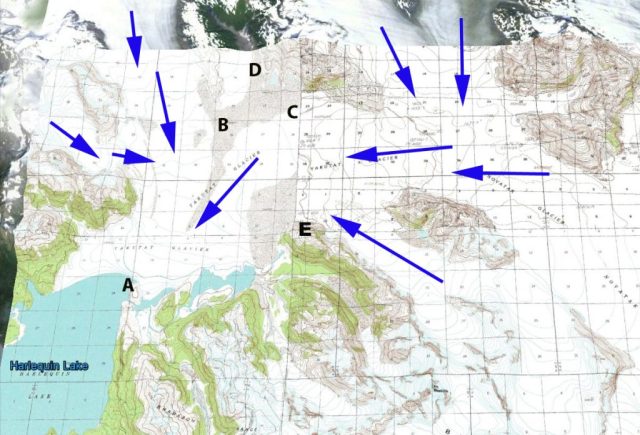

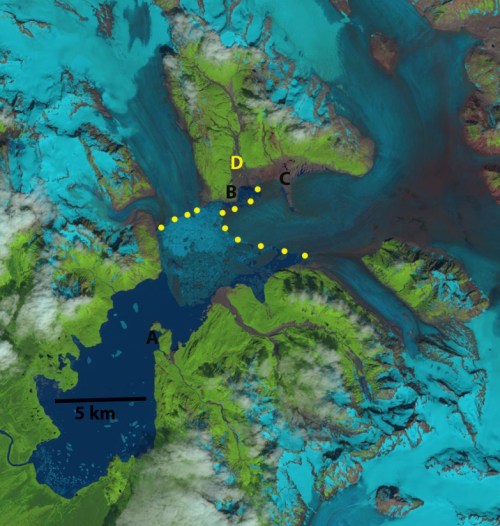

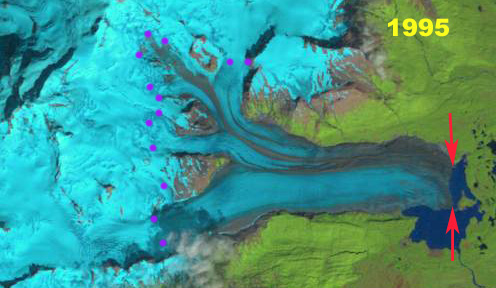

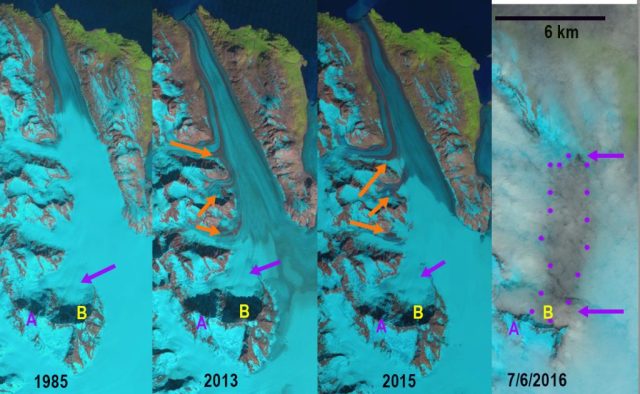

Field Glacier in Landsat images from 1984, 2013 and 2017. The red arrow indicates the 1984 terminus, the yellow arrows the 2013 terminus and the yellow dots the 2017 terminus. The purple arrows indicate developing lateral margin lakes in 2013 and purple dots the transient snowline.

The Field Glacier flows from the northwest side of the Juneau Icefield, and is named for Alaskan glaciologist and American Geographical Society leader William O. Field. Bill also helped initiate the Juneau Icefield Research Program, which Maynard Miller then ably managed for more than 50 years. The JIRP program is still thriving today. In 1981, as a part of JIRP, I had my first experience on this glacier. It was early August and there was new snowfall everyday that week. Jabe Blumenthal, Dan Byrne and myself undertook a ski journey to examine the geology on several of the exposed ridges and peaks, note the burgundy line and X’s on image below. This was truly a remote area. The glacier begins from the high ice region above 1800 meters, there are several icefalls near the snowline at 1350 meters, and then it descends the valley ending at 100 meters. The runoff descends the Lace River into Berners Bay.This post focuses on the significant changes occurring at the front of the Field Glacier. The development of a proglacial lake at the terminus is accelerating and spreading into the main southern tributary of the glacier. In 2013 it was observed that the lake was going to quickly expand and develop a second arm in that valley, as the two main tributaries separate.

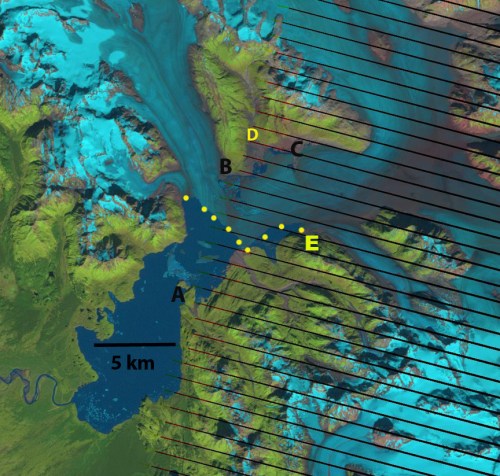

The USGS map from 1948 imagery and the 1984 imagery indicate little change in the terminus position, with only a small lake at the terminus in 1984 with most of the margin resting on the outwash plain. The Field Glacier by 2006 had developed a proglacial lake at the terminus that averaged 1.6 km in length, with the east side being longer. There are several small incipient lakes forming at the margin of the glacier above the main lake, each lake indicated by black and orange arrow. In 2009 the lake had expanded to 2.0 km long and was beginning to incorporate the incipient lake on the west side of the main glacier tongue. There was also a lake on the north side of this tributary. This lake was noted as being poised to soon fill the valley of the south tributary and fully merge with the main, as yet unnamed lake at the terminus, maybe this should be Field Lake. In 2013 Google Earth imagery indicates the fragile nature of the terminus tongue that is about to further disintegrate. From 1984 to 2017 Field Glacier has experienced a retreat of 5300 m of the southern branch and 4050 m of the northern branch. This glacier is experiencing retreat and lake expansion like several other glaciers on the Juneau Icefield, Gilkey Glacier, Eagle Glacier, and Antler Glacier.

Development of proglacial lakes from 2006 to 2009.

Terminus noted for 1984 and 2011 and the snowline in 2011. JIRP camp locations noted by X’s.

2013 Google Earth image of the terminus. Many small icebergs already separating.