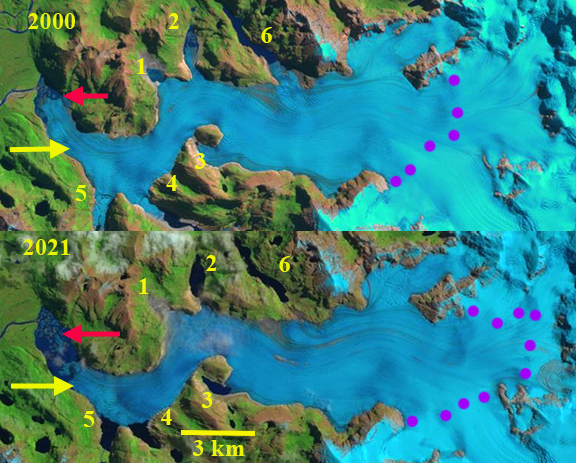

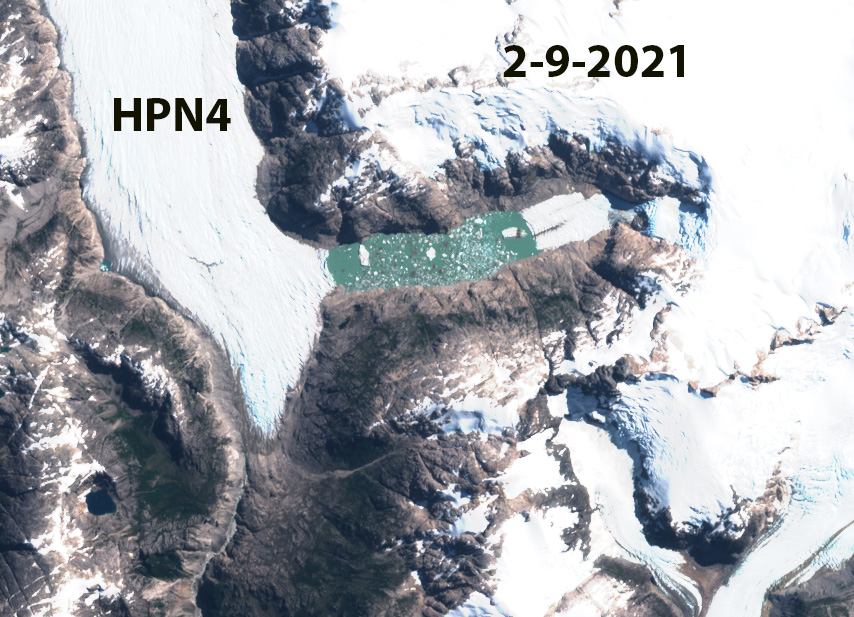

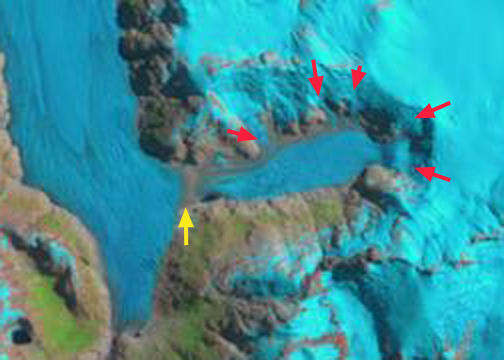

Grasshopper Glacier, Connie Glacier, J Glacier and Sourdough Glacier in 1966 map (black outline of glaciers) and in 2022 false color Sentinel image (green dots for glacier outline). The area of Grasshopper Glacier declined from 3.28 km² to 0.81 km². Closeup of area in 2021 and 2022 illustrates the many glacier fragments.

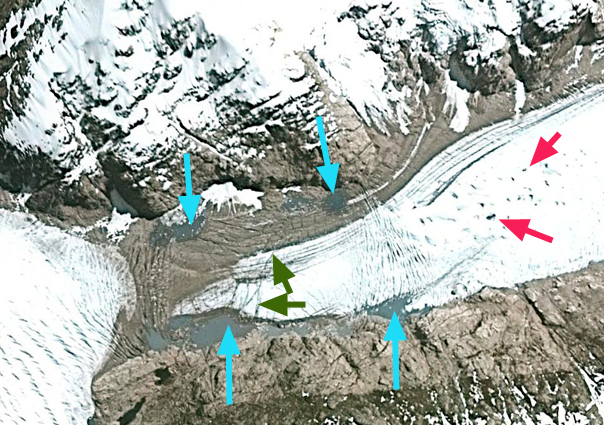

Grasshopper Glacier in the Wind River Range of Wyoming has a southern terminus calving into a lake, and a northern terminus. The southern terminus is calving and retreating expanding the unnamed lake it terminates in and retreated 350 m from 1966-2006 (Pelto, 2010). The northern terminus retreated 730 m from 1966-2006 the most extensive retreat in the Wind River Range. (Pelto, 2010). The main accumulation area on the west side of the glacier has become segmented by large bare rock areas as noted by comparing the 1966 map and 2006 image. The area declined from 3.28 km² to 2.34 km², a 27% decline (DeVisser and Fountain, 2015). Thompson et al (2011) noted a 38% loss in area of the 44 Wind River Range glaciers from 1966-2006. Maloof et al (2014) noted an even larger drop in volume of 63% of the same glaciers from 1966-2012.The combined retreat of the two terminus is over 1000 m is 26% of its 1966 length of 3.8 km. In 2006 it was clear that the significant thinning and marginal retreat at the head of the glacier was symptomatic of a glacier that would disappear with current climate. Here we return to examine how this glacier has fared particularly in the exceptionally warm summers of 2021 and 2022 using false color Sentinel images and comparison with the 1966 map.

In 2021 and 2022 the glacier was nearly snowless by the end of August, this resulted in significant thinning and marginal recession. In 2021 and 2022 there are six glacier fragments with remaining glacier ice that are no longer connected to the glacier. In 2022 the glacier area has declined to 0.81 km², a 75% loss in area since 1966 and a 66% loss since 2006. The overall length from the north to south terminus is now 2.1 km in 2022. What is leading to the rapid area loss is the lack of avalanche accumulation on this glacier and increased summer temperatures, leading to additional ablation. The length is declining less than the area, because the central axis of the glacier has the thickest ice. Because the glacier in many years such as 2021 and 2022 has retained no snowpack, and any snowpack that had been retained in other years, as firn, has also been lost, the glacier no longer has an accumulation zone. With current climate it still will disappear. This is the same forecast as for most Wind River Range glaciers, such as Sacagawea and Mammoth.

Grasshopper Glacier in September 2021 and 2022 false color Sentinel images. Separated glacier fragments numbered 1-6.

Google Earth image with outline of glacier in 2006 and 1966 map outline in orange.

Grasshopper Glacier southern terminus in 2012 Sarah Meiser image.