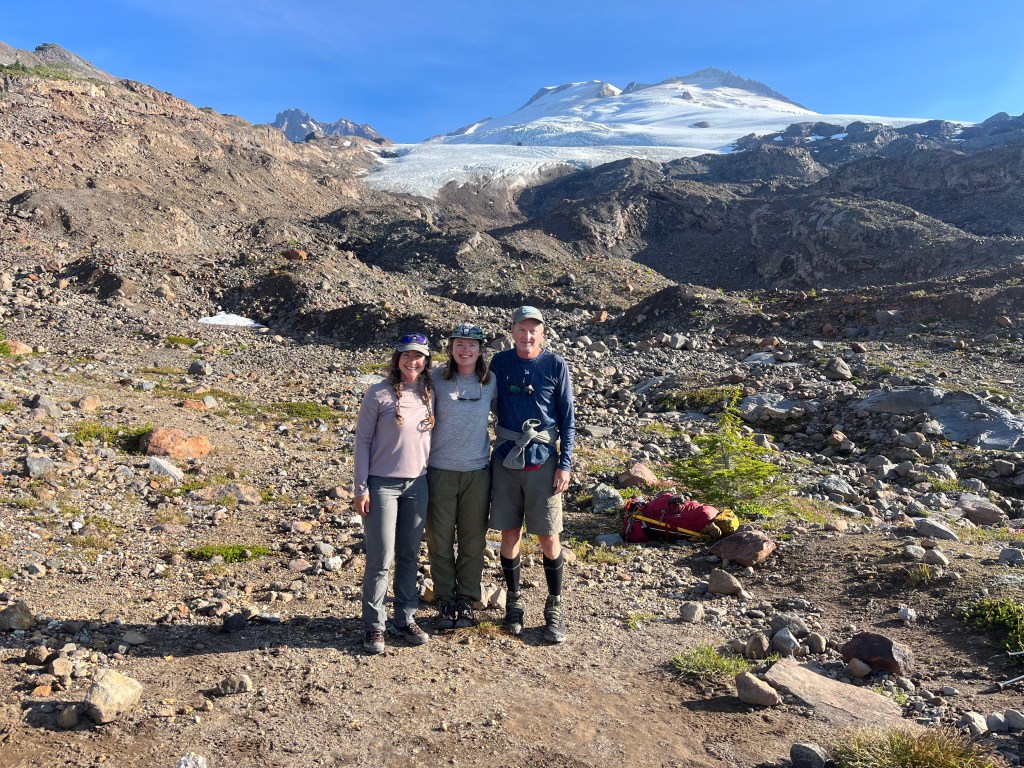

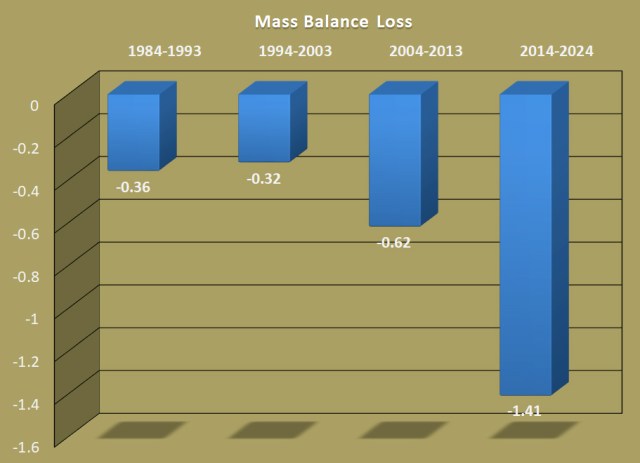

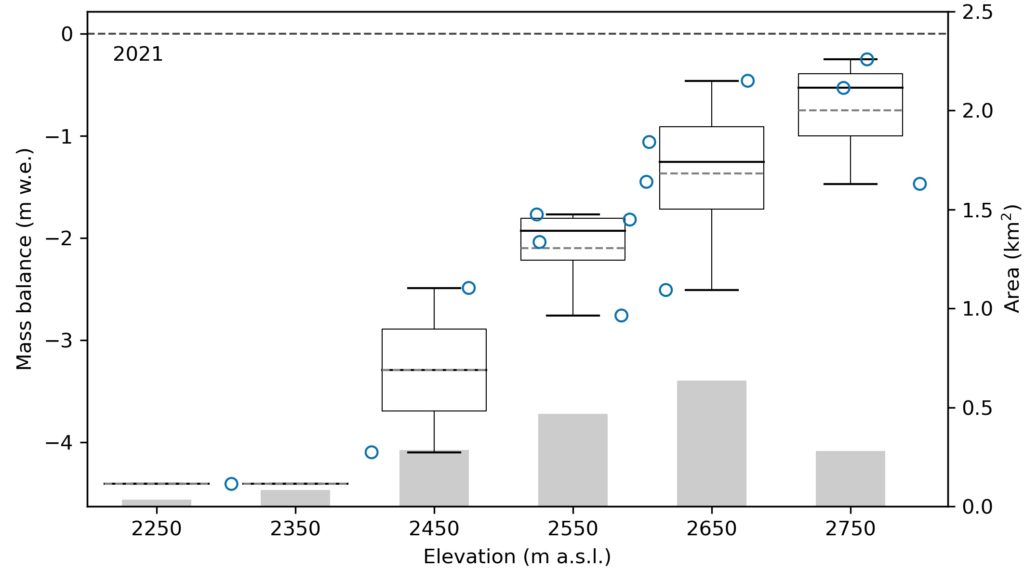

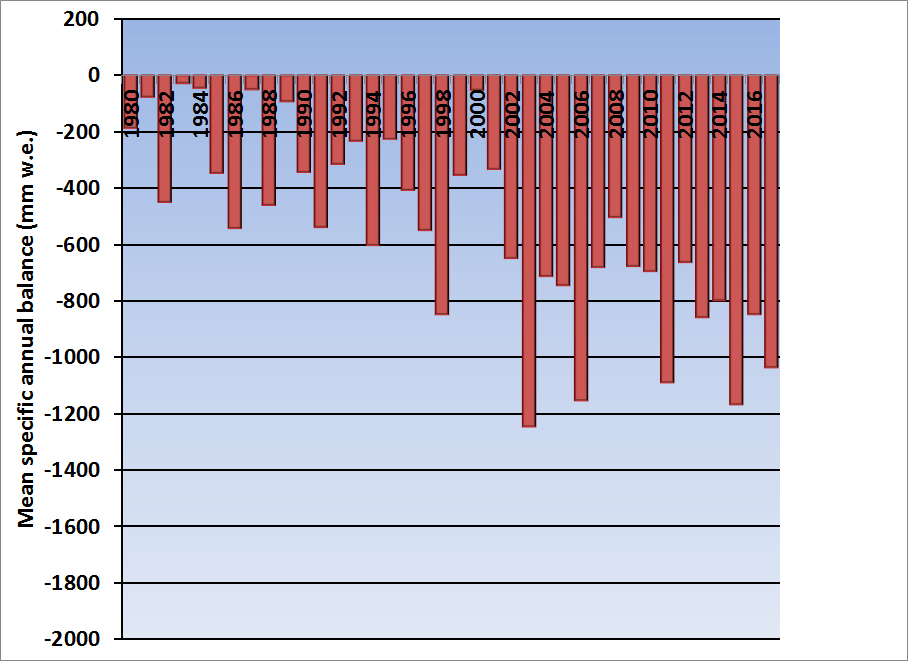

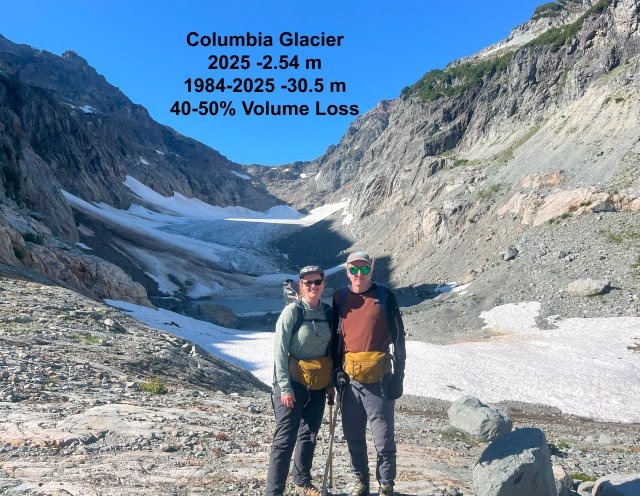

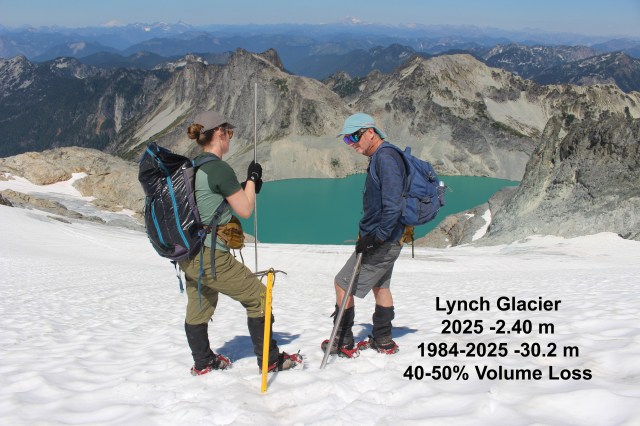

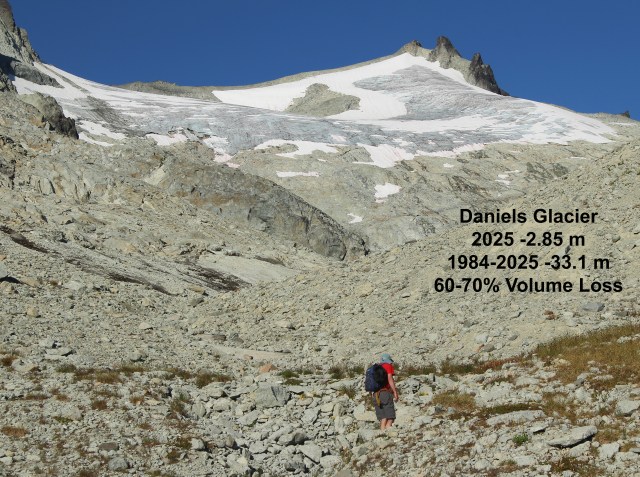

We hiked into North Cascade glacier to complete detailed observations for our 42nd consecutive year. These annual observations provide a detailed assessment of their response to climate change. For the third consecutive year North Cascade glacier on on average lost more than 2 m of glacier thickness. This cumulative loss of 7-8 m on most of the ranges glaciers that average 25-40 m in thickness represents 20% of their volume lost in just three years. On a few of the largest glaciers, such as those on Mount Baker that average 40-60 m in thickness the loss represents 12% of their volume lost.

The consequence is an acceleration of the collapse of the North Cascade glacier system. This landscape that has for long been shaped by ice is rapidly losing that glacier element. The rate of retreat for the glaciers we work on has accelerated so quickly that we are faced each year with changing terrain and new challenges. Beyond that, we are starting to really see the effect this retreat and the decrease in water has on the ecosystems both near the glaciers and further downstream. During the field season we love seeing the wildflowers, eating blueberries, and counting mountain goats. These are all parts of a habitat that is built around glaciers and snowpack. Seeing these shifts has been really difficult, but it helps to still return to these landscapes and continue to tell their stories through science and art. Below the story is told in images with captions by each of us who participated.

Two things that stood out during the 2025 field season were the strength of our collaborations, and the changing resources the glaciers are able to provide to the surrounding ecosystem. This visible change attracted the attention of KING5-Seattle NBC affiliate and CBS Morning News. At the bottom of this post the resulting footage is embedded. The film “Shaped By Ice” Jill and I worked on with Dan McComb has been a finalist in two recent film festivals, this footage also at bottom of this long read post.

We worked with two oil painters, one watercolor painter, one printmaker, two news film crews, a team of botanists, and more. The result of all these collaborations has led to so many great stories being created and shared about our collective work. It also meant our core group of field assistants had to be flexible to a changing group and the sometimes difficult and imperfect logistics that accompany that. -Jill Pelto

This photograph of an icefall at 2000 m (6700 ft) on the Easton glacier encompasses the wide range of emotions that I felt working on these glaciers this summer. The focal point of the picture is the wound inflicted upon the glacier by our changing climate. Bedrock and sediment creep through the gaping wound in the lowest icefall of the Easton, the opening visible for the first time in the project’s 42-year history. The place also holds a beauty, a sense of majesty that cannot be diminished by the tragic context of our work. The seracs at the top of the scene lean at impossible angles, destined to crash down onto the slope below, piercing the quiet of the snowy expanse in dramatic fashion. The dark annual layers in the glacier speak to the age of the ice, flowing down the flank of Mt. Baker over decades. The landscape has been a facet of my life for the past few years, as it falls upon the Easton Glacier route to the mountain’s summit. The icefall has always drawn me in as I pass, sparking a profound sense of wonder. It makes me deeply sad to see the beauty of such special places diminished, sad in a way that little else does. Over the past few years, I’ve come to like visiting these places to visiting an elderly loved one. While time may change them and even take them away from us, their beauty and meaning to me will hold true.-Emmett Elsom

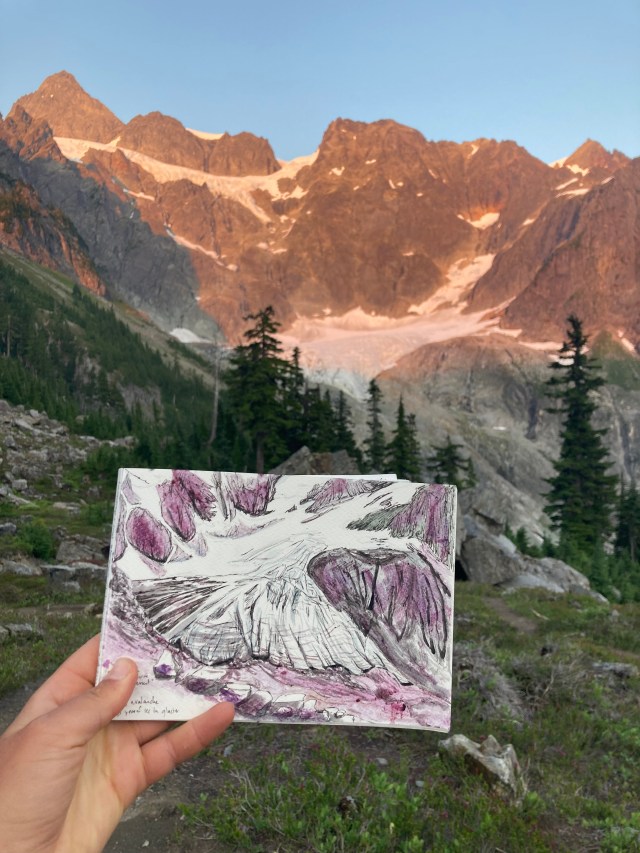

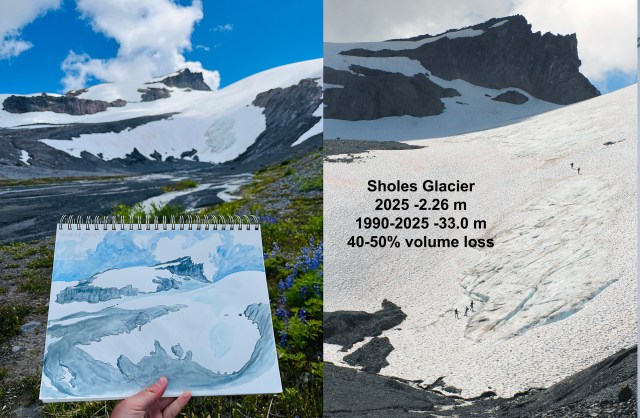

How does being present in a place shape our understanding? To the left is a view of Sholes Glacier, complete with my on-site rendition. I can’t express how lucky I feel to have had the chance to experience these places first hand. To interact with a place by attempting to capture its likeness — paying attention to the negative space not only between the white snowpack and black exposed rock, but in the empty, carved-out area that used to be filled with ice. Experiencing the texture of the glacier under your feet, the cool air drifting off the snow, the good tired feeling of your body after physically traversing top to bottom. This is what you don’t get from a photo. To know places such as these is to love them and see their role in the world, and want to protect them. But so many never get the chance to understand them this way.-Claire Seaman

This field season I focused on exploring the once-barren foreland a glacier leaves behind. Studying the plants growing in the wake of the Easton Glacier made me reflect on the way life responds to these major changes. This photo of a bright monkeyflower cluster in the streambed of the nearby Sholes Glacier exemplifies this resilience and optimism to me. The Sholes, in the background, drains a lifeblood that will feed the watershed downstream into the Nooksack, supporting people, fisheries, and a whole riparian ecosystem. The eventual loss of glacial ice feeding the river will be catastrophic, yet the scarred space left behind will blossom with vegetation. Witnessing firsthand how staggering the extent of glacial retreat is can be overwhelming, but that bright patch of flowers stands as encouragement. Alone in an altered landscape, those flowers will pave the way for more to follow. Change is nuanced, and as we watch it occur we can change, sharing stories of the beauty of this environment supported by ice, and adapting our lives and policies in a way that can be the difference which keeps glaciers flowing.-Katie Hovind

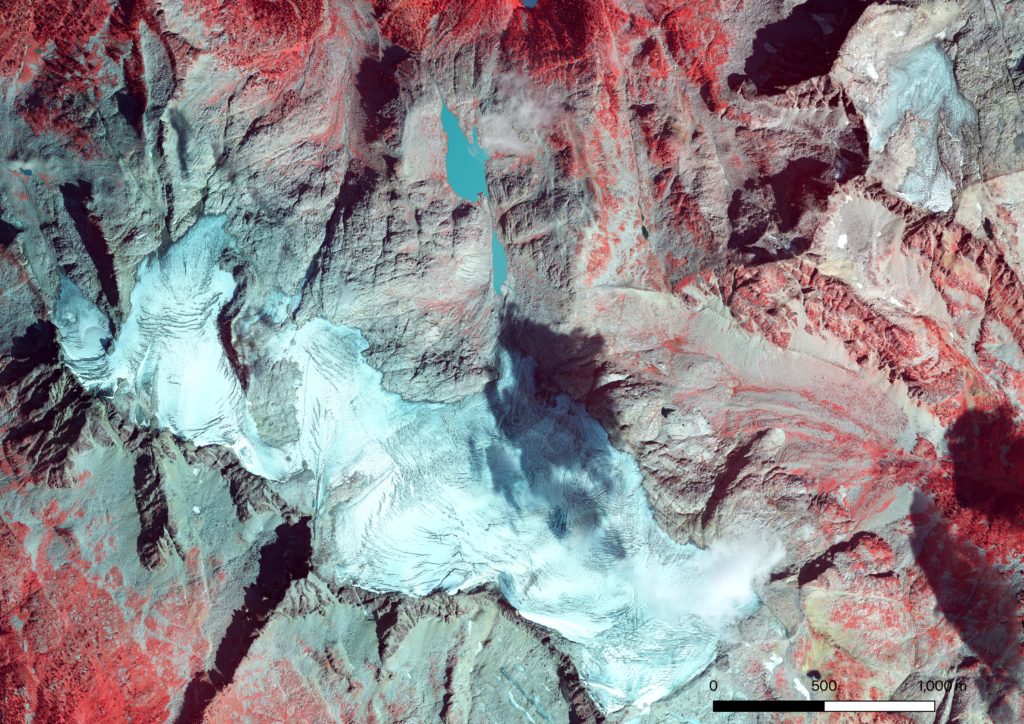

As a backcountry skier and oil painter focused on winter landscapes of the North Cascades, the idea of painting glaciers in the field was a dream come true! I knew what we would see and learn about the health of our glaciers from the scientists would be highly emotional, but the power of these environments disappearing in our lifetimes is something my words fail to communicate how devastating that feels. During the study on Rainbow glacier I caught on film the moment a serac collapsed, loudly crashing, crumbling from a newly melted out rock knob down the mountain splitting into smaller and smaller pieces. It looked sickly as it broke before our eyes. Another unique experience was going into a teal, translucent, otherworldly ice cave. I have started 2 paintings to capture this vanishing environment. My goal is to assist the project in translating the study’s findings through landscape paintings that communicate the beauty of these places with titles that call attention to the retreating glaciers in the North Cascades. We all have a responsibility as humans to make individual changes to combat climate change and vote like fresh water and air depends on it, because it does. -Margaret Kingston

I write this at the end of the 2025 hydrological year, waiting for winter snow to shelter the land I love in a cool white blanket. The devastation of the alpine glaciers has surfaced so frequently in conversation these last couple months. Those who have seen the mountains are alarmed as beds of ice they once knew to be hundreds of feet thick look shallow and frail, ice pitches that were once climbed are now grey gullies of rock, and volcanoes which have always been white are unnervingly gray and shrouded in smoke. The realities of climate change in the Northwest are clear.

It is a painful time to care about the glaciers of the Cascades. Witnessing the erosion of something so much older and bigger and impactful than myself is staggering. There is much action to be done in this new terrain but for now, I come back to this: I sit in the dying glaciers warm light as the sun rises, summon the deepest snowfall in years and tell the glacier that we care, that we were grateful for all the help watering our food and feeding our oceans and making sure our salmon had somewhere to live. We are here because of you. -Cal Waichler

The trajectory for most North Cascade glaciers is one of fragmentation. This is illustrated by Foss Glacier on the east flank of Mount Hinman, that we began observing annually in 1984 but stopped measuring as it fragmented. Foss Glacier from the top was a 1 km long and nearly 600 m wide glacier. In Sept. 2025 Cal Waichler captured view from the top with the two main fragments now less than 50 m wide and 300 m long.-Mauri Pelto

Leah Pezzetti KING5 meterologist hiked in with us to Lower Curtis Glacier.