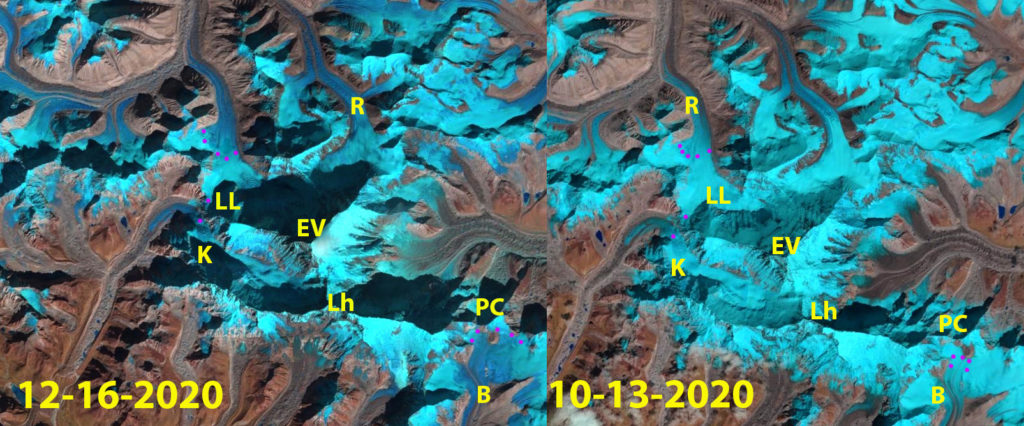

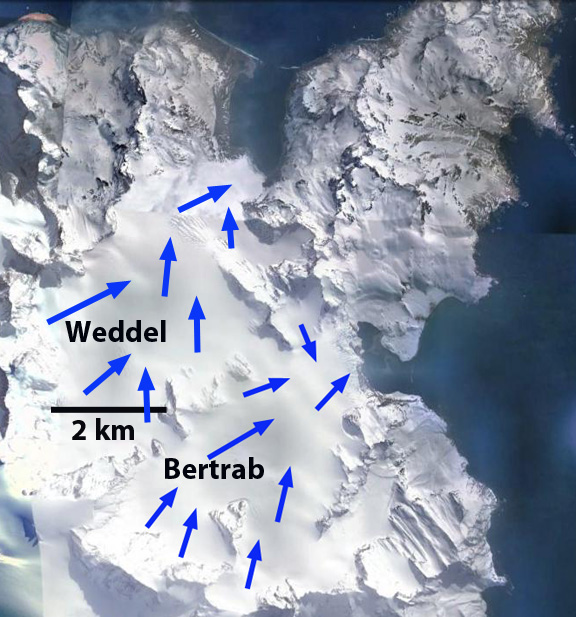

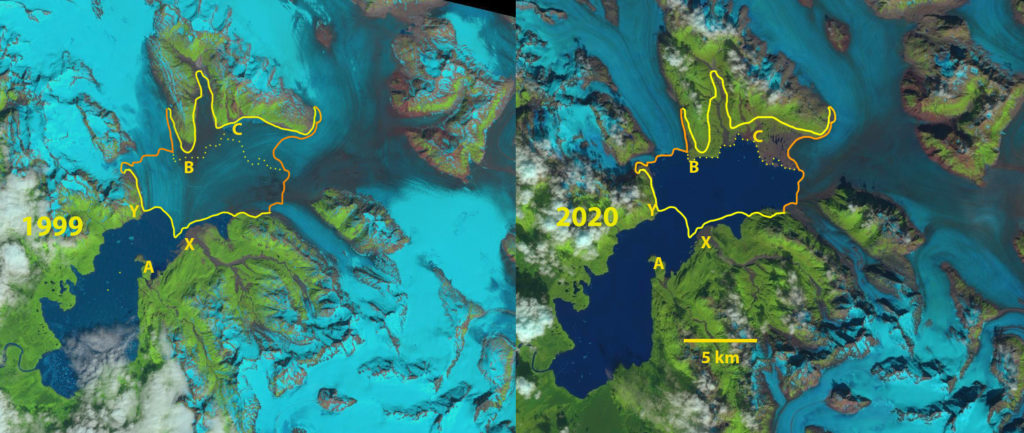

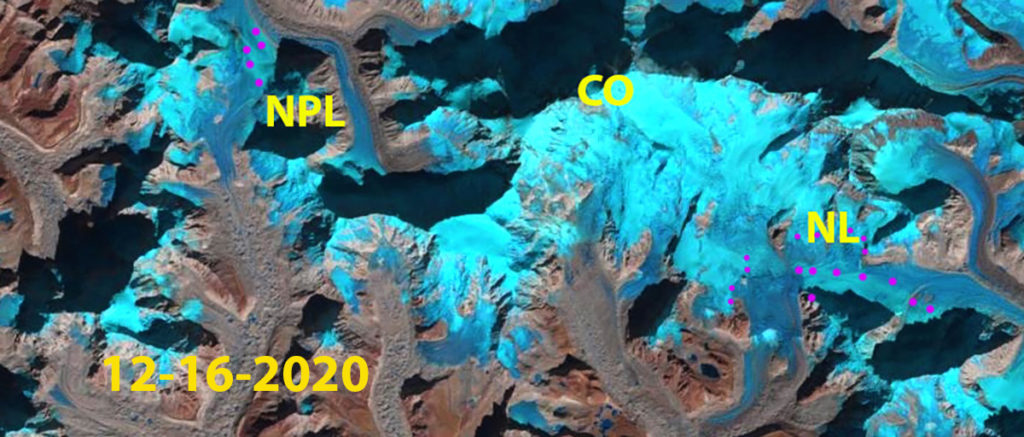

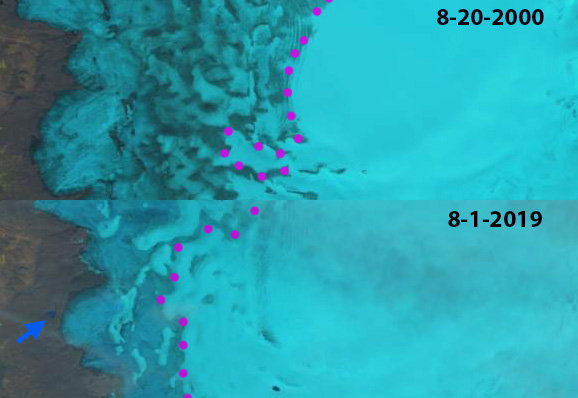

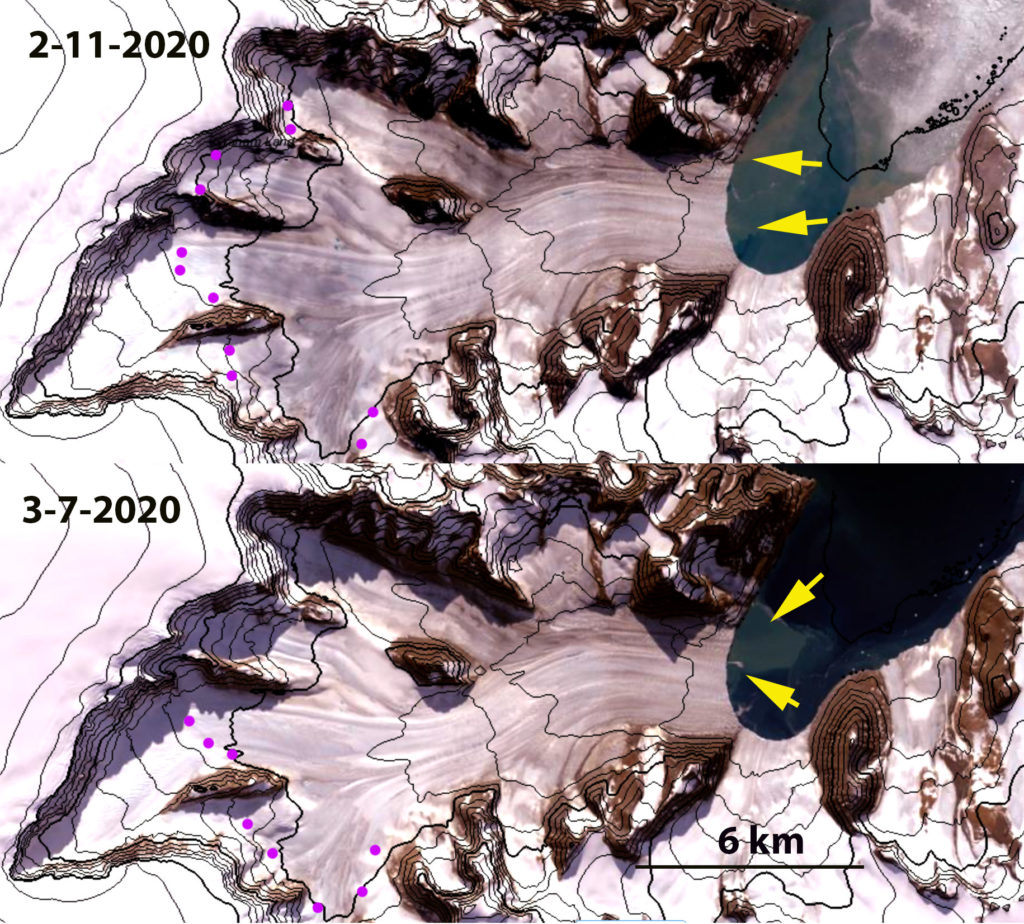

Nangpa La (NPL) and Nup La (NL) in Landsat images from 10-13-2020 and 12-16-2020, CO=Cho Oyu Peak and purple dots indicate the snowline. Both passes can be crossed without traversing snow on December 16.

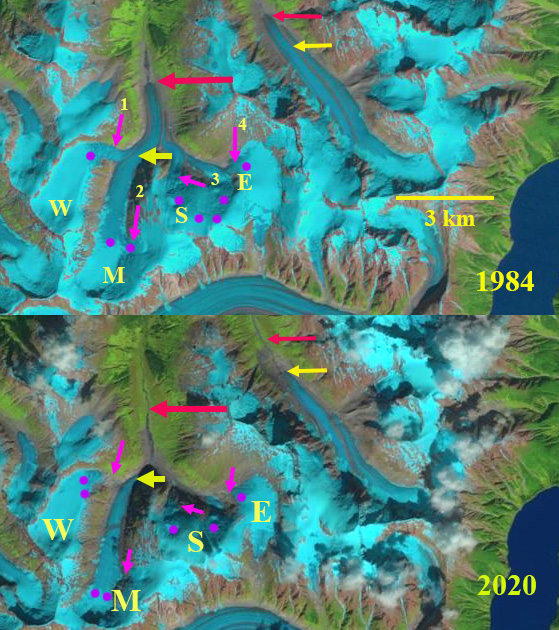

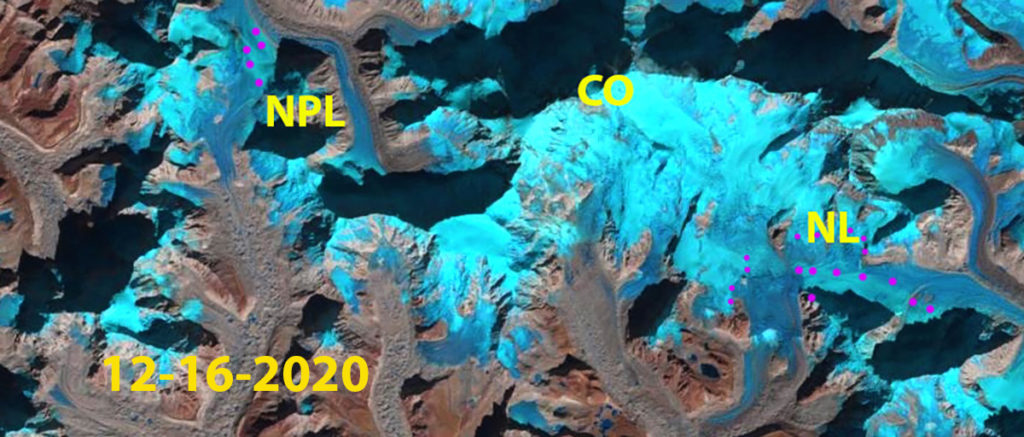

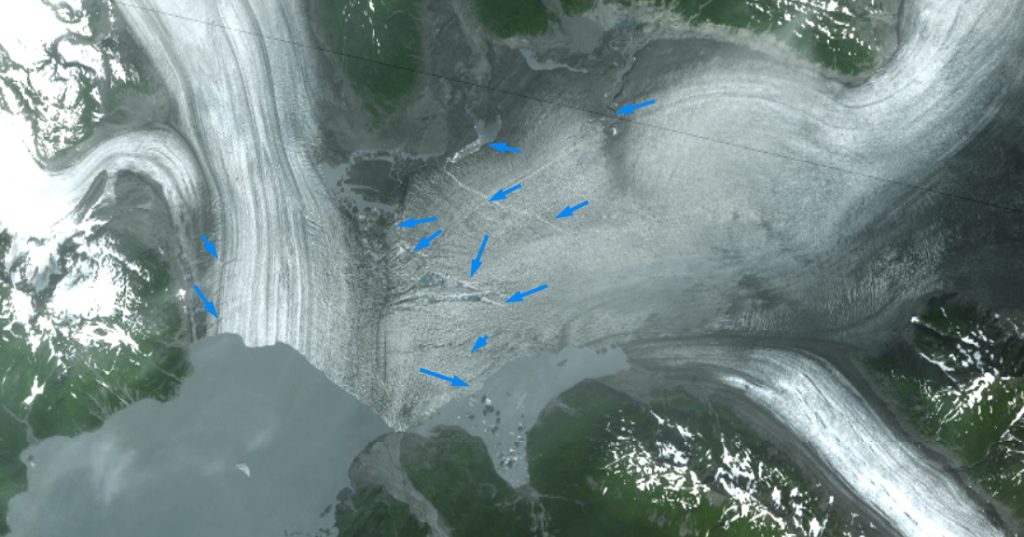

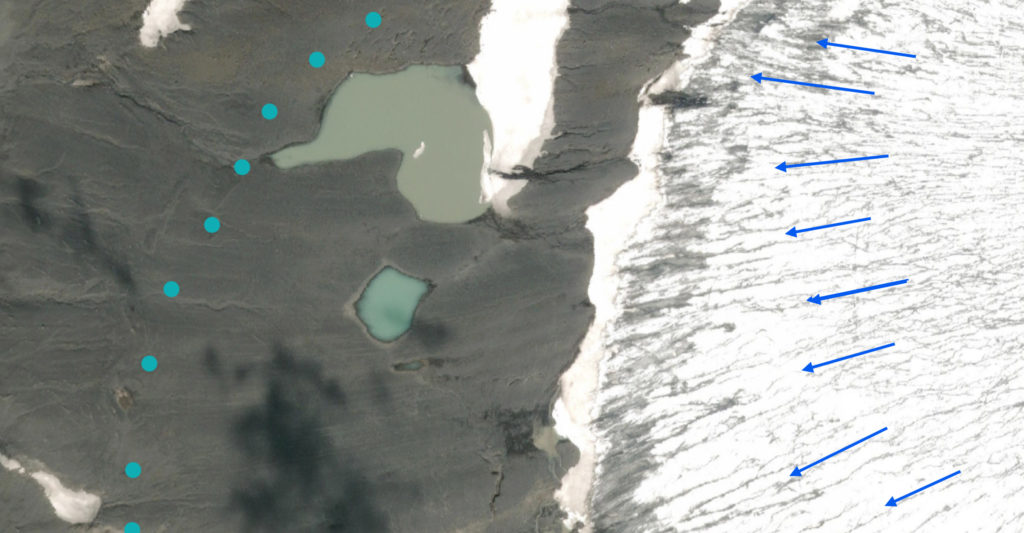

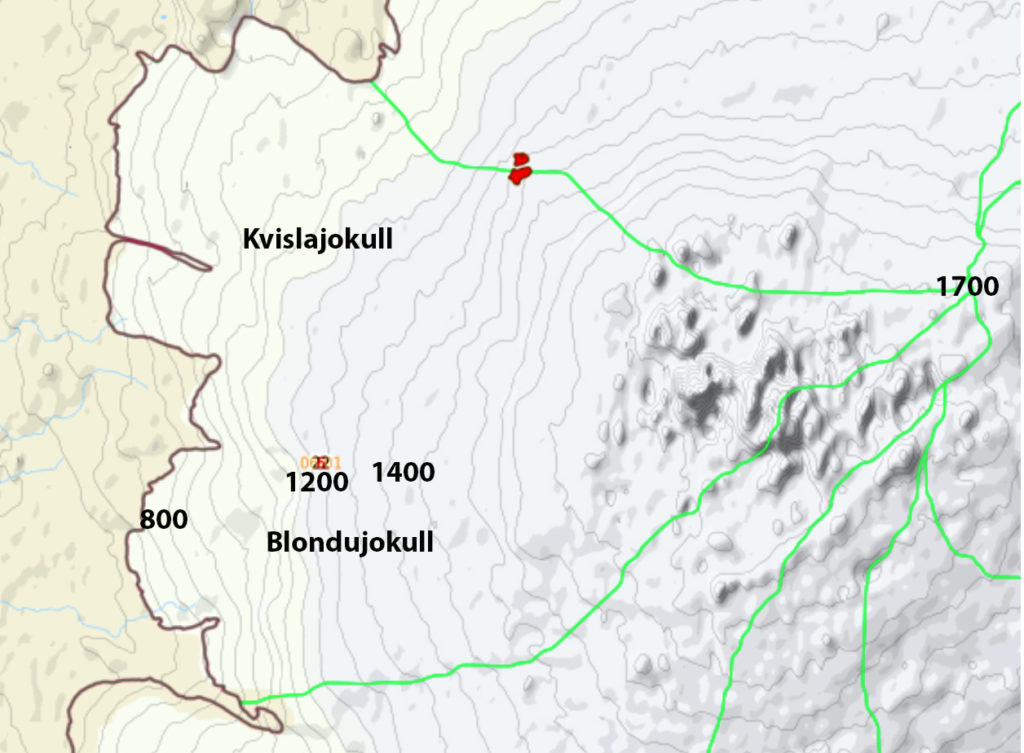

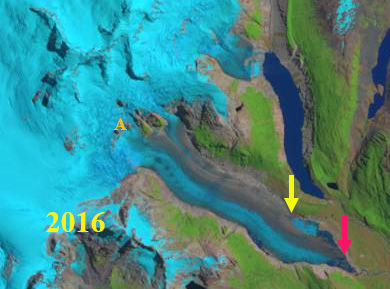

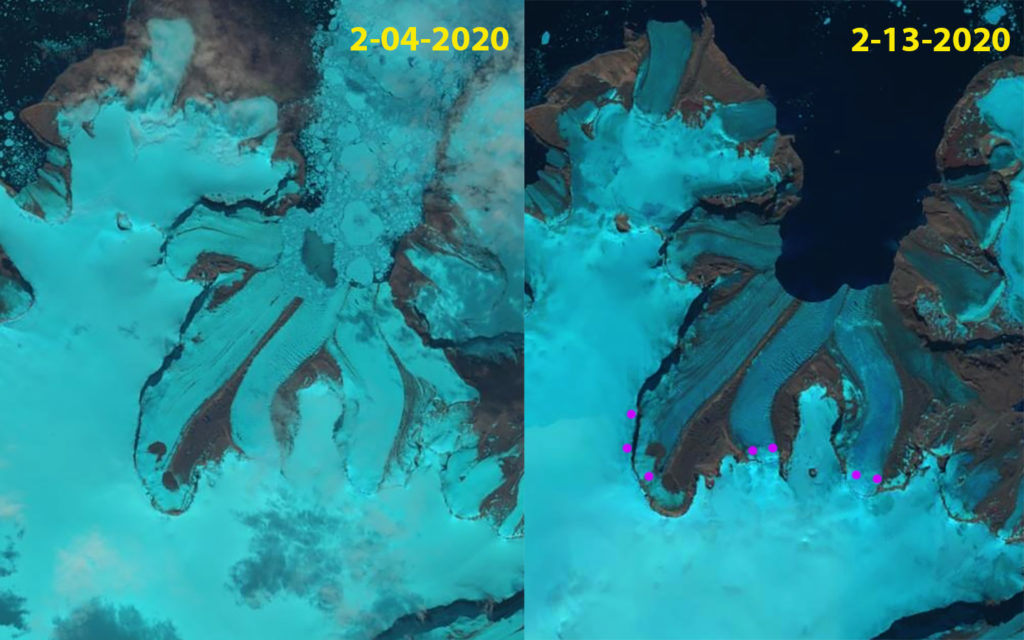

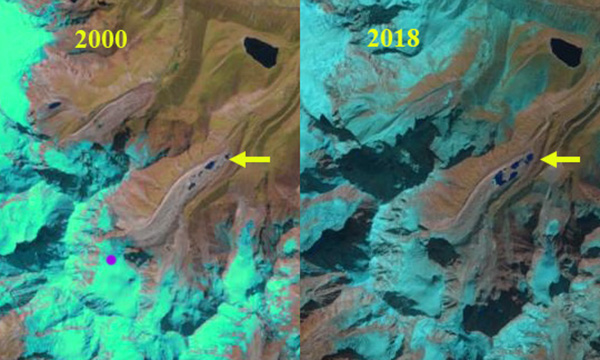

The winter monsoon for the Nepal Himalaya is a dry cold period with limited precipitation or new snow accumulation. Mount Everest region glaciers are summer accumulation type glaciers with ~75% of annual precipitation occurring during the summer monsoon (Wagnon et al 2013; Baker Perry et al 2020). The summer monsoon also is the period of the highest melt rates lower on the glaciers. October has been considered the end of the melt season in the region with little precipitation early in the Post Monsoon and early winter season (October-December), averaging ~3% of the total annual precipitation (Baker Perry et al 2020). The limited snowpack with warmer winter temperatures have led to higher snowlines during the first few months of the winter season in recent years (Pelto, 2019). Here we use a combination of Landsat images from Oct. 13 and Dec 16. to indicate the snowline rise in the vicinity of four high passes between Nepal and China (Tibet) along with The Rolex-National Geographic Perpetual Planet Expedition real time weather data, which for Dec. 16 indicate clear dry, low humidity conditions on Mount Everest, see image below.local weather records. The four passes are Nangpa La (NPL) at the glacier divide between Gyarbarg and Bohte Koshi Glacier, Nup La (NL) at the glacier divide of Ngozumpa and Rongbuk Glacier, Lho La (LL) on a ridge between Rongbuk and Khumbu Glacier and Pethangtse Col (PC) at the top of Barun Glacier. Nangpa La is the only pass that is gentle enough that it can be crossed without mountaineering experience and has been used as a trading route across the Himalaya. Further information at NASA Earth Observatory and paper published by Pelto et al 2021.

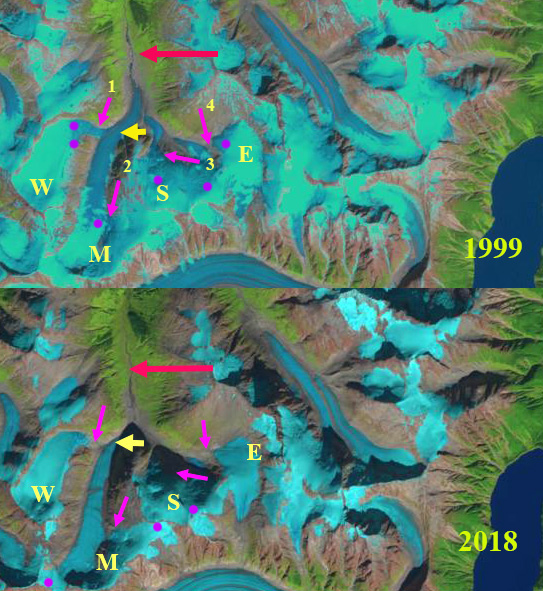

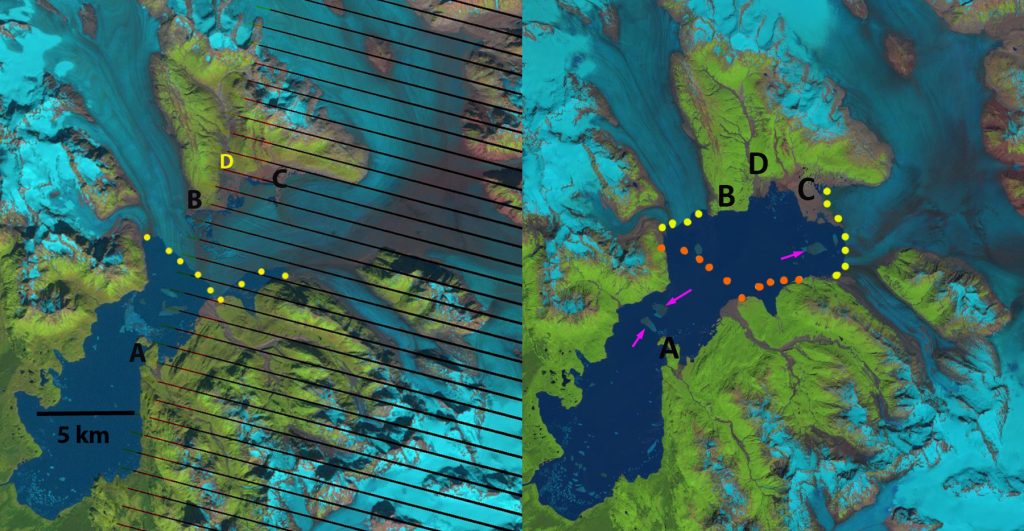

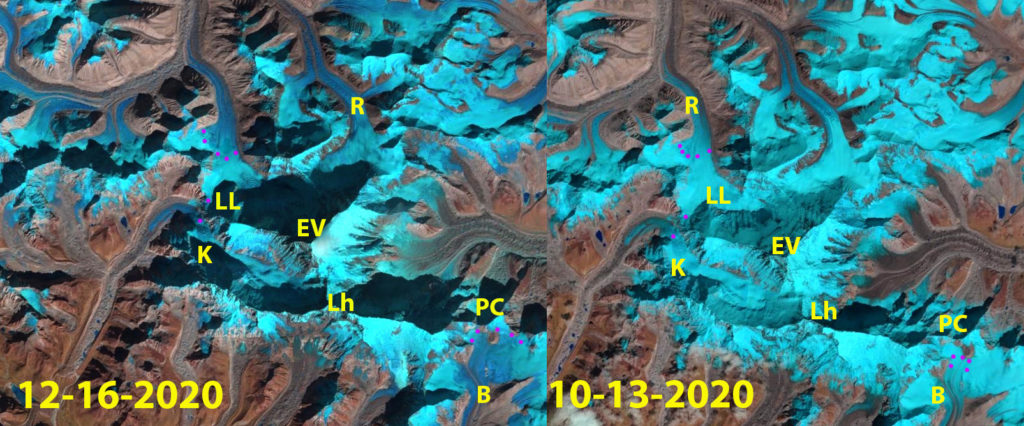

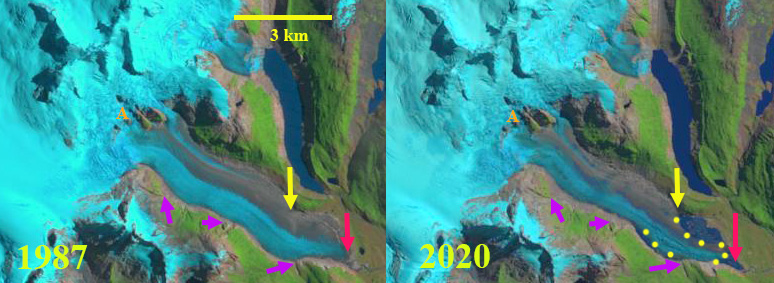

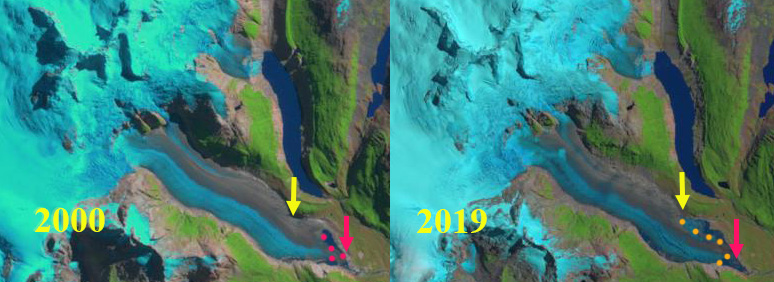

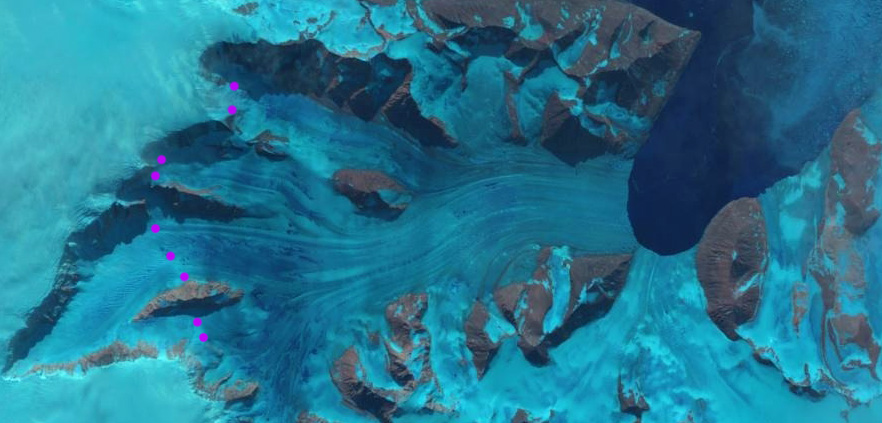

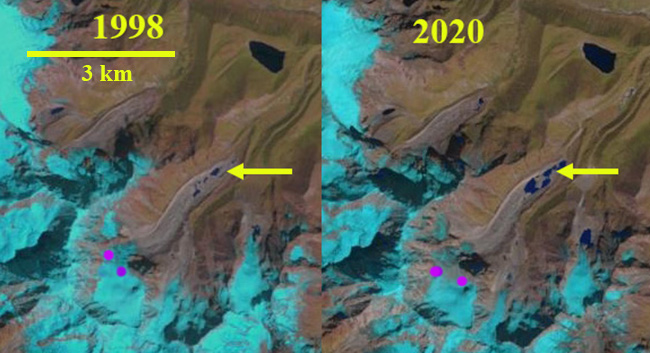

On October 13, 2020 the snowline is at 5700 m on the Gyarbarg Glacier and Bhote Khosi Glacier that flow north and south from Nangpa La respectively. At Nup La the snowline is at 5750 m short of the pass on the Rongbuk Glacier and Ngozumpa Glacier that flow north and south from the divide respectively. At Lho La the snowline is at 5700 m on Rongbuk Glacier and 5500 m on Khumbu Glacier that flow north and south from the divide respectively. At Pethangtse Col the snowline is at ~6000 m on Barun Glacier that flows south from the col. Two months later on Dec. 16 the snowline has risen above Nangpa La, allowing for a snow free crossing, and is at ~5800 m. There is also a snow free crossing at Nup La, with the snowline above the pass at 5850 m. At Lho La the snowline is below the pass on Rongbuk Glacier at 5800 m and at ~5600 m on Khumbu Glacier. At Pethangtse Col the snowline reaches the crest at the top of Barun Glacier at over ~6100 m. Nup La and Nangpa La remain snowfree through January 1, 2021, see below. The rise of ~100 m at each site since October 13 indicates significant ablation during the period, indicative of greater mass losses lower on these glaciers. Bocchiola et al (2020) report that on West Kangri Nup Glacier, tributary to Khumbu Glacier, in the 5400-5500 m range significant accumulation is no longer being retained through the summer monsoon. This is indicative of the ~100 m rise in summer freezing level since 1980 reported by Baker Perry et al (2020).

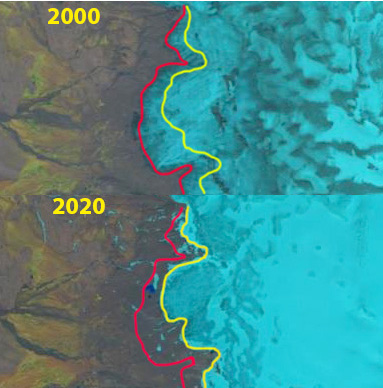

In 2015, 2016, 2018 and again in 2019 high winter snowlines indicated the same process in the Mount Everest region (Pelto, 2019). On December 11. 2019 the snowline in the Everest Region was notably high, averaging 5800 m, but high passes such as Nup La and Nangpa La still had snowcover (Pelto, 2019). There had been no significant snowfall from the end of the summer monsoon in 2019 through Dec. 11, a snow storm occurred from Dec. 12-14 (Baker Perry et al 2020). The result is an expanded ablation season that extends beyond October into December or later in the winter. The melt rates due to the limited solar radiation or sublimation are small, but are significant on many glaciers (Wagnon et al 2013). This has occurred due to increasing air temperatures since the 1980’s, with mean annual air temperatures increasing 0.62 °C per decade over the last 49 years; the greatest warming trend is observed in winter, the smallest in summer (Yang et al., 2011).In recent years a white early winter can only be found high on the glaciers of the Khumbu Region.

The Lho La (LL) and Pethangtse Col (PC) region in Landsat images from 10-13-2020 and 12-16-2020, Lh=Lhotse Peak, EV=Everest, R=Ronguk Glacier, K=Khumbu Glacier, B=Barun Glacier and purple dots indicate the snowline.

Here we continue to document the extension of mass balance losses through the post monsoon and into the winter season, which we have also reported on for the Gangotri Glacier, India and Lhonak Glacier, Sikkim. The question for Himalayan glaciers now is when does the ablation season end? The answer will depend on the specific glacier, but a combination of satellite imagery and local weather records are key to answering, such as the ongoing programs noted by Baker Perry et al (2020) and Wagnon et al (2020). The Rolex-National Geographic Perpetual Planet Expedition provides real time weather data from Everest and daily images of conditions that provide an opportunity to document the end of ablation conditions. King et al (2019) found during the 2000-2015 period mass balance losses of debris-covered and clean-ice glaciers to be substantially the same in the Mount Everest region. They observed the mass balance of 32 glaciers finding a mean mass balance of all glaciers was −0.52 m/year, increasing to -0.7 m/year for lake terminating glaciers. Dehecq et al (2018) examined velocity changes across High Mountain Asia from the 2000-2017 period identifying a widespread slow down in the region. The key take away is warming temperatures lead to mass balance losses, which leads to a velocity slow down, and both will generate ongoing retreat.

Nangpa La and Nup La in Dec. 16, 2020 (above), and January 1, 2021 (below) Landsat images indicating both are snow free, purple dots indicate snowline.

Image from Rolex-National Geographic Perpetual Planet Expedition on Dec. 16 indicating the lack of snow accumulation to date on bare rock surfaces below 5600 m in foreground including weather conditions indicating 7% humidity.

Ya

Ya