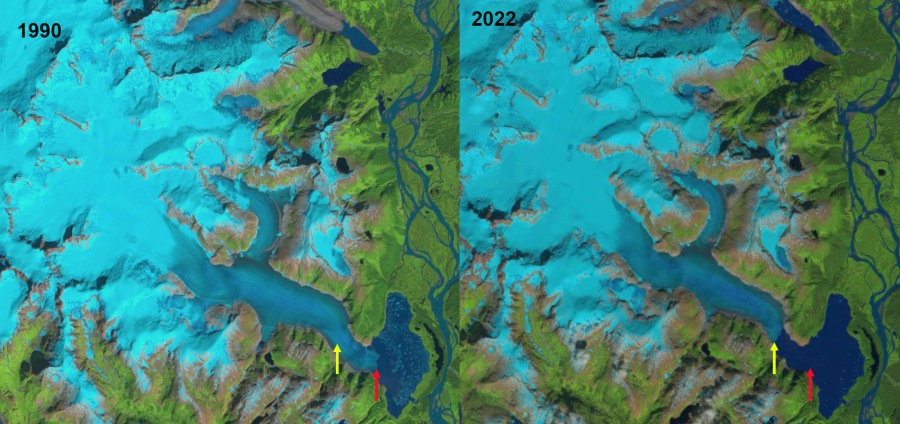

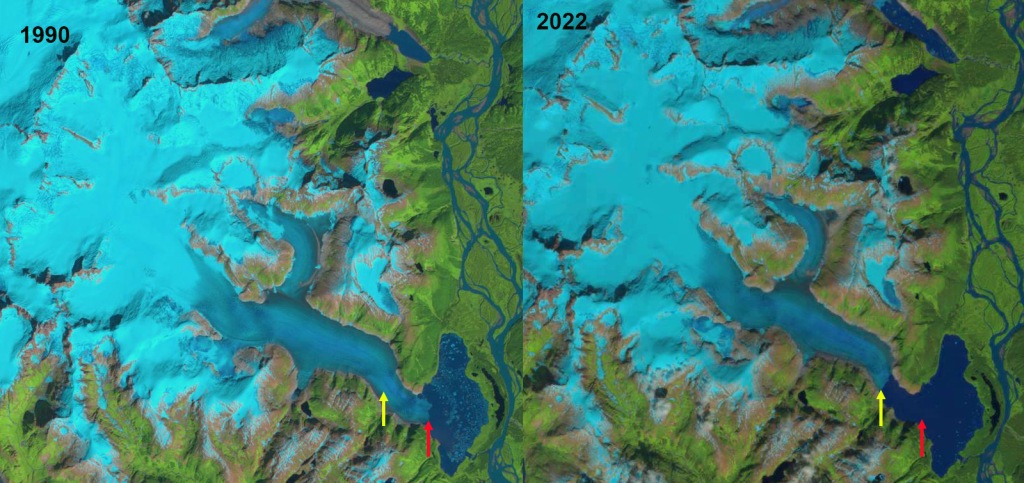

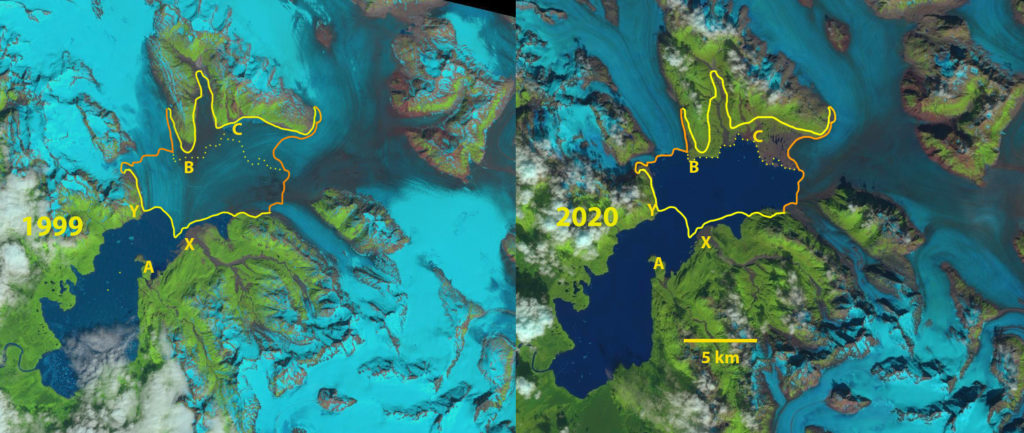

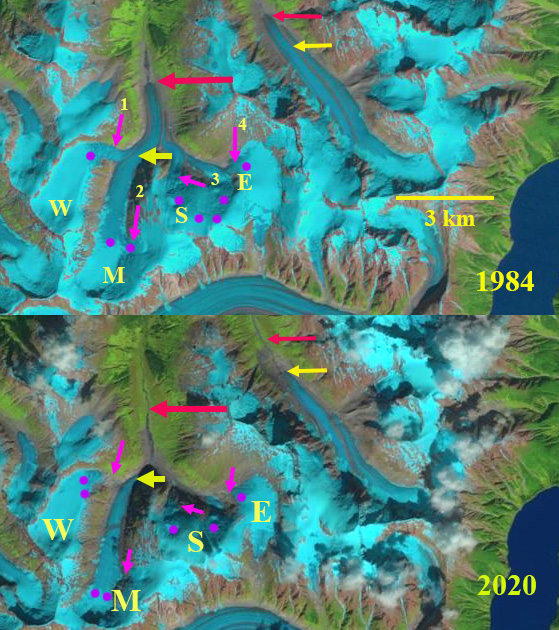

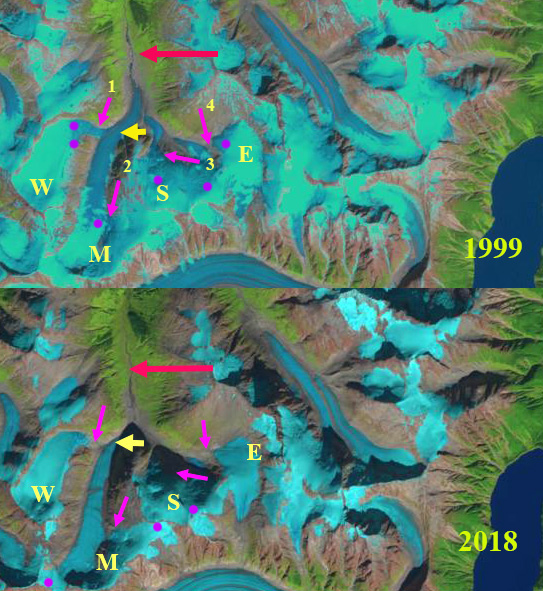

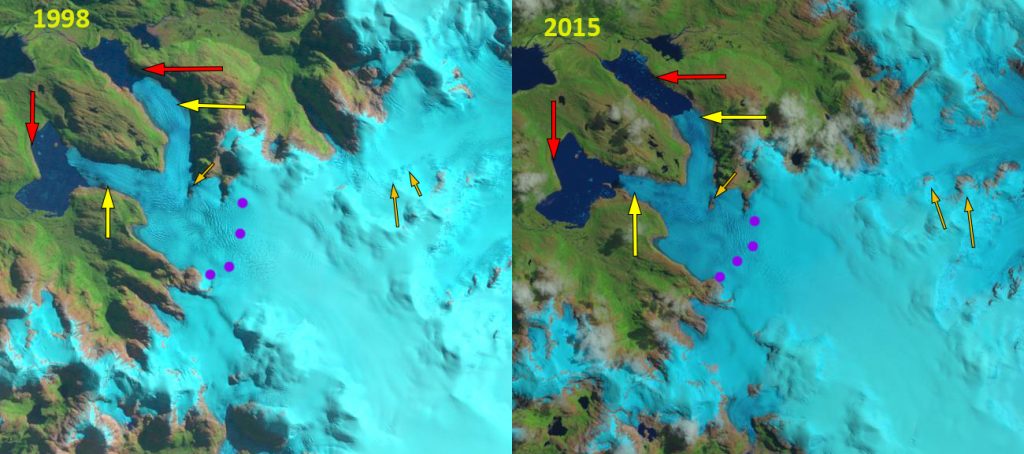

Yakutat Glacier, Alaska in 1999 and 2020 Landsat image illustrating expansion of Harlequin Lake by 40.5 km². Yellow line is the 1999 margin, orange line is the 2020 margin, and yellow dots indicate the margin of the lake shoreline. Point A indicates the 1987 terminus location, Point X and Y the 1999 terminus location. Main terminus now extends south near Point C. Northern terminus extends west from Point B.

Yakutat Glacier, Alaska has experienced a spectacular retreat in the last decade losing 45 km² from 2010-2018 (Pelto, 2018). During the 1894-1895 Alaskan Boundary Survey Yakutat Glacier ended on a flat coastal outwash plain. A decade later the glacier had retreated from the plain and a new lake was forming, Harlequin Lake. From 1906-1987 the glacier retreated ~10.5 km. From 2000-2010 the terminus area thinned ~10 m/year, the glacier retreated ~1200 m losing 5.8 km² of area (Trussel et al 2013). Here we examine Landsat imagery to quantify the retreat from 1999-2020 to identify Harlequin Lake expansion during this century.

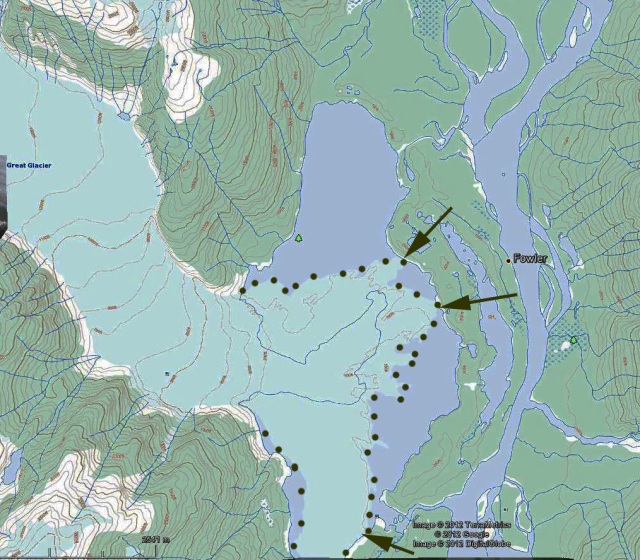

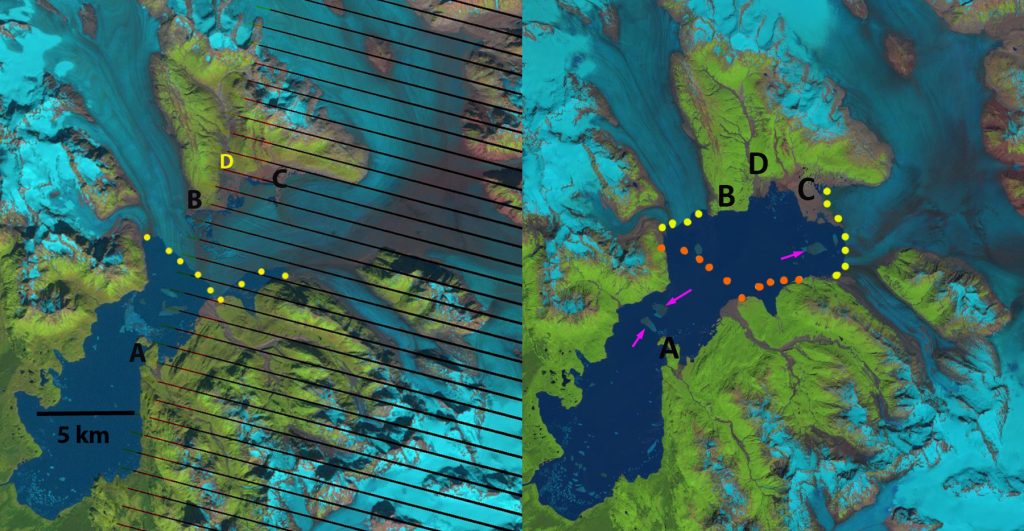

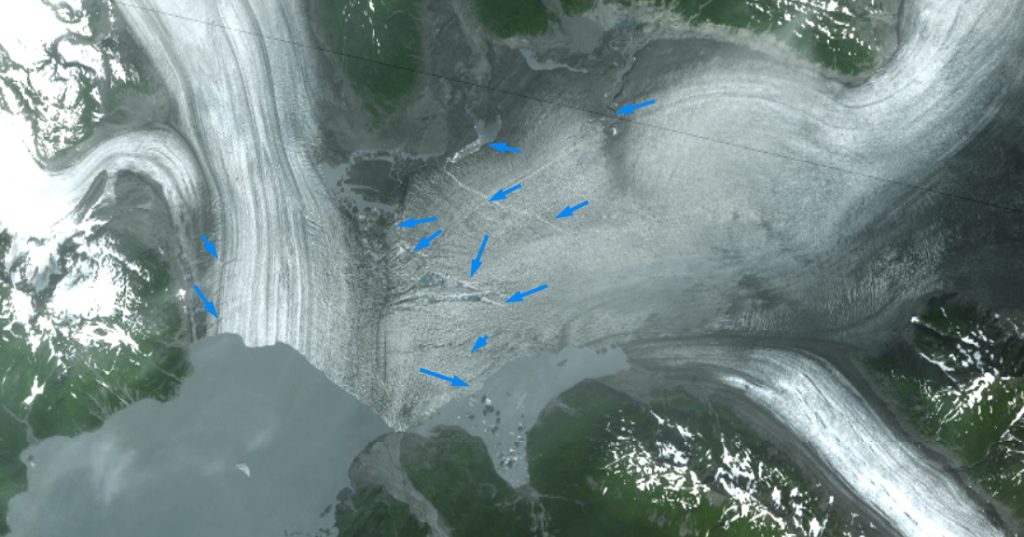

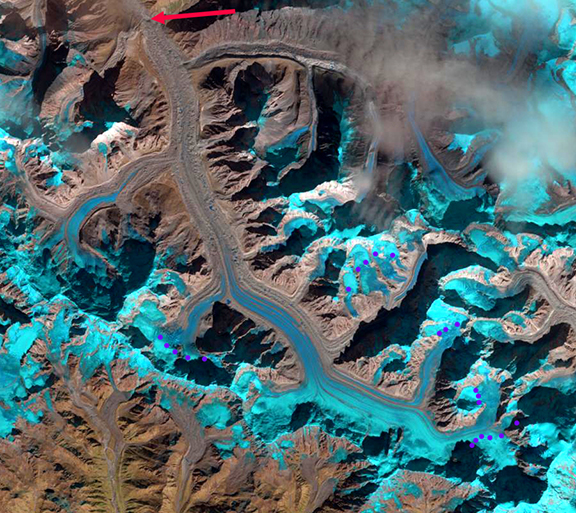

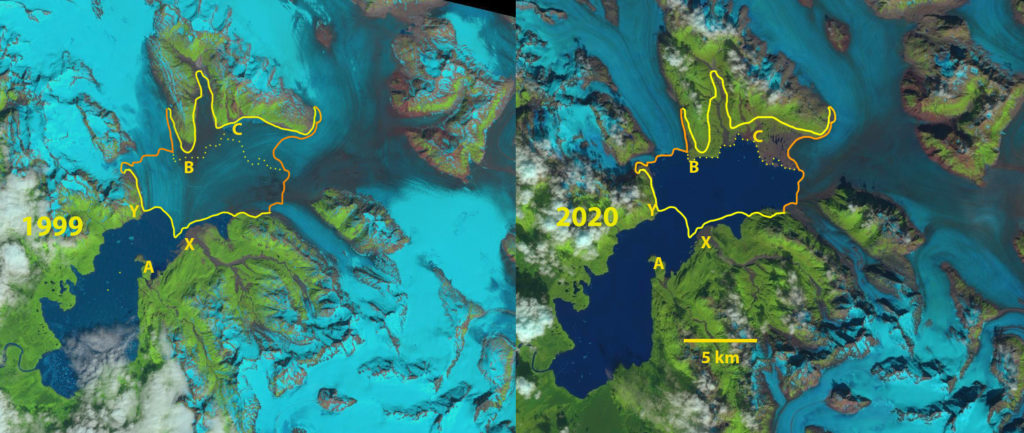

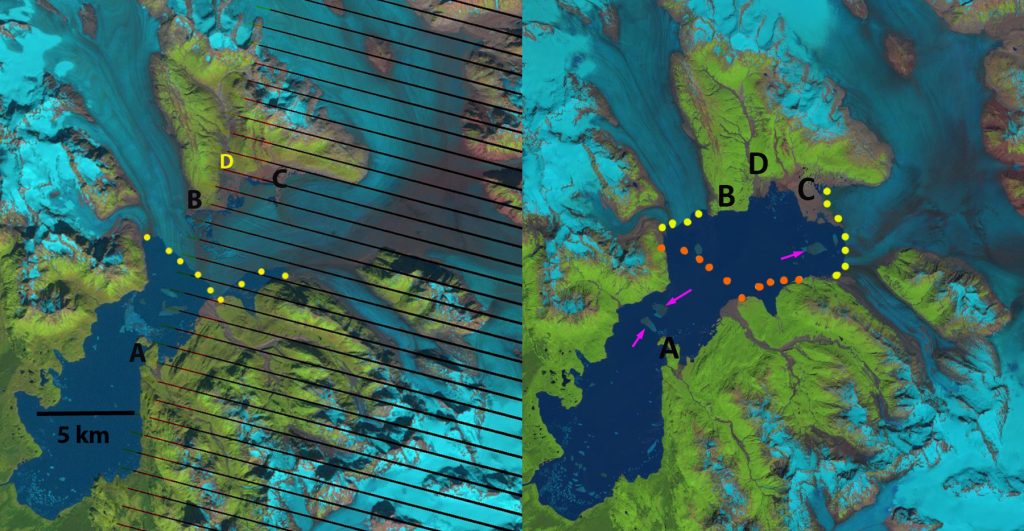

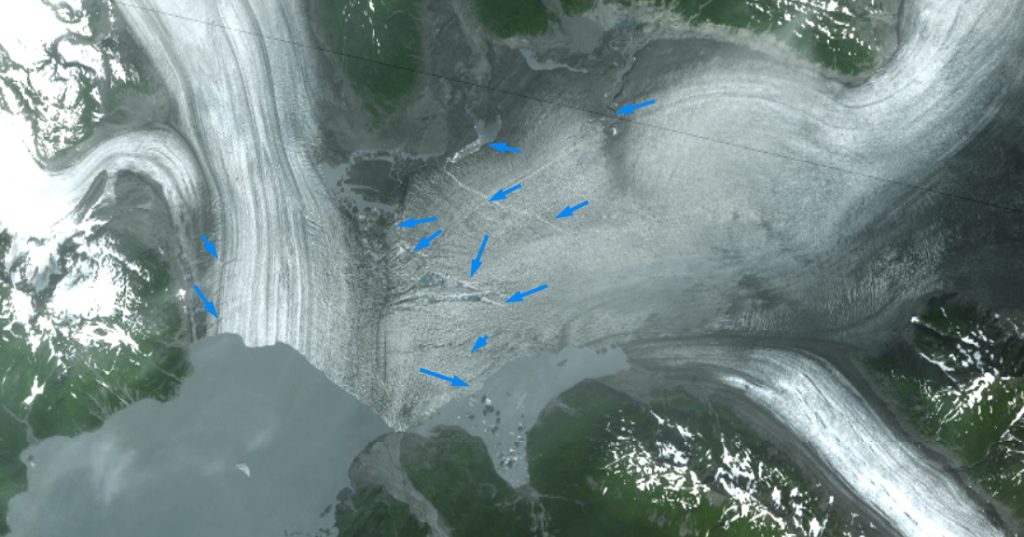

In 1999 the glacier has a single terminus extending 4.1 km across the lake from Point Y to Point X. Point B is under the glacier near the junction of the tributaries, while Point C is in the midst of the glacier. A ~1.4 km retreat up to 2010 with faster retreat on the north side and an expansion of the lake along the southern margin led to a 5.7 km long main calving front, and a 4 km long southern margin. An aerial image of the glacier in 2010 indicates significant rifting, blue arrows, that pre-conditioned the glacier for a substantial 2013 breakup. The rifts extend through the width of the glacier and typically form when thinning has led to a glacier region reaching approximate flotation (Benn, Warren and Mottram, 2007). In 2013 the glacier has separated into two separate calving fronts. The calving front extending west from Point B is 3 km wide, and the calving front extending south from Point B is 6.5 km long. There is a large area of icebergs and ice melange in front of the terminus, yellow dots in image below, resulting from the collapse. In 2015 the snowline is quite high at 2200 m, leaving very little of the glacier in the accumulation zone. In 2015 a large iceberg detached pink arrow, that is ~3.7 km², indicating continued rapid calving retreat. From 2013 to 2018 the glacier retreated from Point B to Point C on the northern side a distance of 4.6 km in five years 920 m/year. By 2018 the Peninsula extending across the lake from Point C is 2.5 km long. The terminus is resting on this and adjacent shoals across 50% of its width. The northern terminus extending west from Point B has changed little from 2013-2018. The 2018 image compares the 2010 position (yellow dots) with 2018 (orange dots) indicating an area of 45 km² lost in eight years, though not all of it is lake (Pelto, 2018; NASA 2018). The comparison of 1999 to 2020 illustrates the area of lake expansion between the 1999 (yellow) terminus position, 2020 terminus position (orange) and yellow dots along the lake shoreline. The lake area growth is 40.5 km² since 1999 with an overall area loss of ~56 km².

Landsat images from 2010 and 2018 with terminus indicated by yellow dots in both, the orange dots indicate 2010 margin on 2018 image, and pink arrows indicate icebergs.

The ability to produce icebergs as large as in 2015 has been lost as the calving front has been restricted by the Peninsula which is now 3 km long, leaving less than a 3 km wide calving front. The narrower calving front and reduced water depth should in the short term reduce retreat of the main terminus. The northern terminus is at a narrow point, as it recedes further the embayment widens and the retreat should increase.

The glacier thinned at a rate of ~4 m/year from 2000-2010 indicating how far out of equilibrium the glacier has been (Trussel et al 2013). The Yakutat Glacier does not have a high accumulation zone and the recent increase in the snowline elevation and thinning of the glacier have led to a substantial shrinking of the accumulation zone and thinning of the glacier in the accumulation (Truessel et al 2013). This glacier does not have a persistent significant accumulation zone in 2015, 2016 and 2018 and 2019 cannot survive (Pelto, 2010; NASA 2018).

2010 image of the Yakutat Glacier terminus reach with blue arrows indicating rifts.

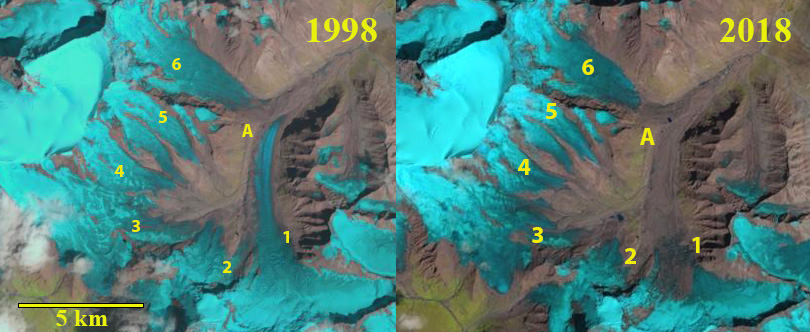

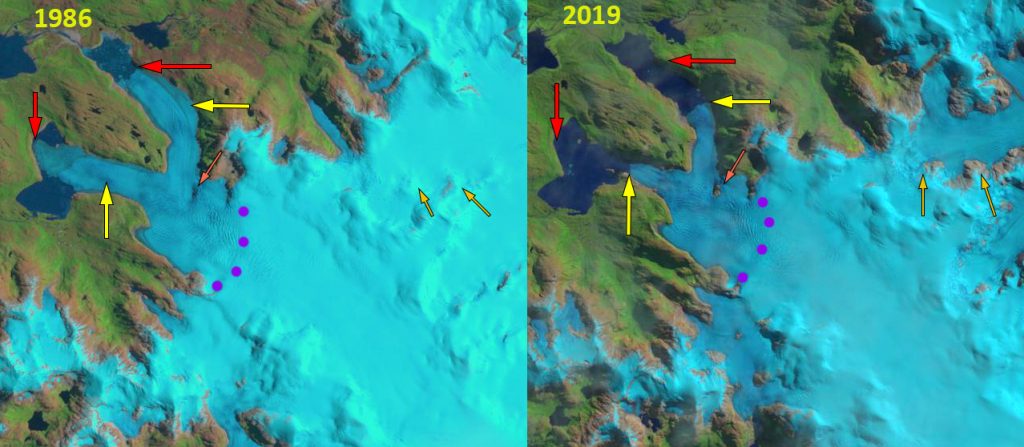

Yakutat Glacier in 2013 Landsat image.

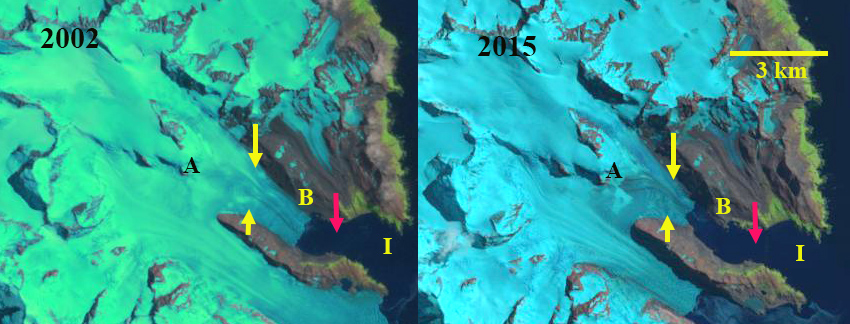

Yakutat Glacier in 2015 Landsat image.