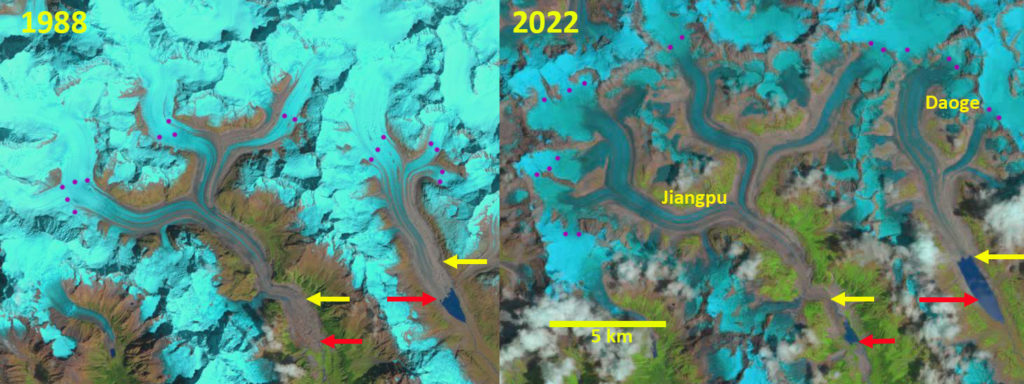

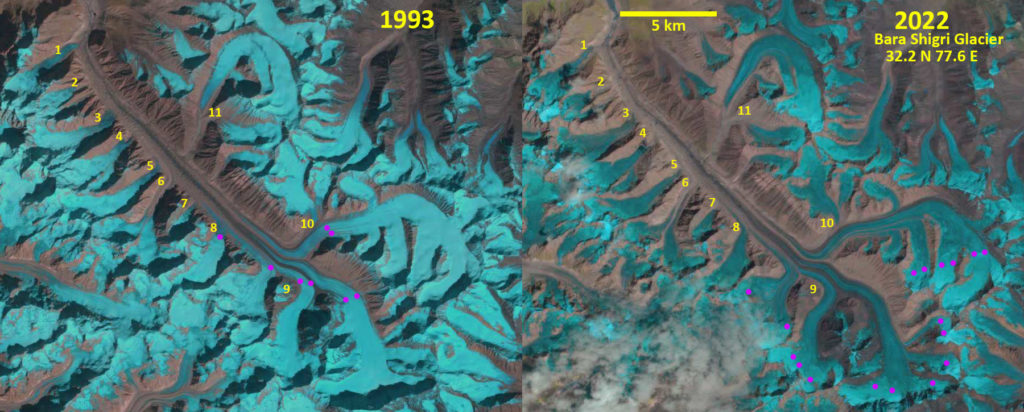

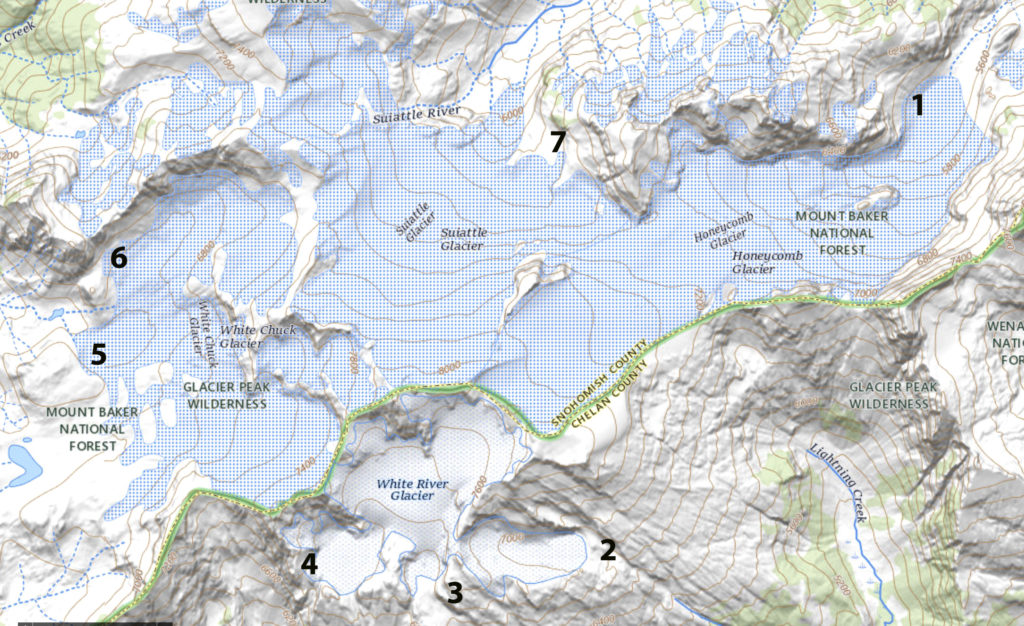

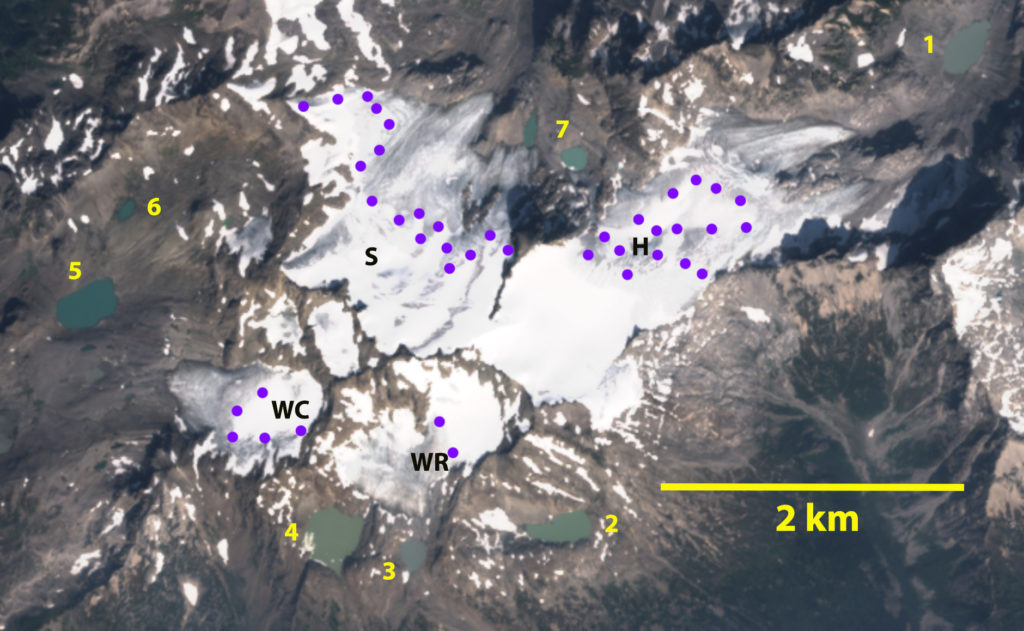

Himan Glacier in 1958 USGS map and in 2022 Sentinel 2 False Color image. The three ice masses with an area greater than 0.01 km² are indicated.

Hinman Glacier had descended the northwest flank of Mount Hinman in the North Cascades, Washington and based on 1958 aerial photographs, Hinman Glacier the USGS had listed this as the largest glacier in the North Cascades south of Glacier Peak with an area of 1.3 km² (Post el al 1971). In 2022 the glacier is gone with the largest relict fragment of ice at 0.04 km². This is the story of this glaciers demise that as documented by the North Cascade Glacier Climate Project, that for 40 years has observed in the field the response of glaciers to climate change.

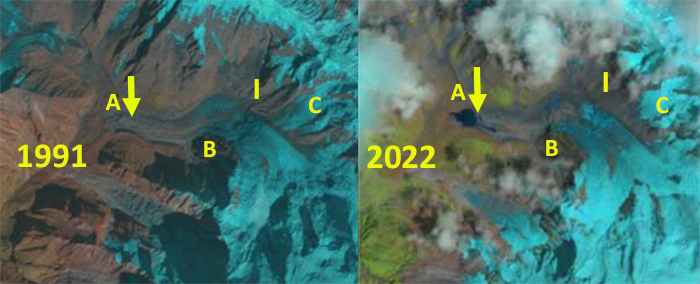

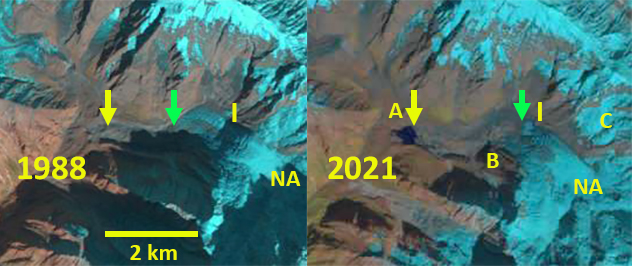

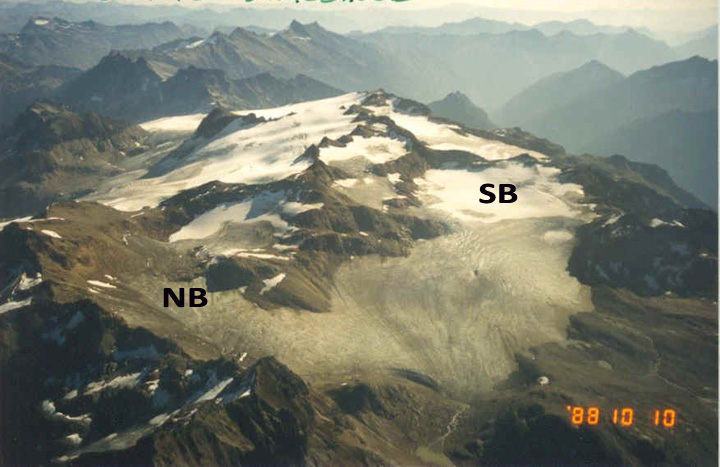

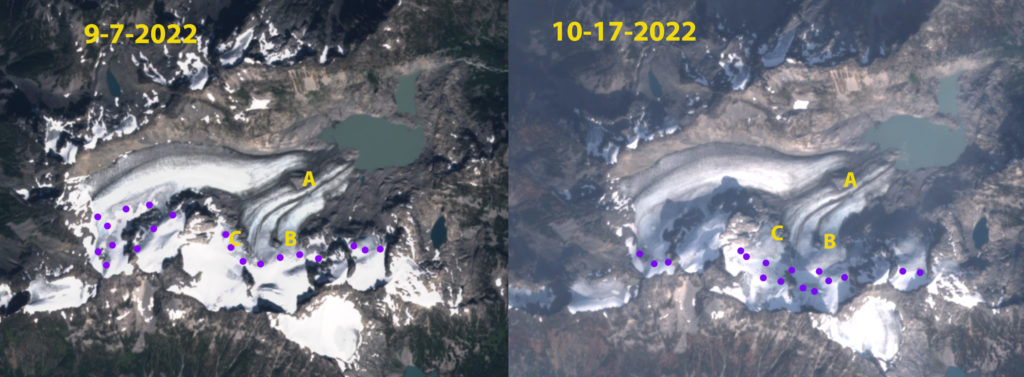

Hinman Glacier in 1988 with 4 distinct ice masses.

In the 1960’s the glacier extended from the ridge top of Mount Hinman at 2250 m to the bottom of the valley at 1675 m. In 1988, Hinman Glacier from the west was a group of four separated ice masses that we surveyed. The amount of blue exposed that year indicates the glacier lacked a consistent accumumulation zone. This is indicative of a glacier that cannot survive (Pelto, 2010). In 1992 we mapped the largest of these remaining ice masses at 0.12 km², this was another year with only pockets of blue ice left. In 1998 the glacier has a few areas of blue ice are seen, the glacier was 20% of its mapped size 0.25 km².

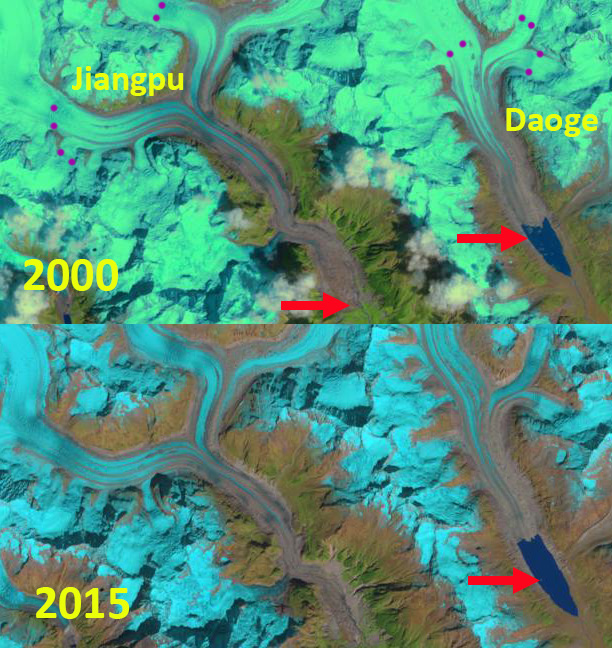

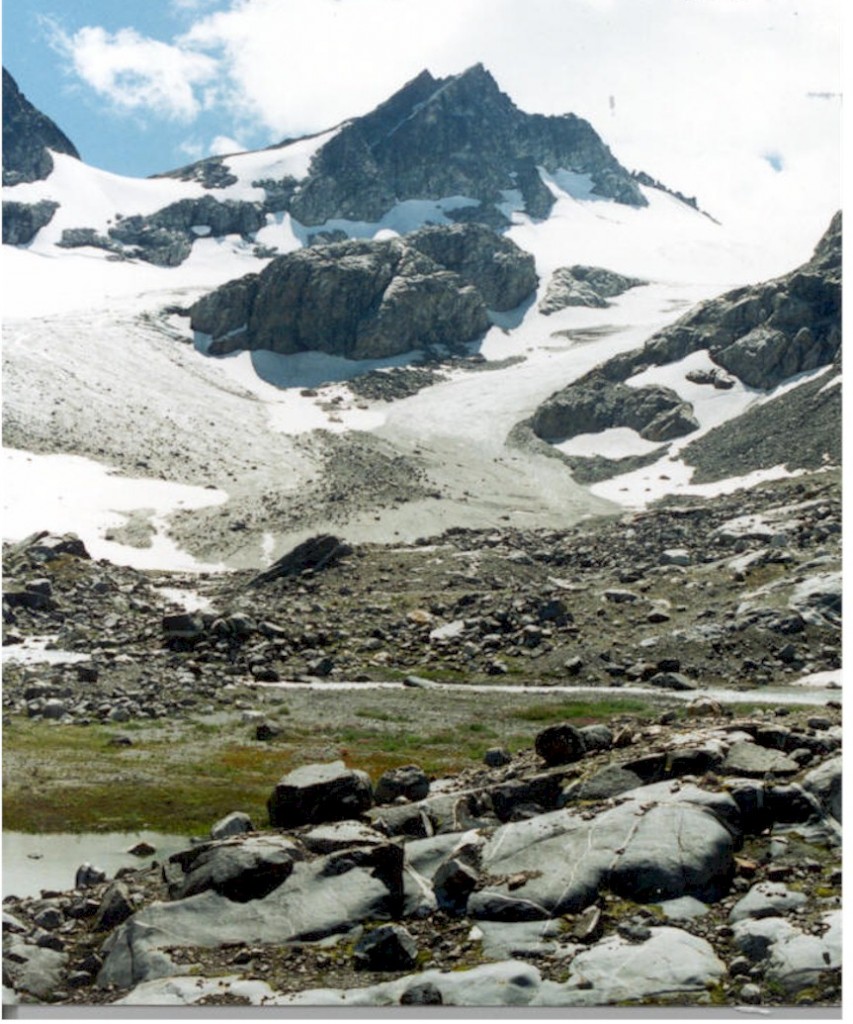

In 2005 we observed how thin the ice was including being able to see rock at the bottom of several crevasses (see below). In 2006, from a Google Earth image,at this point the glacier is no longer detectable under the snowcover that persisted that summer, note the map outline and the gorgeous new “Hinman” Lake The new lake is 1 km long. A 2009 view from the far end, north end of Lake Hinman up the valley and mountain side that was covered by the Hinman Glacier, now 90% gone. Each of the two larger ice masses from 1998 is now divided into at least two smaller portions. By 2022 the ice fragments have further diminished with the largest just 0.04 km2, less than 4% of its 1958 size. The tendency of this former glacier to be bare of snowcover by late August in many years, is what led to the rapid loss. This same story is playing out on Foss Glacier on the other side of the ridge, though not as quickly.

Hinman Glacier thin sections of ice fragmenting in 2005.

The loss of glacier area of this glacier and in the Skykomish River Basin has impacted summer runoff in the Skykomish River watershed. From 1958-2009 glacier area declined from 3.8 km² to 2.1 km², (Pelto, 2011), and in 2022 has further diminished to 1.7 km², a 55% reduction. We have monitored all four major glaciers in the basin Columbia, Foss, Hinman and Lynch Glacier, the primary glaciers in the basin, declined in area by 25%, 70%, 95% and 40% respectively since 1958. Despite 15% higher ablation rates during the 1985-2022 period, the 55% reduction in glacier area led to a 40-50% reduction in glacier runoff between 1958 and 2022. The impact on the Skykomish River is evident.

Glacier runoff on Hinman Glacier heading the Skykomish River. Streams like this used to drain across the glacier all summer long. Now they no longer exist to feed the Skykomish in late summer.

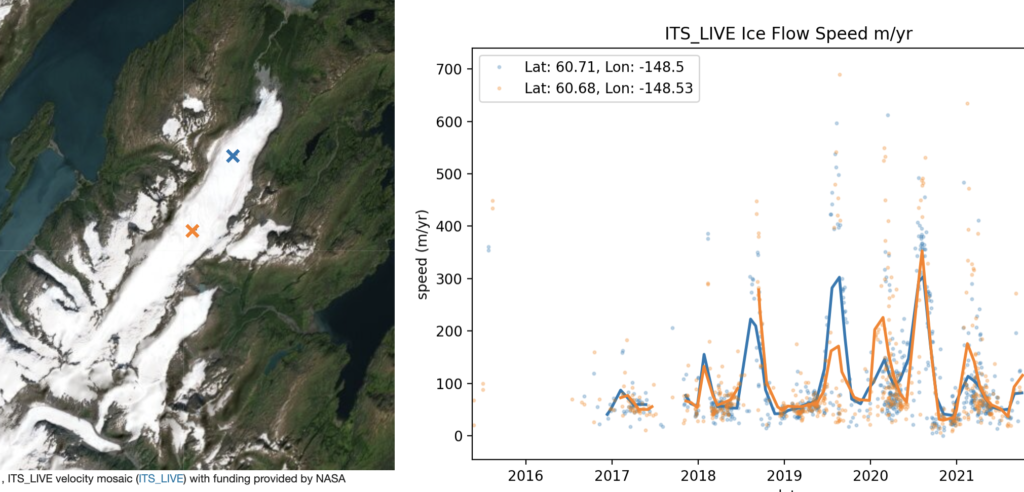

A key threshold of in-stream flow levels considered insufficient to maintain short term survival of fish stocks is below 10% of the mean annual flow (Tennant, 1976). For the Skykomish River 10% of mean annual flow is 14 m3s-1. In the Skykomish River from 1958-2021 there have been 363 melt season days with discharge below 14 m3s-1. Of these only three occurred before 1985, and 67% have occurred since 2003. The loss of 55% of the glacier runoff is a key reason for the onset of critical low flow days. Of more concern for aquatic life is the occurrence of extended periods of low flow (Tennant, 1976). From 1929-2021 in the Skykomish River basin there have been 12 years where streamflow dropped below 14 m3s-1 for 10 consecutive days during the melt season, 1986, 1987, 1992, 1998, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2021 and 2022. Precipitation has not declined during this interval, hence earlier snowmelt, reduced glacier runoff and greater evapotranspiration must be causing the increase in late summer low flow periods.

In 2022 a cool start to summer allowed snowpack to persist in the basin into August. Runoff was strong from Columbia Glacier on Aug.1 as we forded the outlet stream, see below. By September glaciers represented the main area of melt. An extended warm period extending into October led to persistent low flow conditions, below 495 cfs (14 m³/sec), from Sept 9.-Oct. 20.

The former Himan Glacier from the new”Hinman” Lake that has formed since 1958 with glacier retreat, 3 small ice patches remain in this 2009 view.

Hinman Glacier basin in 2006 Google Earth view, with “Hinman Lake”.

Himan Basin in Open Elevation map and in 2022 Sentinel 2 False Color image.

Streamflow and temperature in the Skykomish River at the USGS site at Gold Bar. Period of low flow begins after flow drops below ~500 CFS.

(https://waterdata.usgs.gov/monitoring-location/12134500/)

Fording headwaters of North Fork Skykomish, which is the runoff from Columbia Glacier, on 8-1-2022.