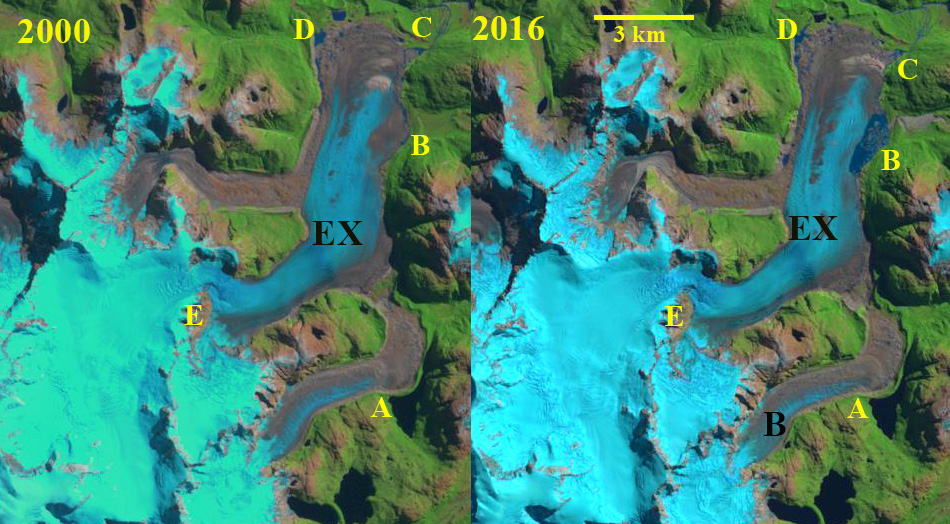

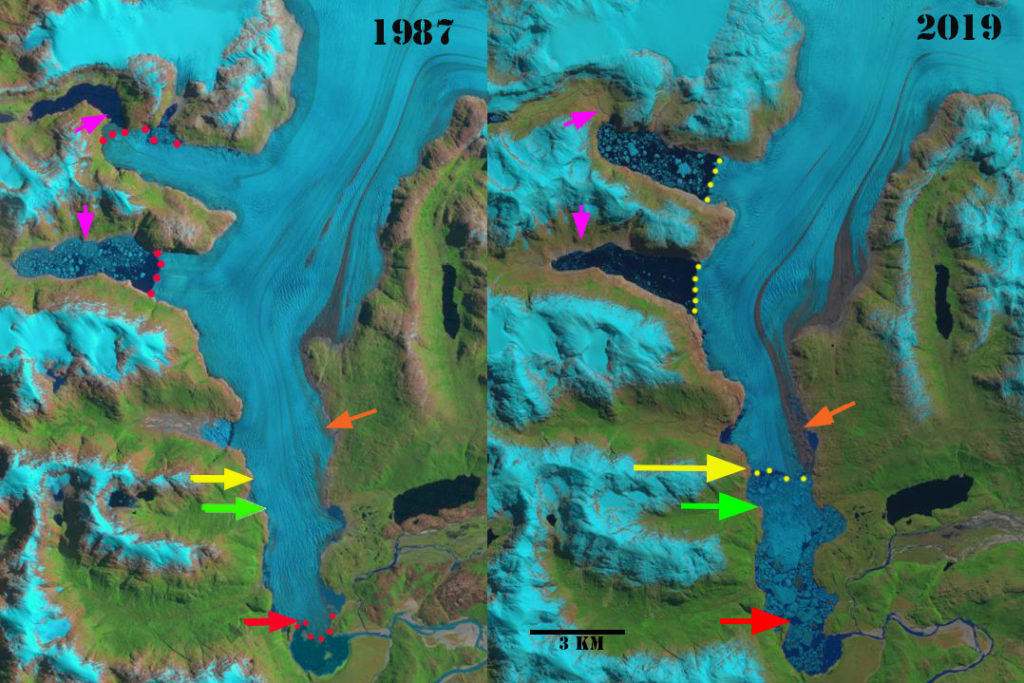

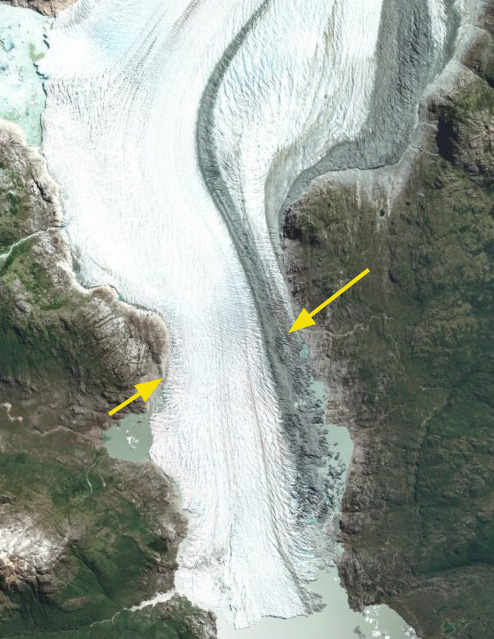

Loss of glacier connection between HPN1 and HPN2 in Landsat images from 2000 and 202o at Point A and B. Glacier tongue retreat at Point A from HPN1 and at Point C from HPN2. Formation of 1.4 km2 lake at HPN1.

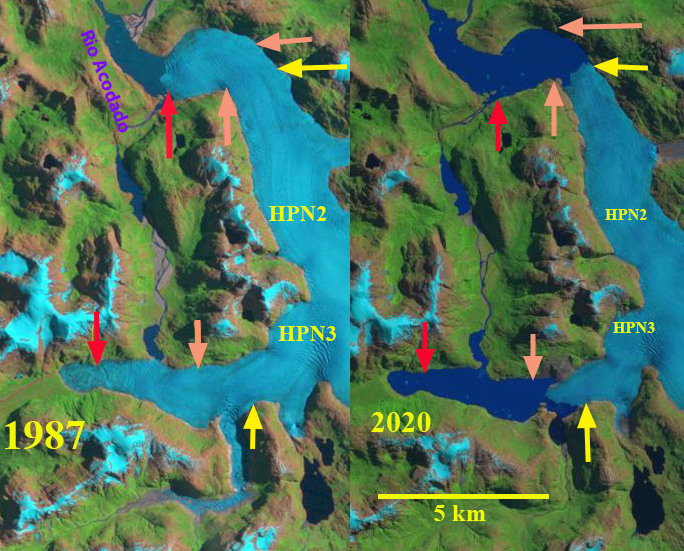

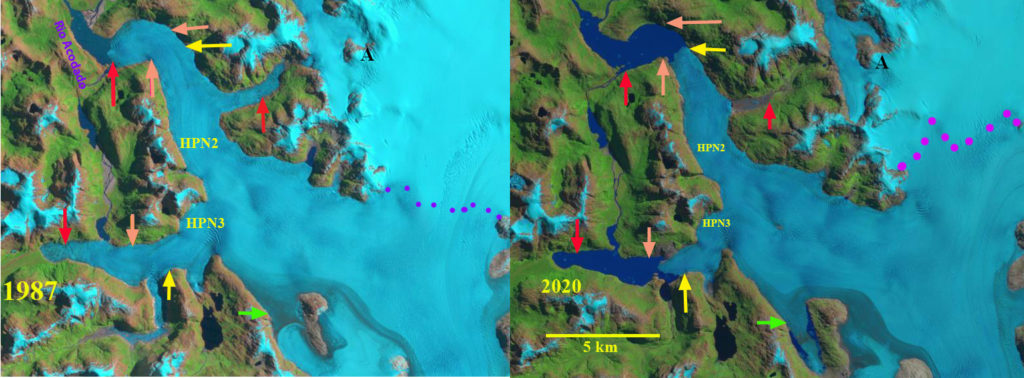

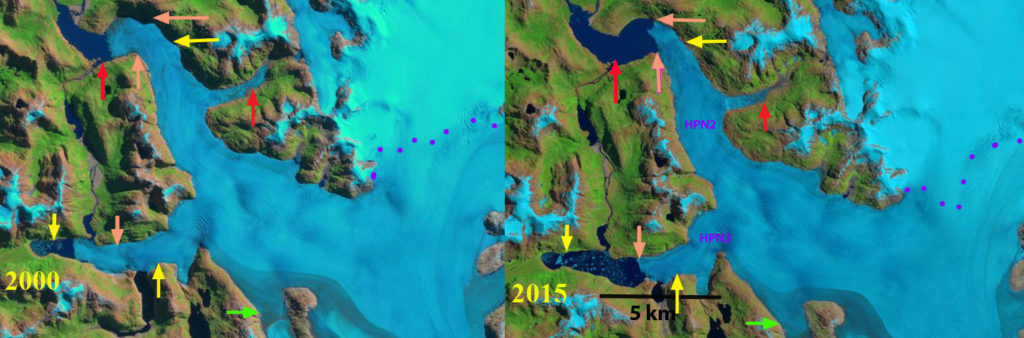

HPN1, HPN2 and HPN3 drain adjacent sections of the the Northern Patagonia Icefield (NPI). HPN2 and HPN3 comprise the Acodado Glacier, with HPN1 being the next glacier to the north is. The lakes at the terminus of HPN2 and HPN3 were first observed in 1976 and had an area of 2.4 and 5.0 km2 in 2011, while HPN1 had no lake in 2000 (Loriaux and Casassa, 2013). Davies and Glasser (2012) noted that the Acodado Glacier termini, HPN2 and HPN3, had retreated at a steadily increasing rate from 1870 to 2011. Pelto, 2017 reported a retreat from 1987-2015 of 2100 m for HPN2 and 3200 m for HPN3. From 1987-2020 Acodado Glacier terminus HPN2 has retreated 2700 m and HPN3 has retreated 4100 m. The result of this retreat is an increase in lake area at HPN2 from 2.1 km2 in 1987 to 7.1 km2 in 2020 (Pelto, 2020). Glasser et al (2016) identified a 40% increase in lake area for the NPI from 1987-2015, and a 100 m rise in the snowline. Dussailant et al (2018) identified a mass loss rate of -2–2.4 m/year for HPN1, with thinning of over 4 m/year in the lower reaches in the vicinity of Point A and B. Here we examine the impact of the rising snowline, increased melt and resultant thinning on two glacier tongues that connected HPN1 to the accumulation zone region of HPN2 in 2000 and are now disconnected.

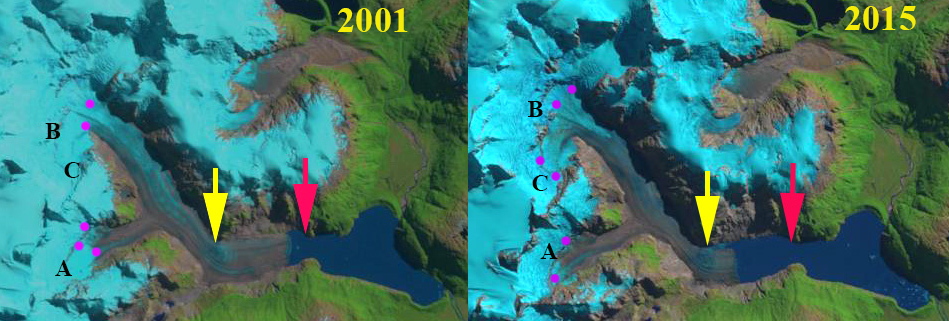

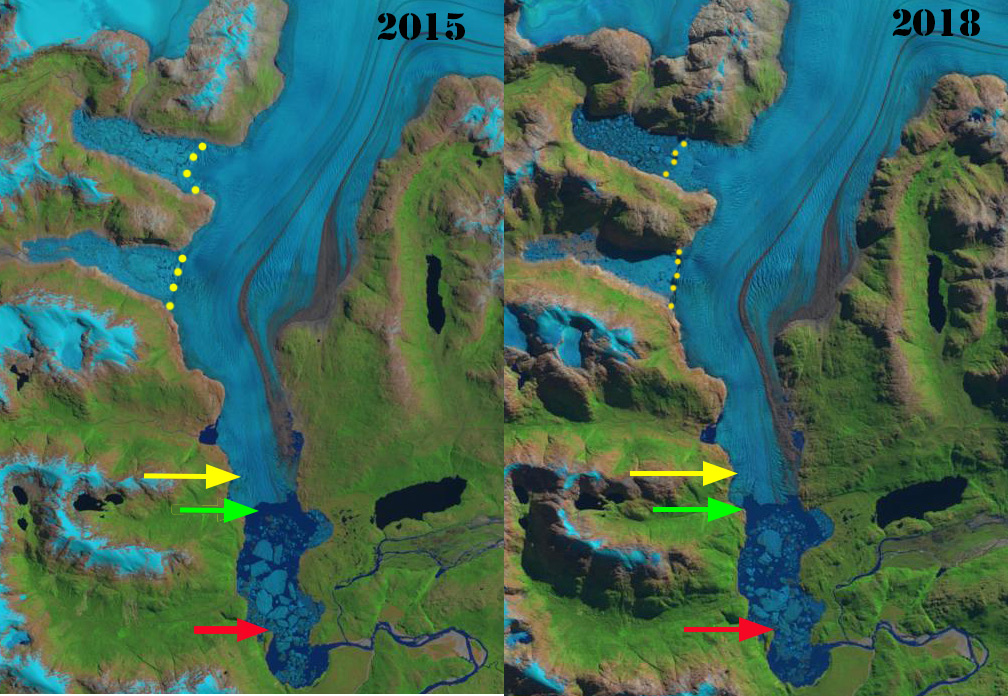

In the 2000 Landsat image glacier tongues extending from the accumulation zone region of HPN2 connect with HPN1 at Point A and Point B. At Point C an ice tongue extends 2.7 km upvalley from HPN2. By 2016 there is a disconnection at Point A with ice flowing south from HPN1 no longer joining the north flowing tongue. Point B is still connected. At Point C the ice tongue extends 1.8 km upvalley. By 2020 the connection at Point B has also been severed. At Point A ice no longer flows south into the valley from HPN1 and there is a 3.25 km long deglaciated valley between the two formerly connected ice tongues. At Point C the ice tongue from HPN2 has also been lost, a 2.7 km retreat. From 2000-2021 HPN1 has retreated 1.8 km leading to the formation of a 1.4 km2 lake. We can anticipate the rapid retreat of the glacier tongue from HPN1 at Point B during this decade. There is potential of short term formation of glacier dammed lakes at Point A and C now, and Point B in the future. There is not a hazard from drainage of these lakes that both reach tidewater via Rio Acodado within 15 km.

Loss of glacier connection between HPN1 and HPN2 in Landsat images from 2016 and 2021 at Point B. Glacier tongue retreat at Point A from HPN1 and at Point C from HPN2. Expansion of 1.4 km2 lake at HPN1.

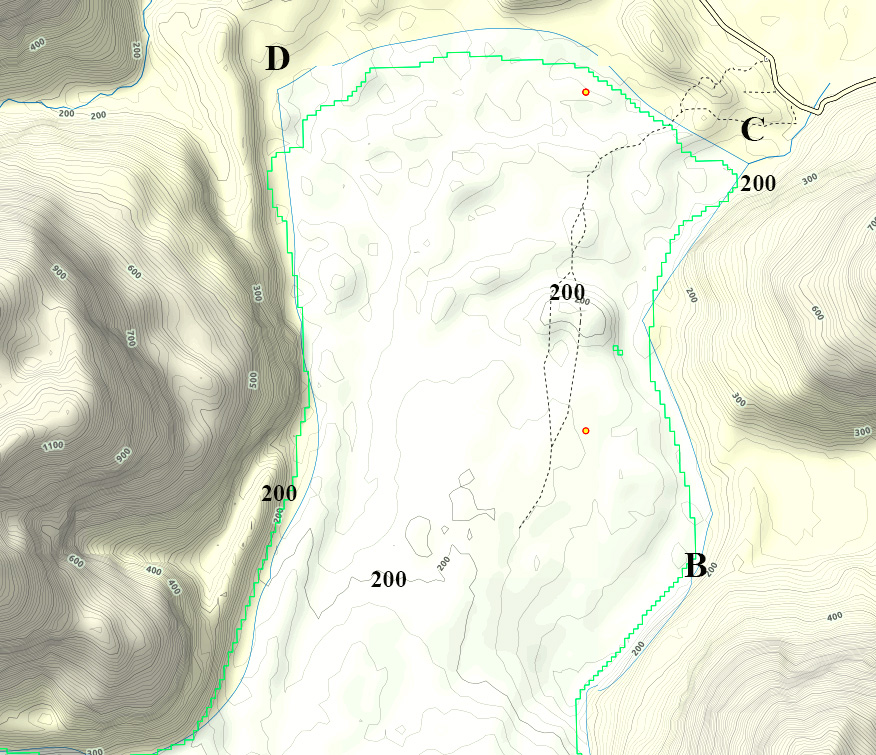

HPN1 in Sentinel 2 image from Nov. 9, 2021 illustrating the 1.4 km2 lake at HPN1 that has formed this century and the deglaciated valley at Point A.