Landsat images from Sept. 2015 and Sept. 2016. Red arrow is the 1988 terminus and the yellow arrow the 2016 terminus. I marks an icefall location and point A marks the large iceberg.

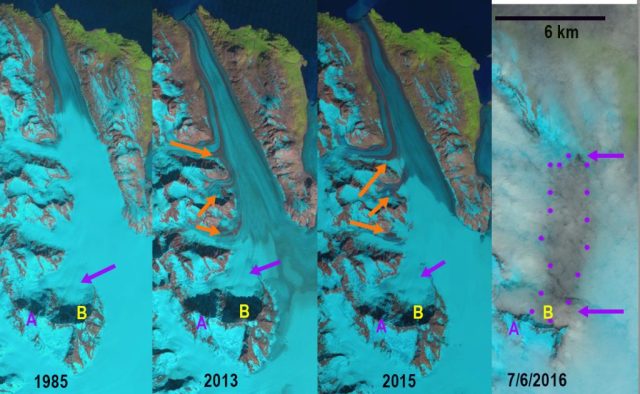

Porcupine Glacier is a 20 km long outlet glacier of an icefield in the Hoodoo Mountains of Northern British Columbia that terminates in an expanding proglacial lake. During 2016 the glacier had a 1.2 square kilometer iceberg break off, leading to a retreat of 1.7 km in one year. This is an unusually large iceberg to calve off in a proglacial lake, the largest I have ever seen in British Columbia or Alaska. NASA has generated better imagery to illustrate my observations. Bolch et al (2010) noted a reduction of 0.3% per year in glacier area in the Northern Coast Mountains of British Columbia from 1985 to 2005. Scheifer et al (2007) noted an annual thinning rate of 0.8 meters/year from 1985-1999. Here we examine the rapid retreat of Porcupine Glacier and the expansion of the lake it ends in from 1988-2016 using Landsat images from 1988, 1999, 2011, 2015 and 2016. Below is a Google Earth view of the glacier with arrows indicating the flow paths of the Porcupine Glacier. The second images is a map of the region from 1980 indicates a small marginal lake at the terminus.

Landsat images from 1988 and 2016 comparing terminus locations and snowline. Red arrow is the 1985 terminus and the yellow arrow the 2016 terminus. I marks an icefall location and point A marks the large iceberg. Purple dots indicate the snowline.

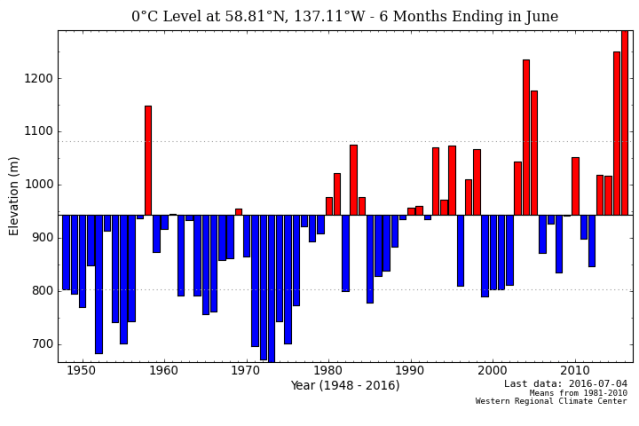

In 1988 a tongue of the glacier in the center of the lake reached to within 1.5 km of the far shore of the lake, red arrow. The yellow arrow indicates the 2016 terminus position. By 1999 there was only a narrow tongue reaching into the wider proglacial lake formed by the juncture of two tributaries. In 2011 this tongue had collapsed. In 2015 the glacier had retreated 3.1 km from the 1988 location. In the next 12 months Porcupine Glacier calved a 1.2 square kilometer iceberg and retreated 1.7 km, detailed view of iceberg below. The base of the icefall indicates the likely limit of this lake basin. At that point the retreat rate will decline.The number of icebergs in the lake at the terminus indicates the retreat is mainly due to calving icebergs. Glacier thinning of the glacier tongue has led to enhanced calving. The retreat of this glacier is similar to a number of other glaciers in the area Great Glacier, Chickamin Glacier, South Sawyer Glacier and Bromley Glacier. The retreat is driven by an increase in snowline/equilibrium line elevations which in 2016 is at 1700 m, similar to that on South Sawyer Glacier in 2016.

August 27, 2016 Sentinel 2 image of iceberg red dots calved from front of Porcupine Glacier.

Canadian Toporama map of Porcupine Glacier terminus area in 1980.

Google Earth view indicating flow of Porcupine glacier.

1999 Landsat image above and 2011 Landsat image below indicating expansion of the lake. Red arrows indicate the snowline. Purple, orange and yellow arrows indicate the same location in each image.