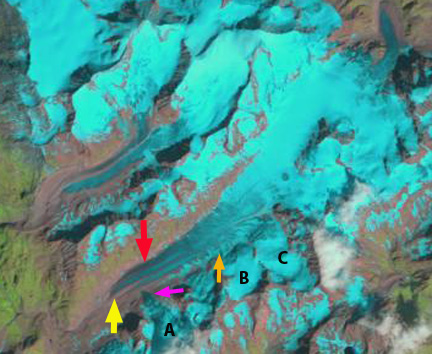

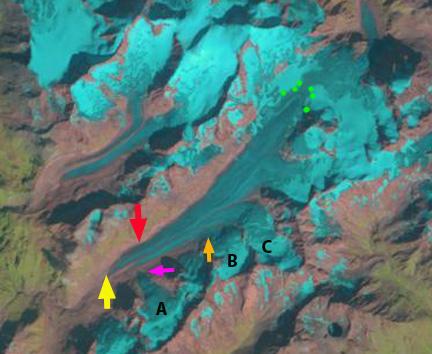

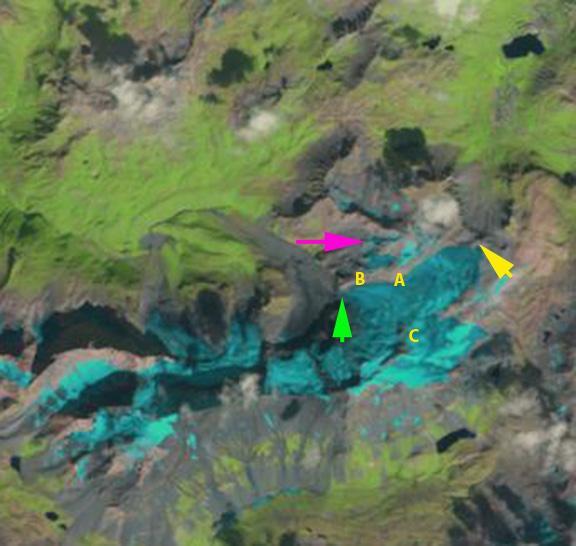

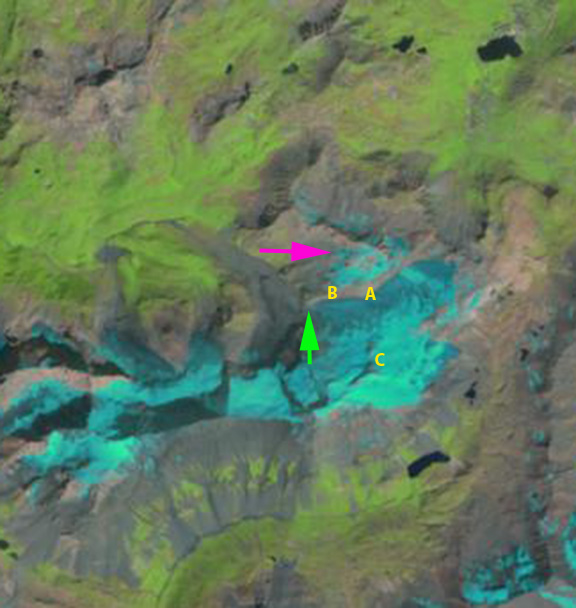

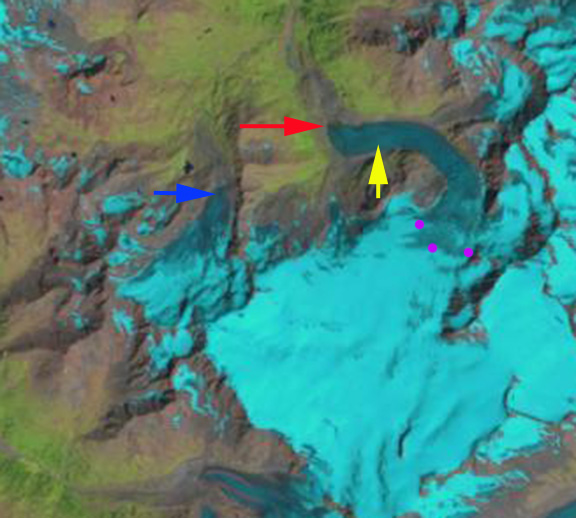

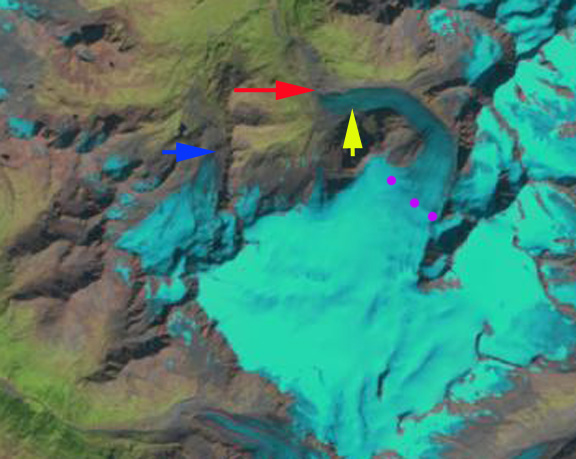

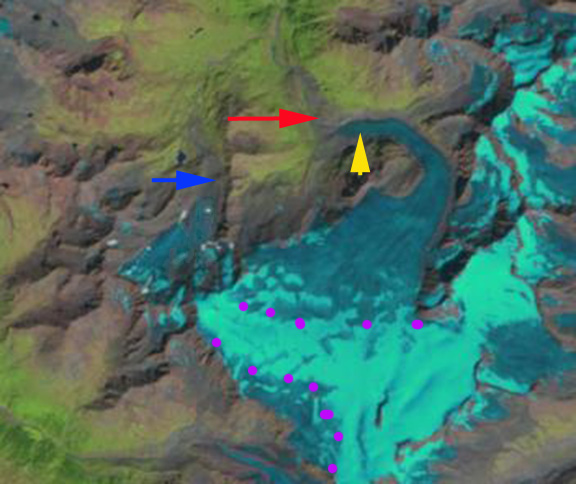

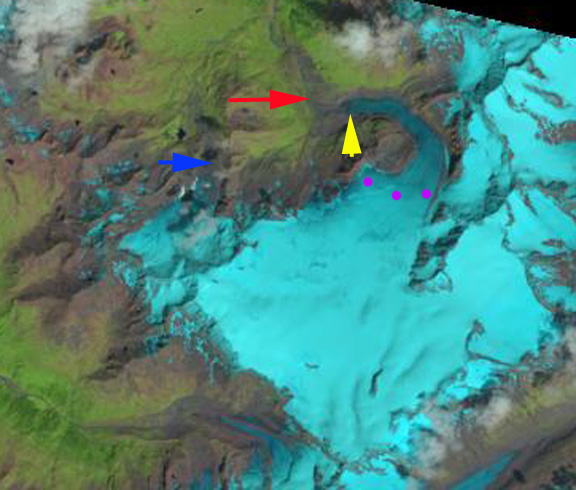

Landsat Image based Watson River discharge sequence June 14-July 8, 2015

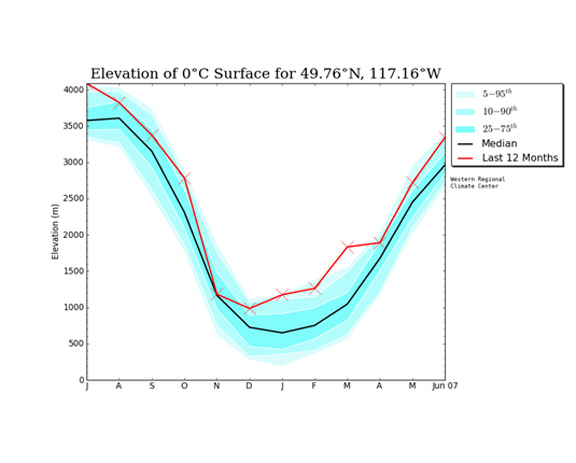

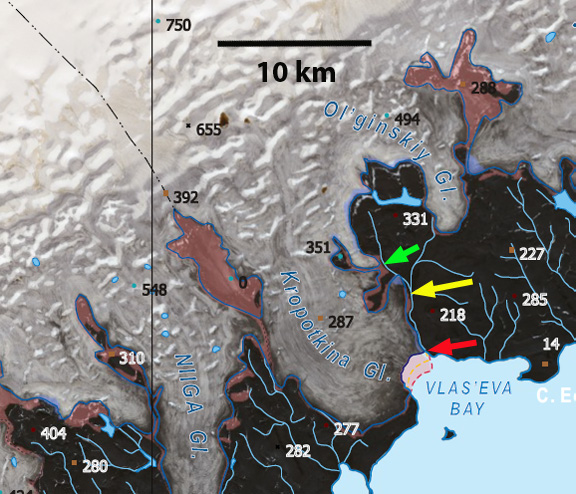

It was 30 years ago I first participated in Greenland Ice Sheet research, there was not much of it at the time. However, there was the recognition of the importance for sea level rise with global warming, and this was driving an increase in research at that time. The level of research has increased exponentially in the last decade. One long standing and remarkable program that indicates the long term thinking that has helped us develop an understanding of ice sheet changes, is the K-Transect of ablation stakes emplaced in the Russell Glacier Catchment. Here we examine the changing snowline from Mid-June to early July of 2015, as well as the longer term record. The Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research Utrecht has maintained the best long term field based ablation record on the GIS, the K-Transect. This resulted in van de Wal et al., (2012) reporting on 21 years of surface mass balance in the region. At one site, S9 (1520 m) near the equilibrium line altitude (ELA), the long term record indicates a rise in the ELA in recent years, see figure below, and a more negative surface mass balance. This record has also been crucial in helping to build surface mass balance models for the GIS. The results updated daily from one such model, is at the Polar Portal, maintatined by the DMI – Danish Meteorological Institute, GEUS – The Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland and DTU Space – National Space Institute. This summer the Automatic Weather Station on this transect Kan M, at 1270 m did not experience temperatures above 0 C until June 19th and they have been consistently above that since, (PROMICE, 2015). At S9 temperatures have been reaching 4 C most days in July (IMAU, 2015).

So Thank You to PROMICE, Polar Portal, IMAU, NASA and others for the remarkable progress and sharing of data.

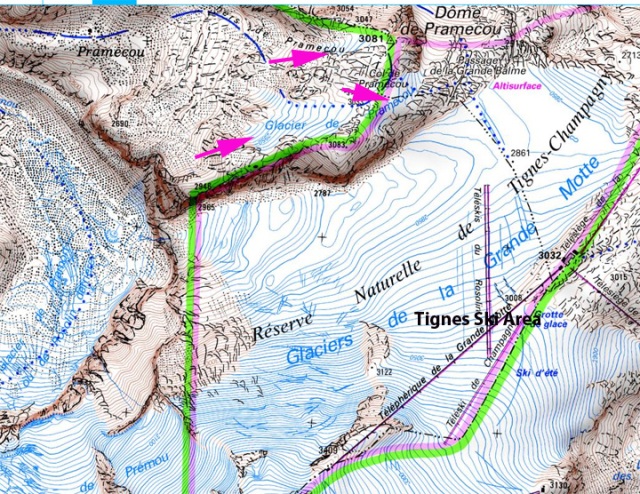

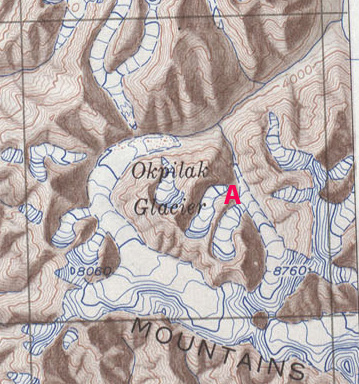

K-Transect map from van As et al (2012)

Surface mass balance at S9 on the K-Transect from van de Wal (2012).

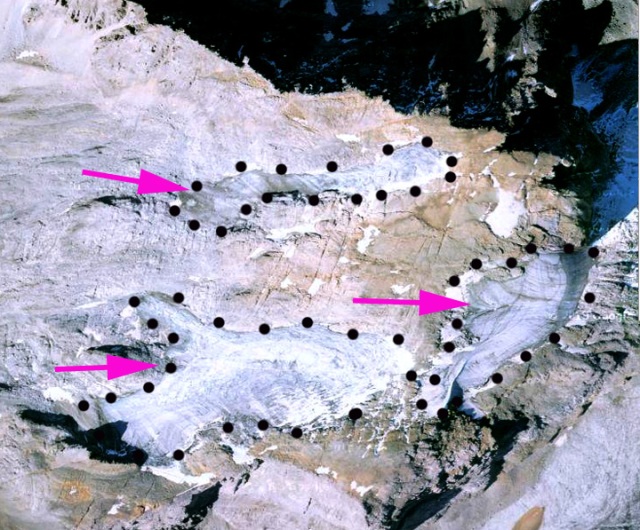

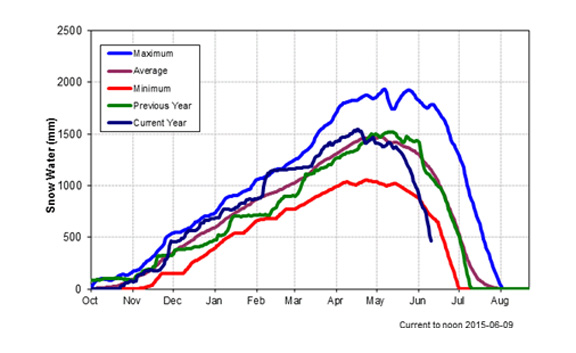

Supraglacial lakes were mapped in detail for the period by Fitzpatrick et al (2014), who found the lakes were forming several weeks earlier in 2010-2012 and at higher elevations than before. They also observed as seen in graph below that Watson River except for in 2010 had a distinct rise in flow in mid-July. Notice the lag between initial melt that fills lakes, volume loss shown, and the rise in Watson River.

Watson River discharge and lake volume loss in K-Transect region from Fitzpatrick et al (2014)

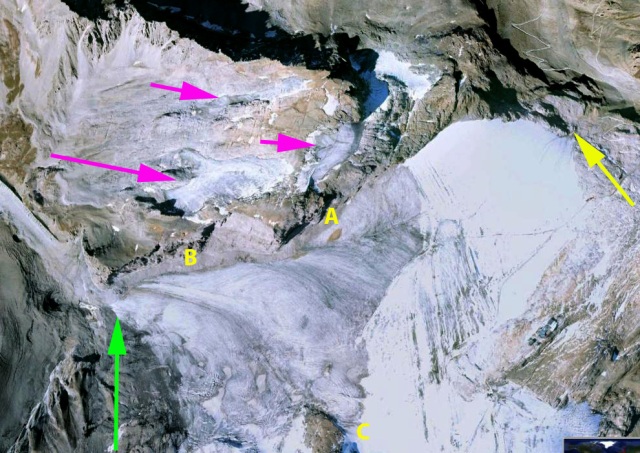

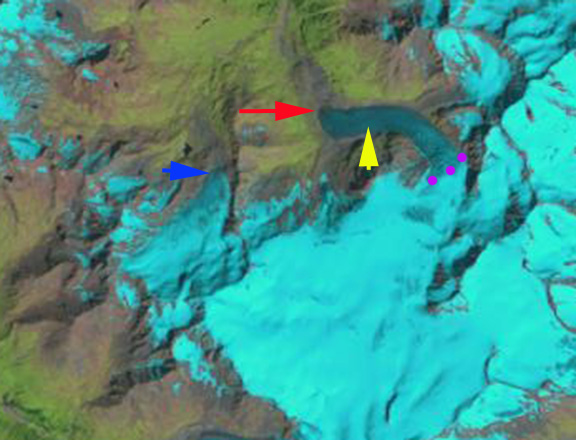

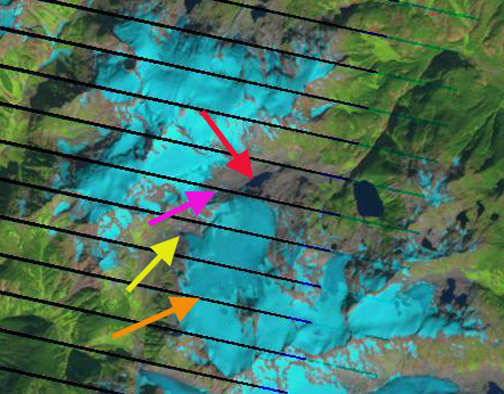

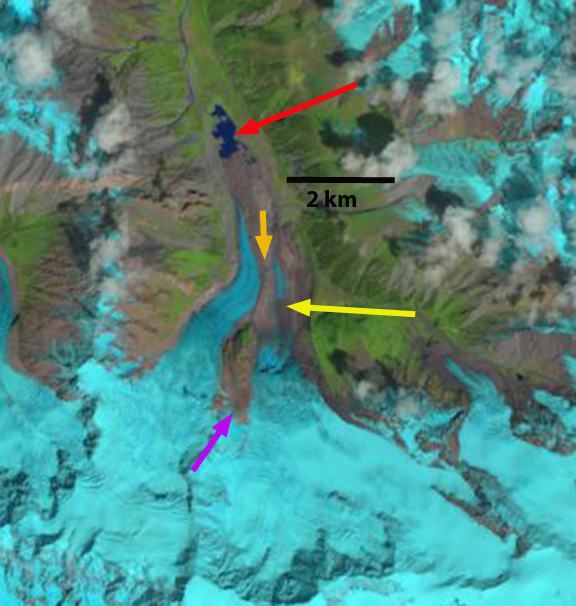

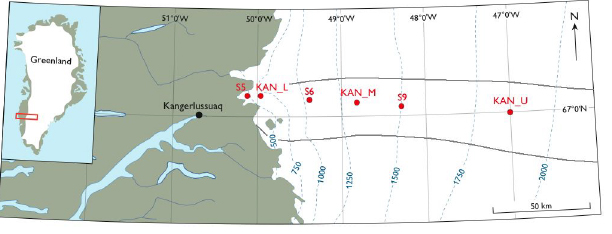

This all played out in the last few weeks. The melt season was off to a slow start in 2015 as indicated both by the Polar Portal and Landsat imagery, note on June 14th that lakes beyond the GIS had ice cover still, the snowline was at 750 m, blue dots, with spotty snow patches below this. The lack of melt in also evident in the lack of supraglacial lakes. Note the lack of discharge in Watson River, pink arrow. By June 29th melt had begun in earnest with the snowline moving inland 25 kilometers and rising to 1150 m. Discharge was greater, but still limited in Watson River. The main belt of supraglacial lakes, red arrow was at m. By July 8th, the snowline had moved more than 50 km inland since June 14th to an altitude of 1450 m. This is close to S9. The snowline is not the ELA on the GIS as there are zones of superimposed ice below the snowline. However, with the transient snowline this high in early July, the ELA will inevitably be higher than S9 at 1520 m. The discharge in Watson River will continue to rise and become more variable as the glacial hydorologic system matures van As et al (2012). This post will be updated with imagery from later in the 2015 ablation season.

Surface Mass Balance from model data

June 29, 2015 Landsat Image

<a href="http:/

July 8, 2015 Landsat Image

July 8, 2015 Landsat Image

Google Earth image showing late summer discharge of Watson RIver.