Fording the outlet of Blanca Lake, headwater North Fork Skykomish River.

The focus this spring has been on the developing drought in Washington as a result of record low snowpack, the winter was a record warmth though not dry. The focus of this article is on another component of many alpine watersheds, glacier runoff, both the ameliorating role and their reduced ability as they shrink to augment flow during low flow periods. Glaciers act as natural reservoirs storing water in a frozen state instead of behind a dam. Glaciers modify streamflow releasing the most runoff during the warmest, driest periods of summer, when all other sources of water are at a minimum. Annual glacier runoff is highest in warm, dry summers and lowest during wet, cool summers. This is the first of two posts looking at the response of specific alpine watersheds to glacier change and glacier runoff, the second will look at the Nooksack River.

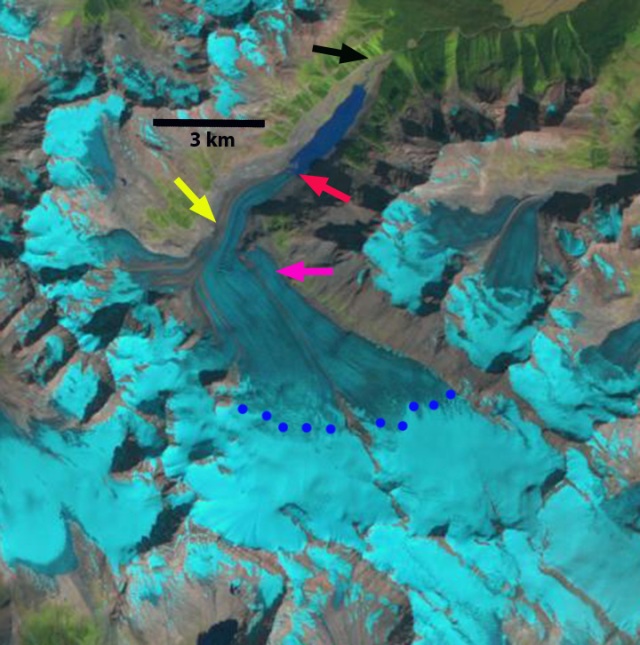

Watersheds in mountainous Pacific Northwest are comprised of pluvial, nival and glacial segments. The pluvial segments have peak flows in the winter due to the winter storm events (Dery et al., 2009). Nival streams peak in the May and June with the high snowmelt, and glacially fed streams peak in July and August during peak glacier melt (Pelto, 2008; Dery et al., 2009). The loss of glaciers from a watershed then reduces streamflow primarily during minimum flow periods The amount of glacier runoff is the product of surface area and ablation rate. The glacier retreat and loss of glacier runoff has been quite pronounced in the Skykomish River Basin, North Cascades, Washington from 1950-2014 (Pelto, 2011). This summer we will return to make observations on 4 glaciers in this watershed for the 32nd consecutive year. We will be measuring flow with the Nooksack Indian Tribe again this year below glaciers, and we will observe the drought impact on the glaciers and downstream.

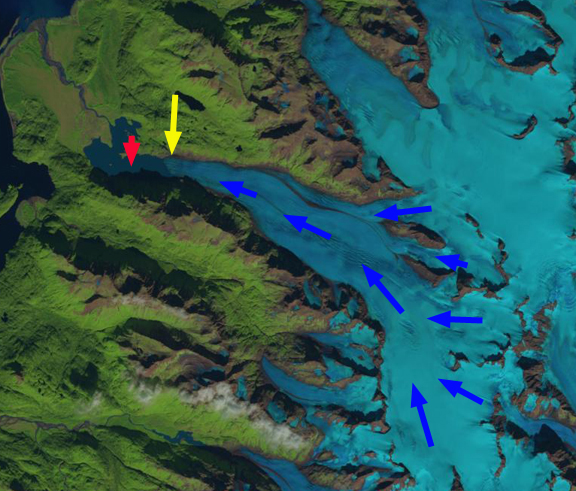

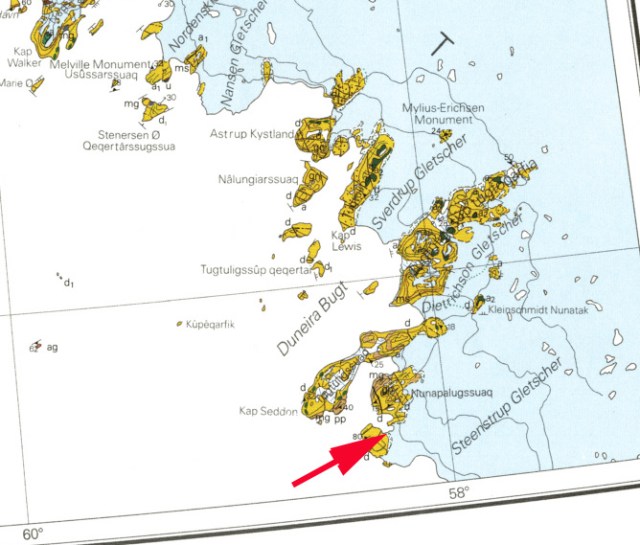

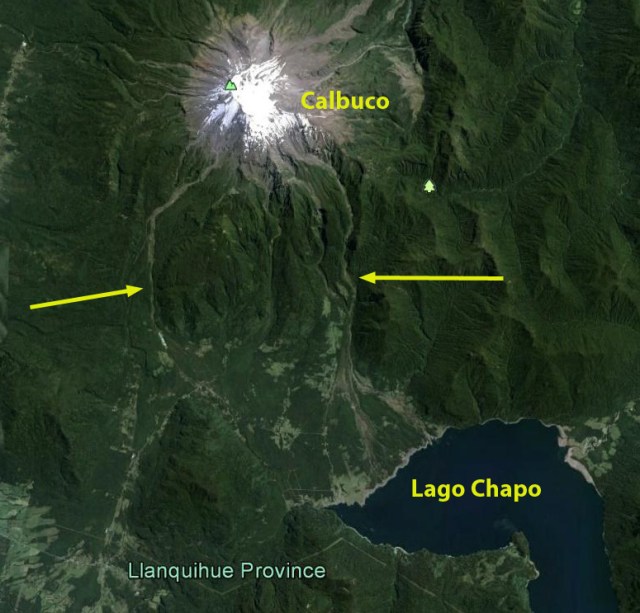

Skykomish Basin Map-Light blue arrows indicate the four main glaciers: 1=Columbia, 2=Hinman, 3=Foss, 4=Lynch

An analysis comparing USGS streamflow records for the Skykomish River at Gold Bar for the 1950-1985 to the 1985-2009 period indicates that during the recent period the Skykomish River summer streamflow (July-September) has declined 26% in the watershed, spring runoff (April-June) has declined 6%, while winter runoff (November-March) has increased 10% (Figure 1). The reduction of the glacial melt component augmenting summer low flows is already resulting in more low-flow days in the North Cascade region. In the Skykomish River watershed from 1958-2009 glacier area declined from 3.8 km2 to 2.1 km2, a 45% decline (Pelto, 2011). Columbia, Foss, Hinman and Lynch Glacier, the primary glaciers in the basin, declined in area by 10%, 60%, 90% and 35% respectively since 1958. Annual mass balance measurements completed from 1984-2009 on Columbia, Foss and Lynch Glacier indicate a mass loss of 13.1 m w.e. Despite 15% higher ablation rates during the 1985-2009 period, the 45% reduction in glacier area led to a 38% reduction glacier runoff between 1958 and 2009. This means less glacier runoff in late summer.

Change in seasonal discharge in the Skykomish River. Increase in winter, decrease in summer.

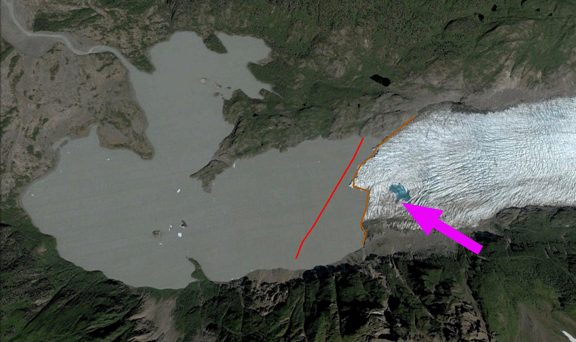

Lynch glacier Retreat

Hinman Glacier, view from former terminus

Columbia Glacier losing its snowcover in the accumulation zone.

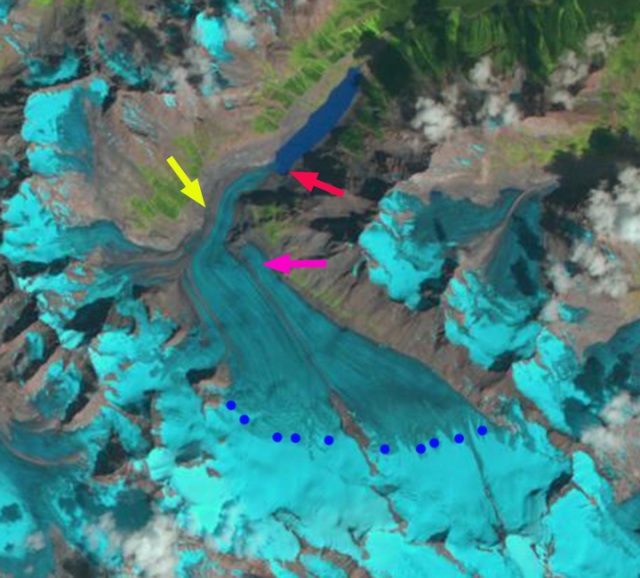

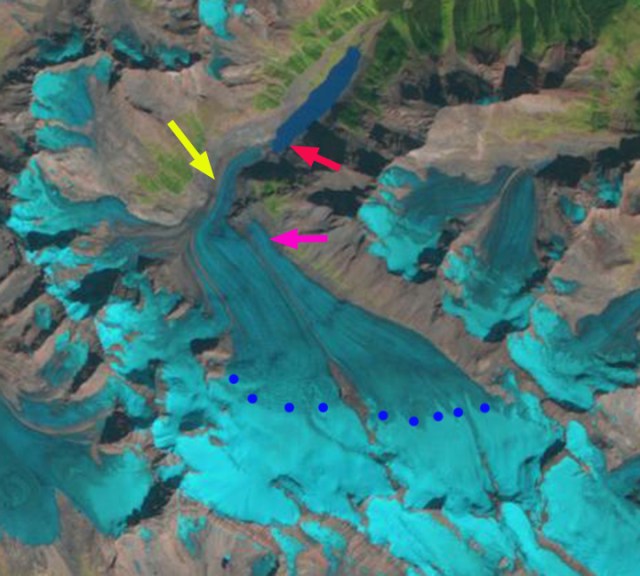

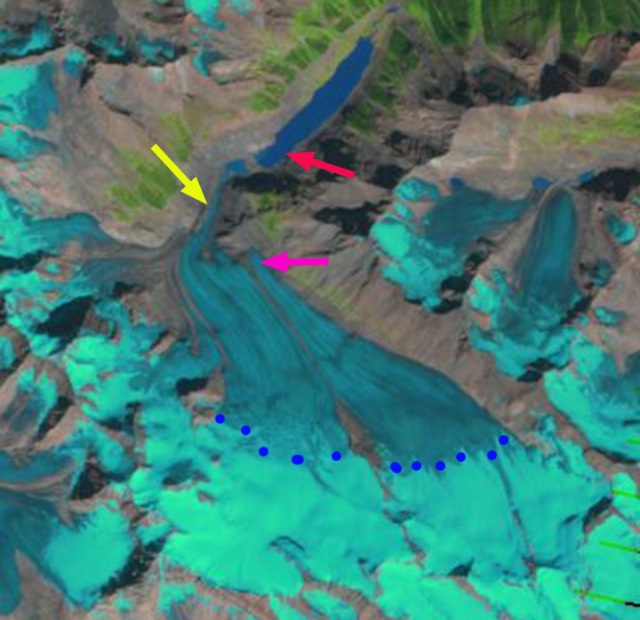

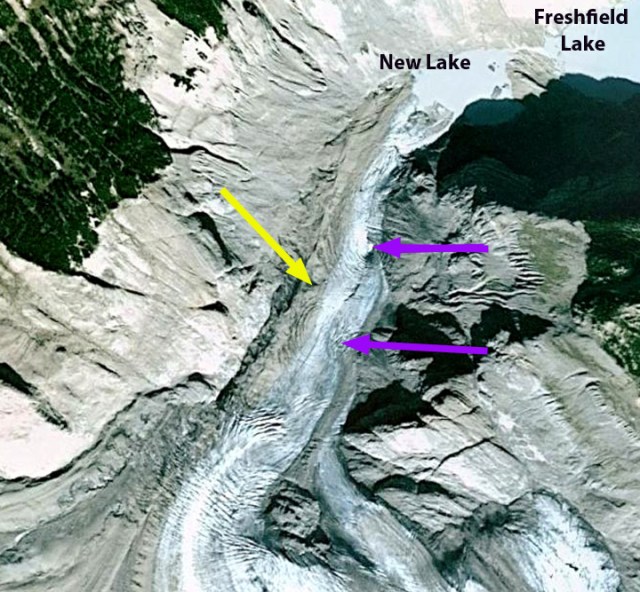

Columbia Glacier Retreat. Detailed report.

A key threshold of in-stream flow levels considered insufficient to maintain short term survival of fish stocks is below 10% of the mean annual flow (Tennant, 1976). For the Skykomish River 10% of mean annual flow is 14 m3s-1. In the Skykomish River from 1950-2013 there have been 230 melt season days with discharge below 14 m3s-1. Of these 228, or 99% of the low flow days, have occurred since 1985. The loss of 30-40% of the glacier runoff is a key reason for the onset of critical low flow days. Of more concern for aquatic life is the occurrence of extended periods of low flow (Tennant, 1976). From 1929-2009 in the Skykomish River basin there have been eight years where streamflow dropped below 14 m3s-1 for 10 consecutive days during the melt season, 1986, 1987, 1992, 1998, 2003, 2005, 2006 and 2007. It is likely that 2015 will join this list.

Number of days when flow fell below 10% of the long term mean annual flow. Only one day from 1950 to 1985 met this criteria. Precipitation has not declined substantially during this interval, hence earlier snowmelt, reduced glacier runoff and greater evapotranspiration must be causing the increase in late summer low flow periods. The 38% reduction in glacier runoff did not lead to a significant decline in the percentage summer runoff contributed by glaciers under average conditions; the contribution has remained in the range of 1-3% from July-September. The glacier runoff decline impacted river discharge only during low flow periods in August and September. In August, 2003 and 2005 glacier ablation contributed 1.5-1.6 m3s-1 to total discharge, or 10-11% of August discharge. While declining glacier area in the region has and will lead to reduced glacier runoff and reduced late summer streamflow, it has limited impact on the Skykomish River except during periods of critically low flow, below 14 m3s-1 when glaciers currently contribute more than 10% of the streamflow.

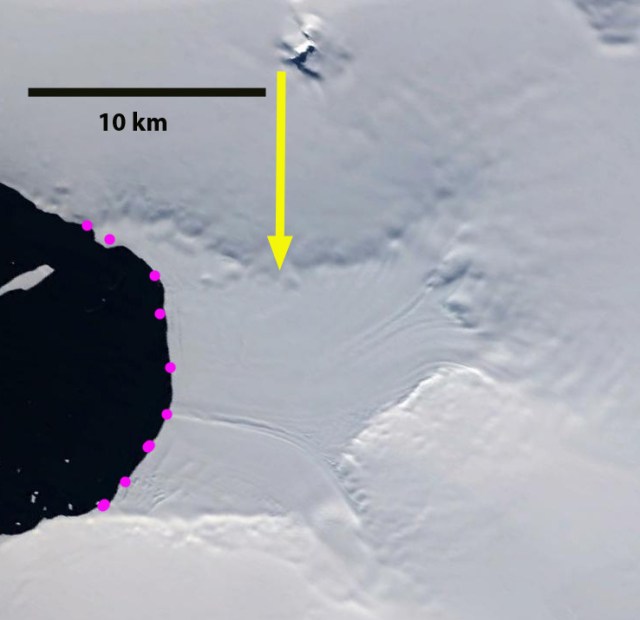

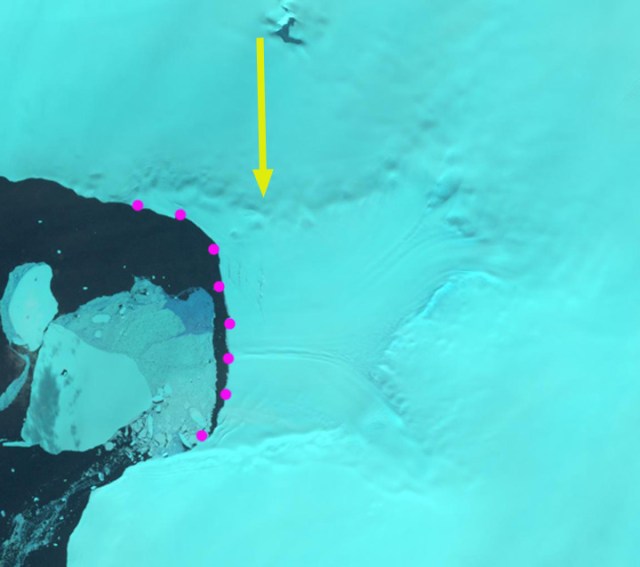

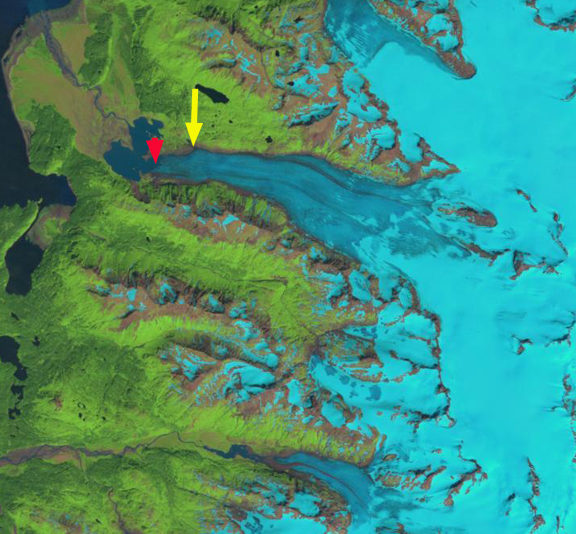

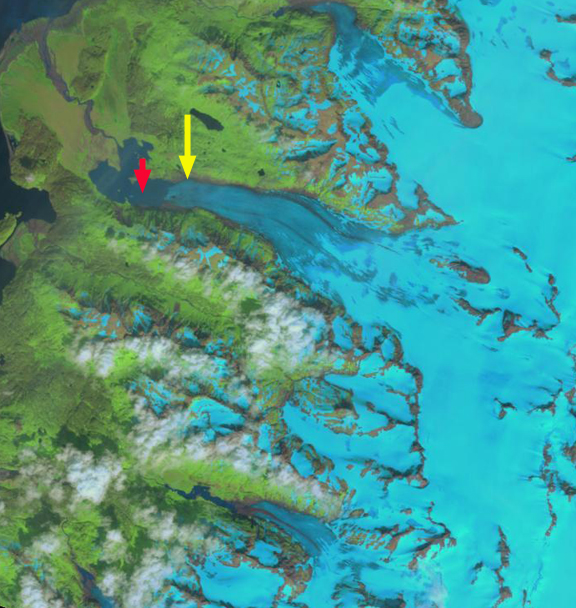

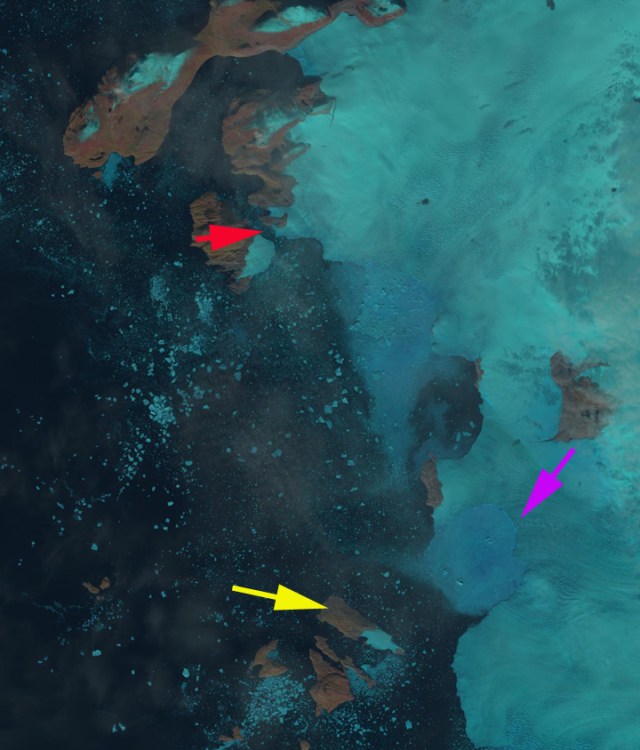

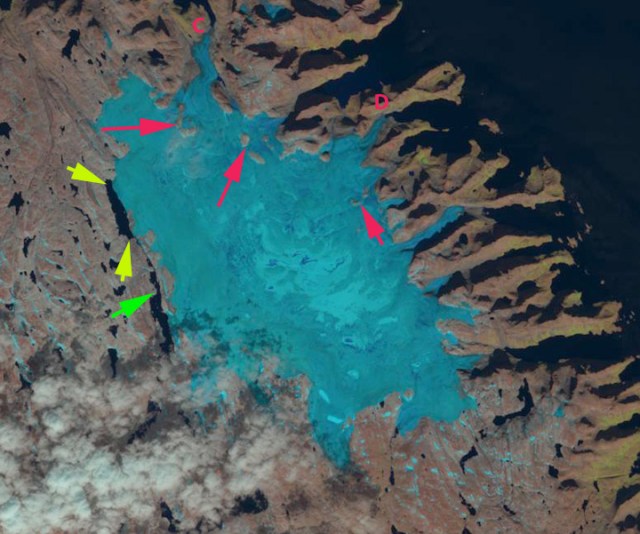

For 2015 the lack of snowpack in the Skykomish Basin is evident from a comparison of images from April 20th 2015 and June 4th, 2014. Snowpack during 2014, an average winter, was higher in mid-June than in mid-April in 2015. Arrows in each side by side are in same location. This indicates that the pluvial and nival segment of flow to the Skykomish River will be at a minimum late this summer. Currently flow at the USGS gage in Gold Bar is 28% of normal at 2050 CFS, which is an all time low for the record that begins in 1929, previous low in 1977 at 2755 CFS. The river has not reached 2750 CFS the entire month of May. Glacier flow has continued to decline with area extent losses. This combination makes it likely, that the Skykomish River will have an extended period of low flow this summer and into the fall. If the summer is drier than average, flows will likely reach a new minimum.

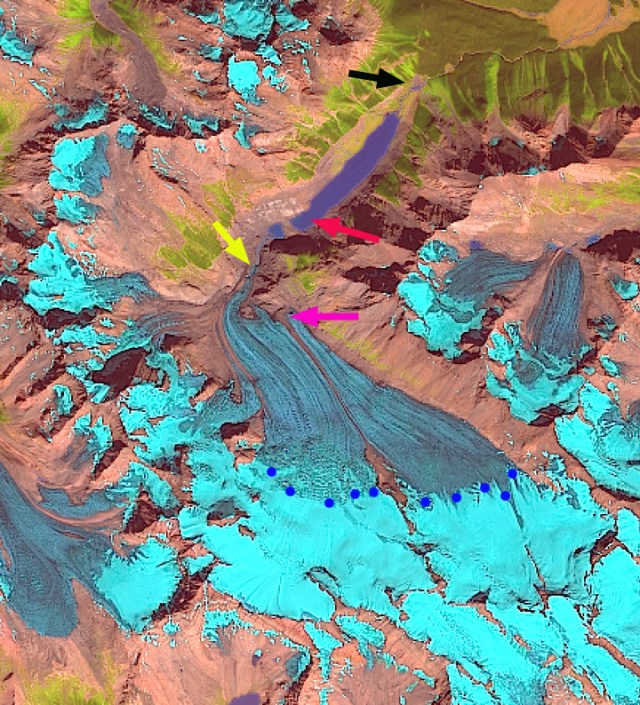

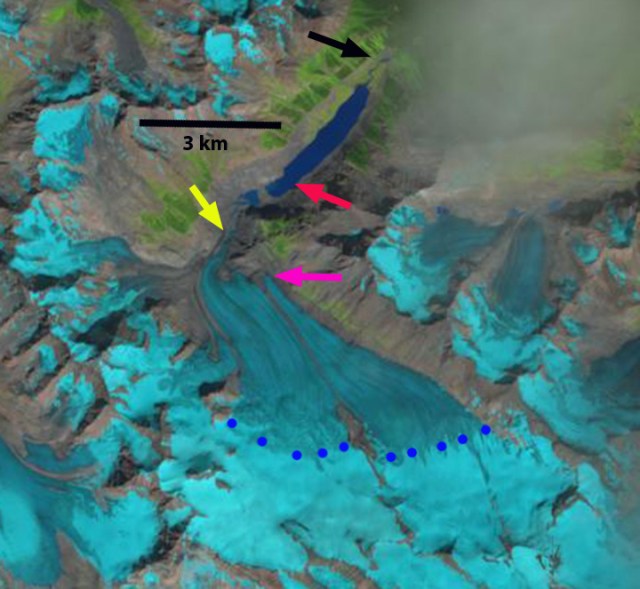

Snowpack comparison in the area of the North Fork Skykomish near Columbia Glacier (C) in April 2015 compared to a snowier June, 2014.

Snowpack comparison in the area of the South Fork Skykomish near Lynch Glacier (D) in April 2015 compared to a snowier June, 2014.

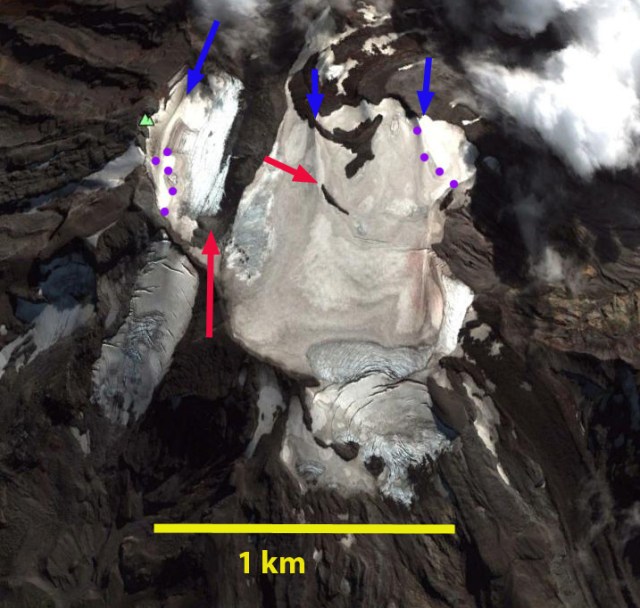

Terminus image of Columbia Glacier in March 2015 (below) with less overall snow than in the image above from August, 2013. (picture below from Rowan Stewart)

Clearly the area will still be beautiful and we will gain two new alpine lakes with the loss of the glacier. After making over 200 measurements in 2010 we completed a mass balance map of the glacier as we do each year. This summer we will be back again for the 32nd annual checkup. There will be likely be record low snowpack, comparable to 2005 the worst year from 1984-2014.

Clearly the area will still be beautiful and we will gain two new alpine lakes with the loss of the glacier. After making over 200 measurements in 2010 we completed a mass balance map of the glacier as we do each year. This summer we will be back again for the 32nd annual checkup. There will be likely be record low snowpack, comparable to 2005 the worst year from 1984-2014.