contact with Prow Knob. From 1984-2022 the retreat and loss of area has been: 4.3 km and 8.6 km2 respectively for the northern terminus, 2.7 km and 5.1 km2 for the southern terminus and 7 km and 13.1 km2 for the northern arm of Grand Plateau Glacier.

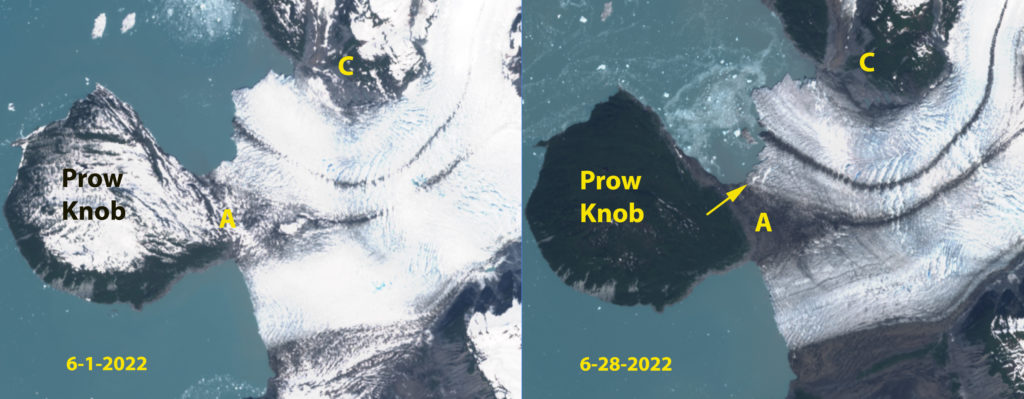

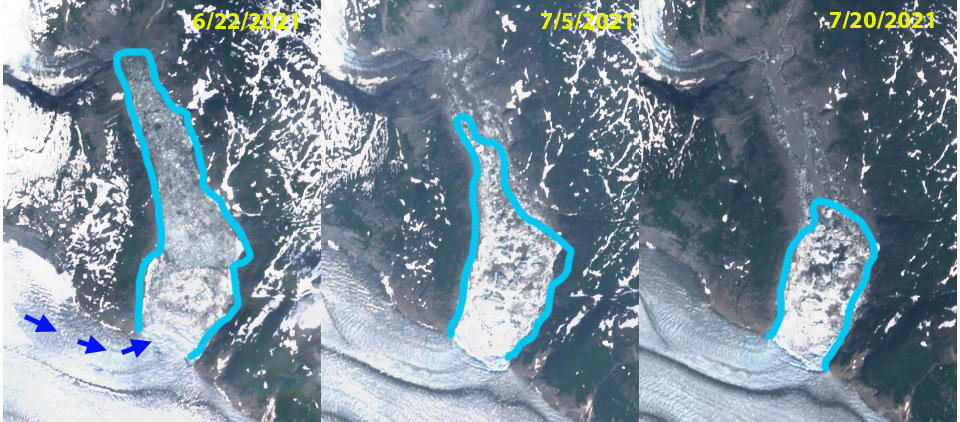

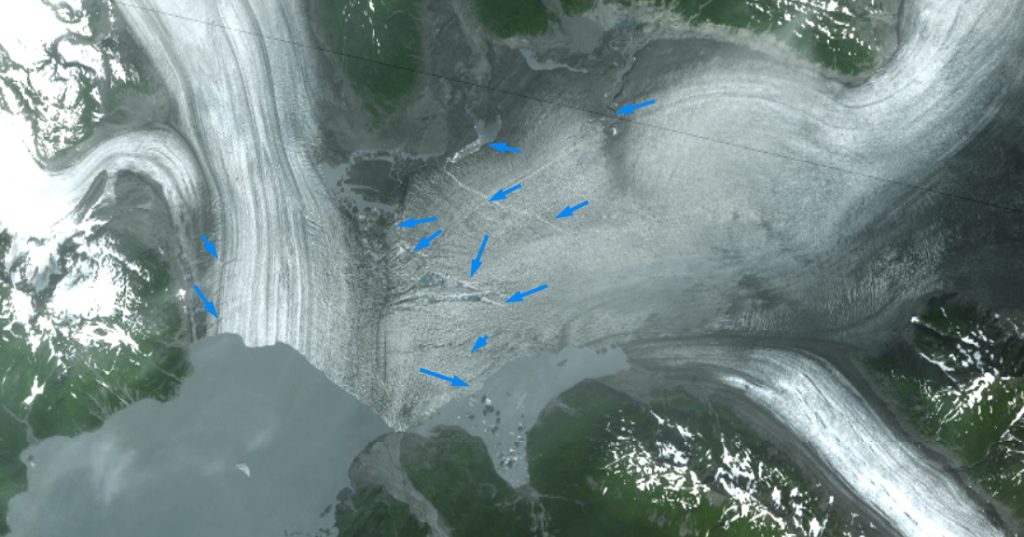

In 2022 the northern terminus arm has accelerated within 1 km of the calving front, note the two red X, marking velocity locations. This has generated additional calving and rifting, that is evident in the June 28 image. The NASA ITS_LIVE velocity measurement tool uses Landsat and Sentinel images to determine velocity using feature tracking. The rifting and acceleration is producing enhanced calving and retreat. The area of enhanced calving on July 1 is 0.3 km2. The acceleration and rifting is typically an indication of a greater degree of terminus flotation that can be due to thinning and/or reduced contact with Prow Knob. This will lead to additional calving events this summer as the glacier progressively detaches from Prow Knob.

Alsek Glacier retreat from 1999-2013 in Landsat images. Red arrows mark the 1984 terminus location, yellow arrows the 2022 terminus location, AR=Alsek River, GP=Grand Plateau, PK=Prow Knob, G=Gateway Knob, A=glacier junction, B=tributary separation, C=tributary separation, D=tributary confluence.

Alsek Glacier retreat from 2018-2021 in Landsat images. Red arrows mark the 1984 terminus location, yellow arrows the 2022 terminus location, pink arrows indicate tributary separation, AR=Alsek River, GP=Grand Plateau, PK=Prow Knob, G=Gateway Knob, A=glacier junction, B=tributary separation, C=tributary separation, D=tributary confluence.

Sentinel images from June 2022 illustrating the development of rifting at yellow arrow, that leads to the July 1 calving event. A=glacier junction, B=tributary separation, C=tributary separation