Videla Glacier is a land terminating glacier in the northwest portion of the Cordillera Darwin Icefield (CDI) in Tierra del Fuego, Chile. The glacier has terminates in several expanding proglacial lakes each in front of a different tongue of the glacier. The glacier flows northwest from Cerro Ambience towards Fiordo Profundo. Meier et al (2018) identified area change of Patagonia glaciers from 1870-2016 with a ~16% area loss of CDI, with more than half of the loss occurring since 1985. They also noted that CDI glaciers were retreating fastest between 1986 and 2005. Izagirre et al (2025) identified a 124% increase in glacier lake area from retreat between 1945 and 2024. The retreat has been largest on tidewater glaciers such as Marinelli Glacier and Ventisquero Grande Glacier.

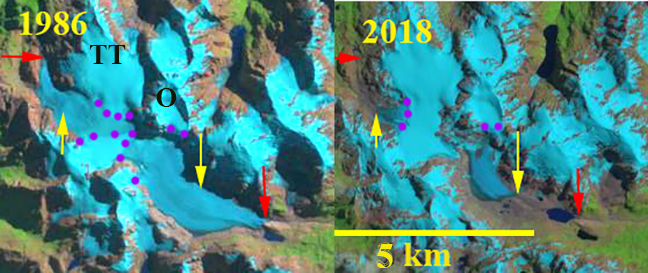

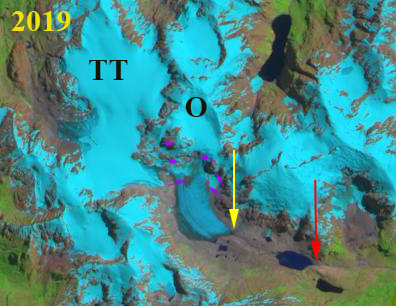

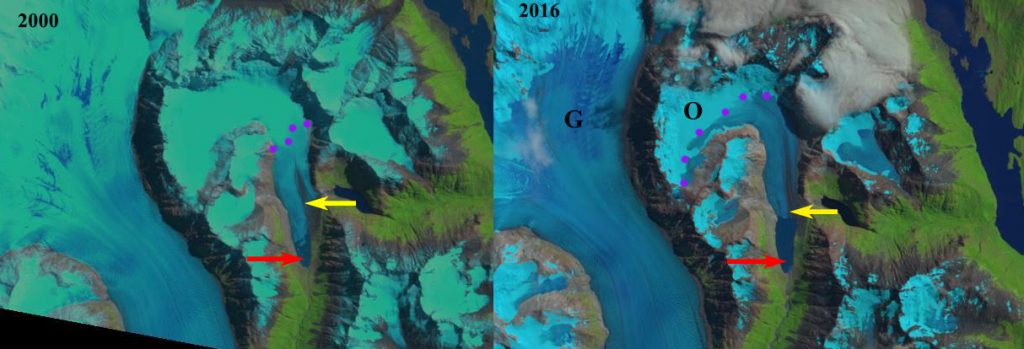

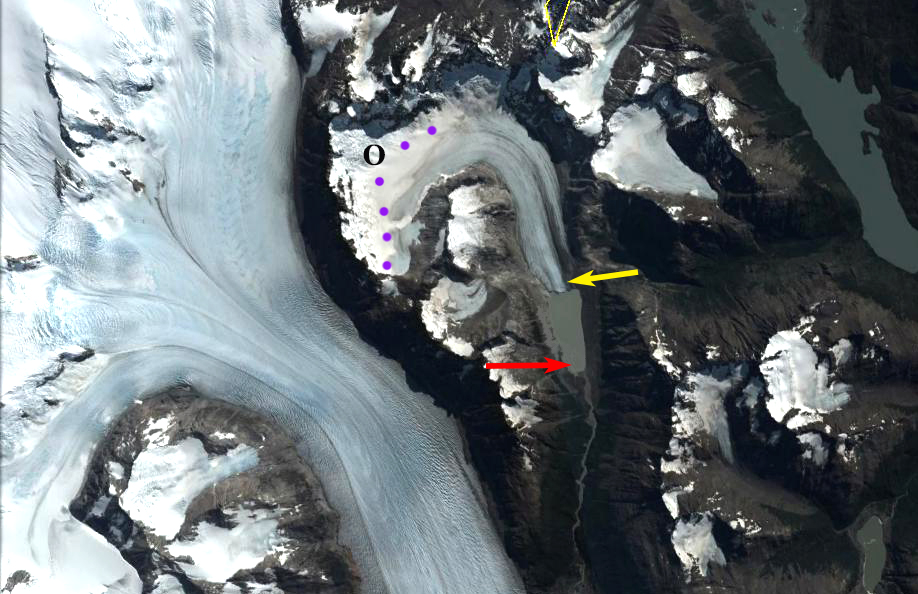

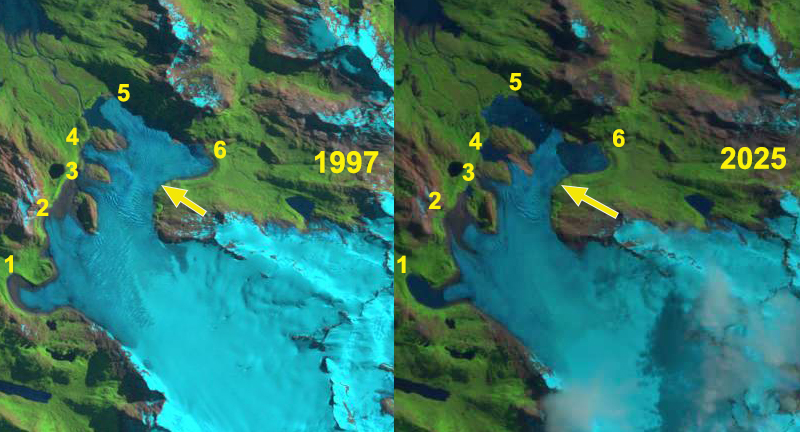

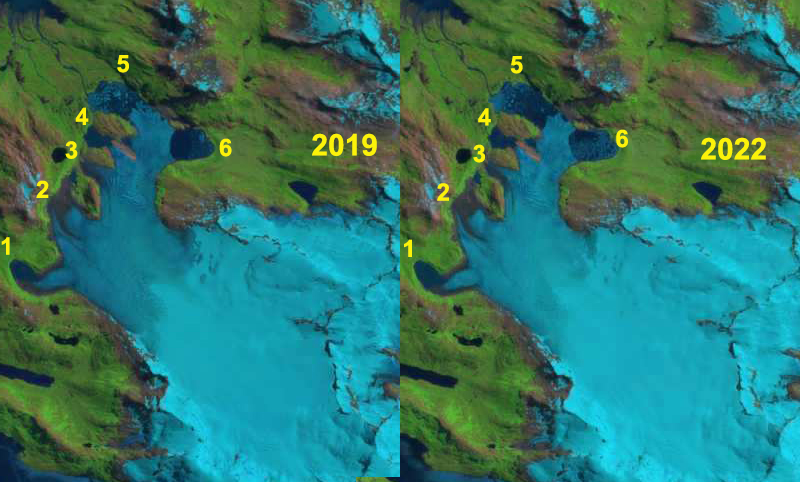

In 1997 of Videla Glacier’s six main terminus lobes, five did not exhibit a proglacial lake, only the two northern most lobes (Point 4, 5, and 6) ending in a fringing yet to develop proglacial lake. The terminus lobes at Point 2 and 3 were joined. By 2019 lobes 1 and 4 had developed significant proglacial lakes, while the main terminus at Point 5 and 6 had opened up two halves of the same proglacial lake. The terminus lobes at Point 2 and 3 had separated. A rib (yellow arrow) was developing upglacier of the main terminus indicating thinning and reduced flow. A new lake had developed just downstream of this rib.

In 2025 the terminus at Point 1 had receded 950 m creating a 0.75 km2 proglacial lake. Terminus Lobe 2 and 3 had separated by 400 m. At Point 4 a 0.5 km2 proglacial lake had formed with the 1050 m retreat. The main terminus at Point 5 and 6 extends across the lake basin in a narrow 350 m wide tongue. The lake has grown to 3 km2, with 1.5 km of recession from Point 6 and 1.8 km from Point 5. This narrow tongue may well break off this coming summer.

Videla Glacier, Chile ongoing retreat and proglacial lake growth at terminus lobes (1-6) illustrated by Landsat images from 2019 and 2022.