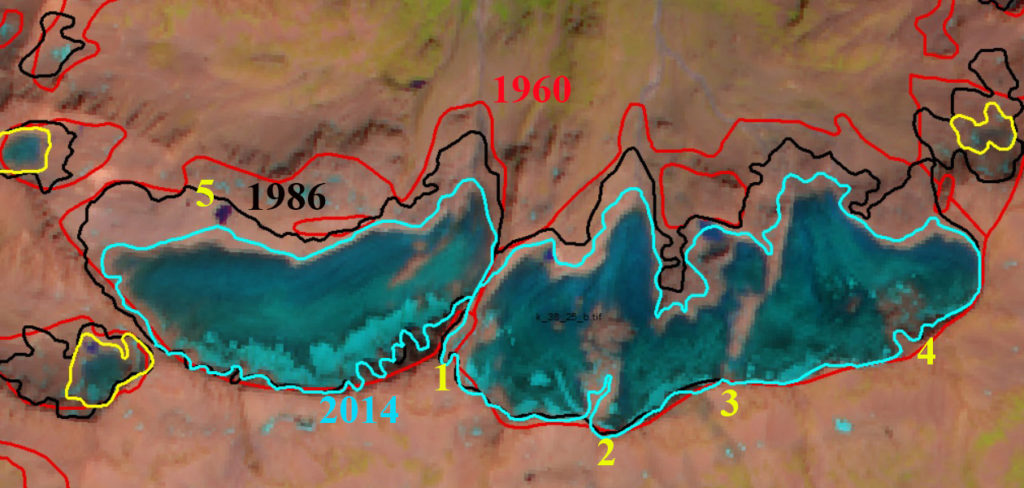

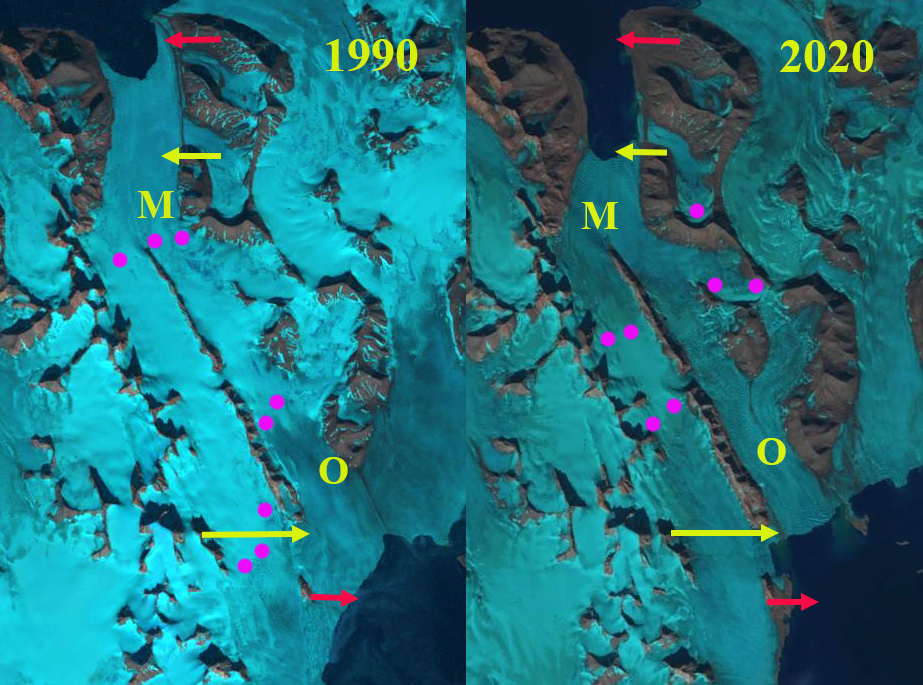

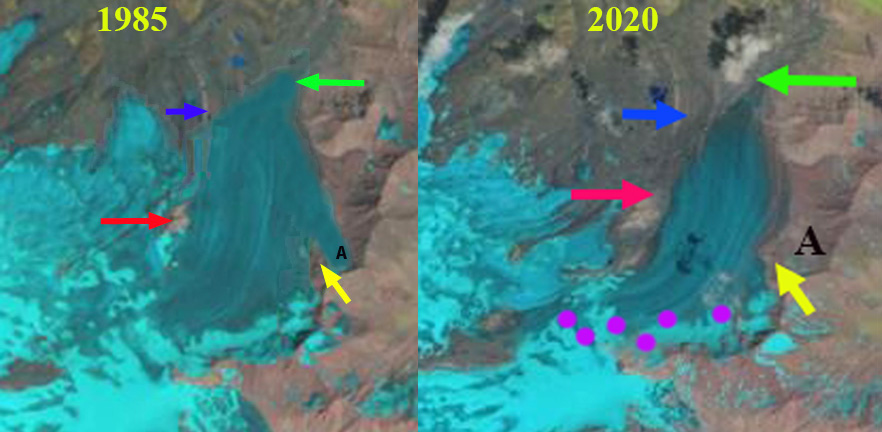

Franklin Glacier, British Columbia in 1987 and 2020 late summer Landsat images. Red arrow is the 1987 terminus, yellow arrow the 2020 terminus, and purple dots the snowline. Point 1 is the junction with Dauntless Glacier, Point 2 is the junction with an unnamed glacier, Point 3 is where Whitetip Glacier joins the glacier, and Point 4 is where Jubilee Glacier previously joined.

Franklin Glacier is one of the largest glaciers in the British Columbia Coast Range extending 24 m southwest from the summit region of Mount Waddington. VanLooy and Forster (2008) observed that of the outlet glaciers from the five large icefields in this region Franklin Glacier had the greatest retreat from 1927-1974 of 4100 m. Mood and Smith (2015) note this glacier has had many Holocene advances with the mid-19th to early 20th century advance reaching its maximum Holocene extent. Here we examine late summer Landsat images from 1987-2020 to identify the ongoing response of this glacier to climate change.

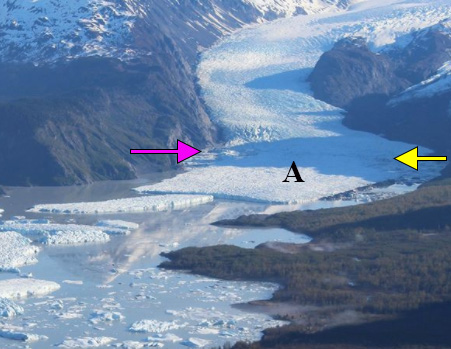

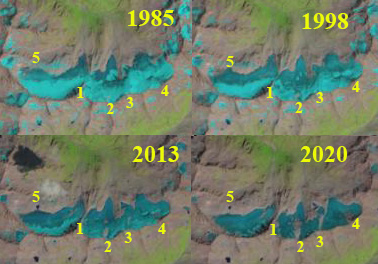

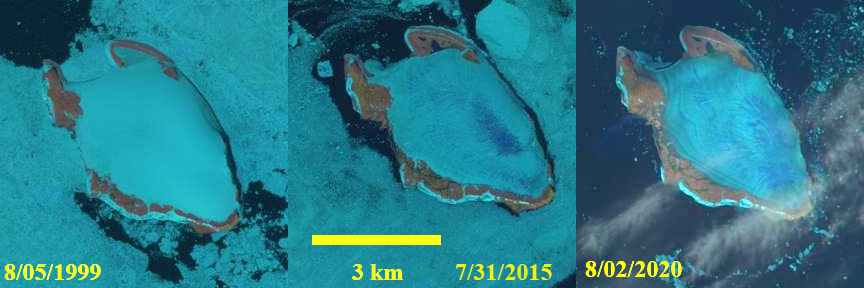

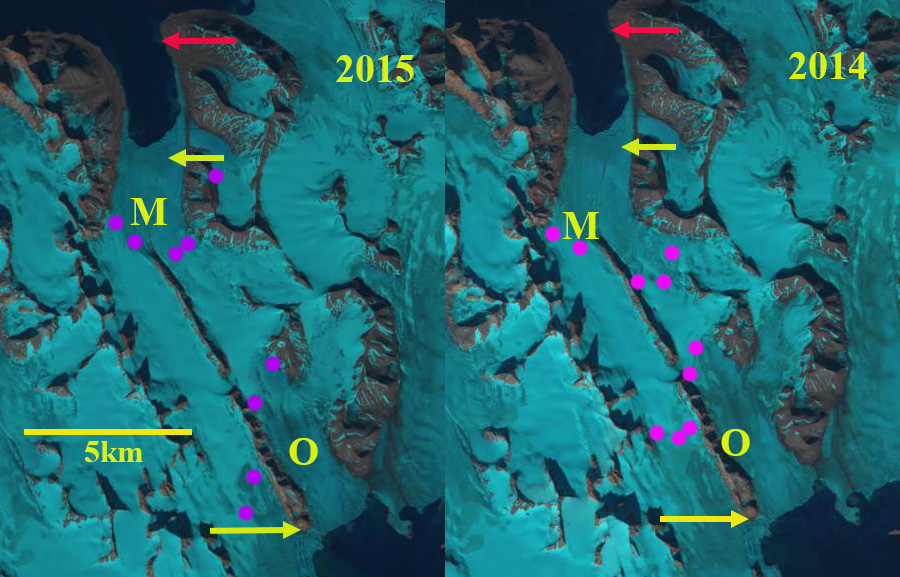

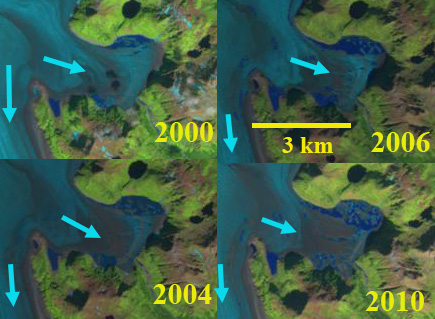

In 1987 the Dauntless Glacier (Point 1) is a tributary joining the glacier at 1300 m. The Whitetip Glacier joins the main glacier adjacent to (Point 3) averages 1900 m. The glacier separates into two main tributaries at 1800 m, with the snowline in 1987 being at m. In 1995 the glacier retreat from the 1987 position, red arrow is evident, the snowline is at 1950 m. By 2000 the glacier has retreated ~900 m in the previous 13 years, the snowline is at 1900 m. In 2014 Dauntless Glacier (Point 1) has separated from Franklin Glacier. The snowline in 2014 is at 2050 m. In 2017 the snowline is at 2100 m. The trimline on the north side of the main trunk of the glacier between Point 3 and Point 4 that illustrates thinning is quite apparent and illustrates reduced thinning with distance upglacier. There is a low surface slope of the glacier upglacier of Point 4 to Point 1 which hints at the potential of a basin where a proglacial lake could form. In 2019 the snowline is at 2100 m. By 2020 the glacier has retreated 2700 m from the 1987 position, the rate of ~120 m/year is an increase from the 20th century rate after 1927. The unnamed tributary at Point 2 is detached from the main glacier. The snowline is at 2050 m in early September, 2020 dropping to 1700 m at the end of September. The high persistent snowlines averaging ~2100 m since 2014 indicate continued mass loss and increased retreat, this is also higher than the 1900 m ELA reported by VanLooy and Forster (2008).

Menounos et al (2018) identified a mass loss for glaciers in this region of ~0.5 m year from 2000-2018 which is driving retreat. The retreat rate during this period is slightly less than the 130 m/year at Bridge Glacier,or Klinaklini Glacier, and slightly more than at Bishop Glacier and Klippi Glacier. The retreat has been more consistent, likely due to the fact there has been no proglacial lake at the terminus during this period. Franklin Glacier begins at an elevation of 3300 m, this results in the glacier continuing to have a significant accumulation zone in todays climate.

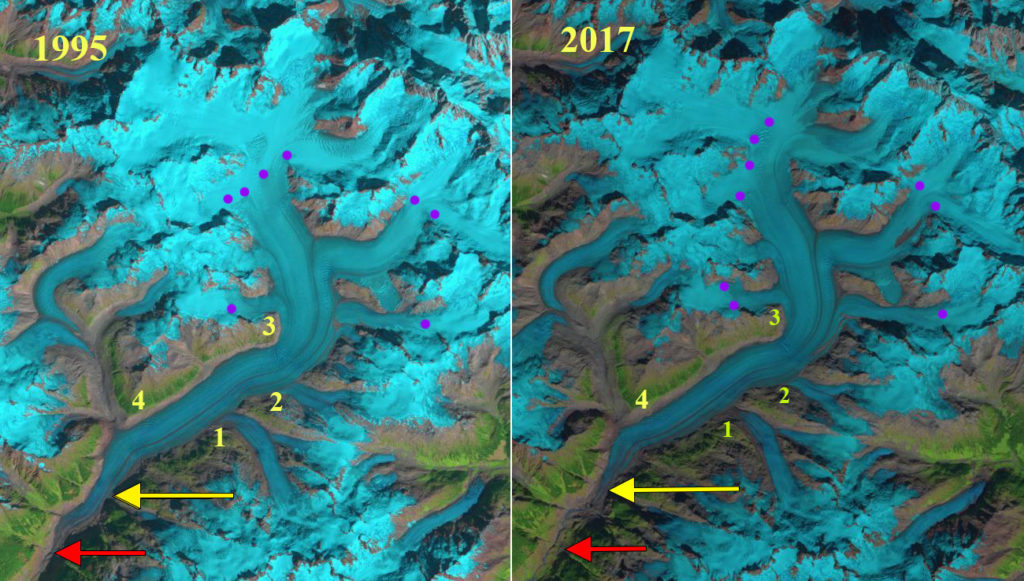

Franklin Glacier, British Columbia in 1995 and 2017 late summer Landsat images. Red arrow is the 1987 terminus, yellow arrow the 2020 terminus, and purple dots the snowline. Point 1 is the junction with Dauntless Glacier, Point 2 is the junction with an unnamed glacier, Point 3 is where Whitetip Glacier joins the glacier, and Point 4 is where Jubilee Glacier previously joined.

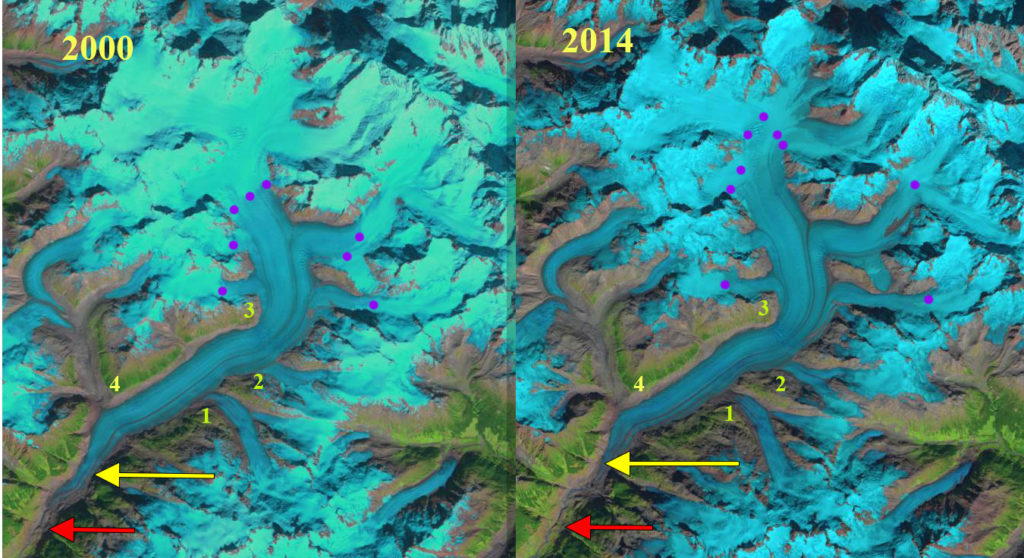

Franklin Glacier, British Columbia in 2000 and 2014 late summer Landsat images. Red arrow is the 1987 terminus, yellow arrow the 2020 terminus, and purple dots the snowline. Point 1 is the junction with Dauntless Glacier, Point 2 is the junction with an unnamed glacier, Point 3 is where Whitetip Glacier joins the glacier, and Point 4 is where Jubilee Glacier previously joined.