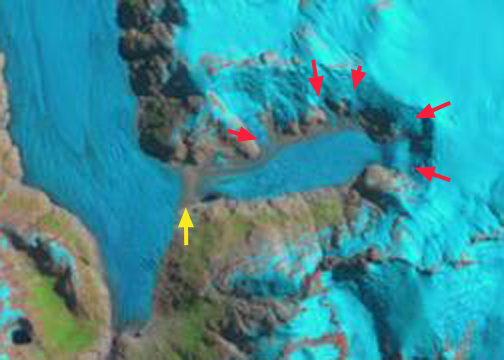

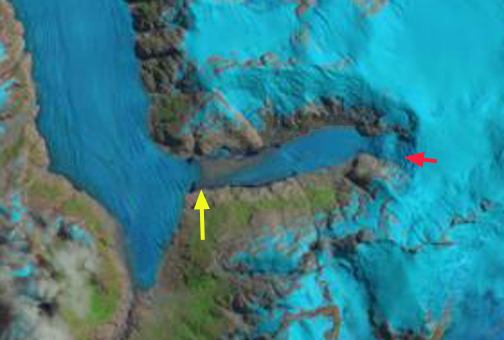

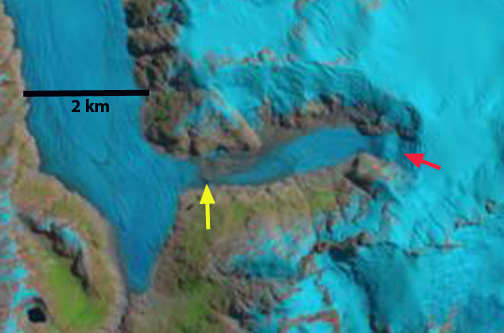

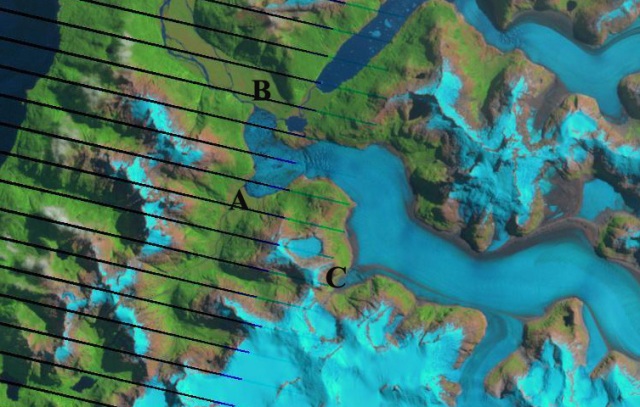

Soler Glacier, Chile terminus tongues is 1.9 km long on 12-26-2022 and by 3-21-2023 it has broken up, with four larger bergs A-D. False color Sentinel images.

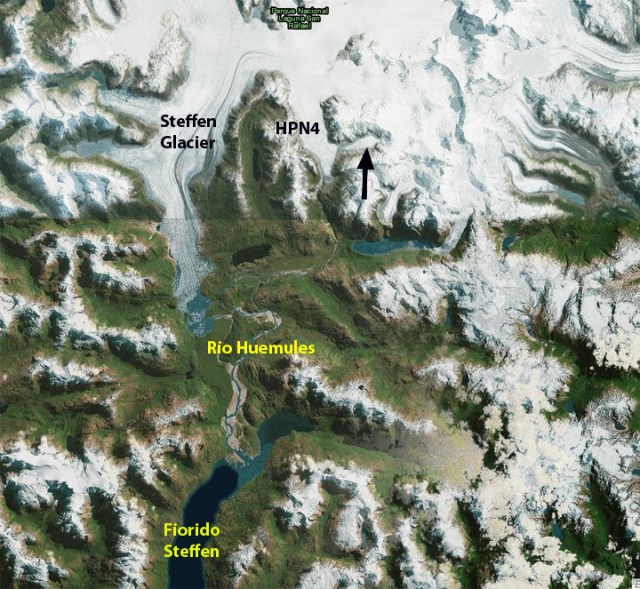

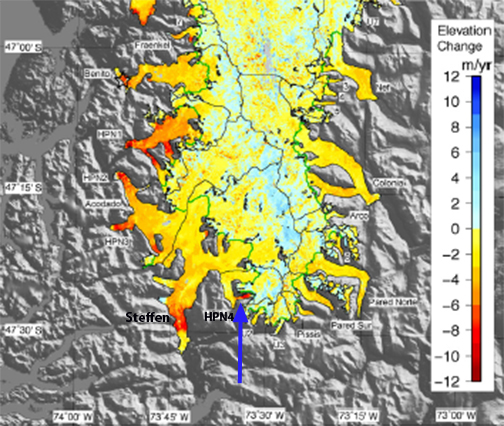

In 2020 I noted that the Soler Glacier “terminus tongue in its lowest 1.5 km continue to thin and will collapse in the lake in the near future.” Here the breakup of this tongue in 2023 is reported. Soler Glacier is an outlet glacier on the east side of the Northern Patagonia Icefield (NPI). The terminus response of this glacier was slower and more limited than on most NPI glaciers, just 200-350 from 1944 to 1984 (Aniya and Fujita 1986). Glasser et al (2016) note the recent 100 m rise in snowline elevations for the NPI, which leads to the 2 m thinning per year identified by Willis et al, (2012) in the ablation zone from 1987-2011. Loriaux and Casassa (2013) examined the expansion of lakes on the Northern Patagonia Ice Cap reporting that from 1945 to 2011 lake area expanded 65%, 66 km2.

Soler Glacier had no proglacial lake in 1987. By 2000 a small lake had developed both on the north and south side of the main terminus with a total area of ~0.3 km2 see Mike Hambrey image below. In 2016 lake had expanded, with the northern arm mostly filled with ice.For Soler Glacier lake formation did not occur until the last decade reaching an area of 1 km² by 2020. As the 2022/23 melt season began the glacier had a 1.9 km long central tongue extending down the middle of the lake, that had an area of 1.4 km², as evidenced on Dec. 26, 2022. By early March the tongue had broken up as revelaed by the Sentinel image on March 21, 2023. On this date the lake surface has refrozen on the south side and has some new snow on it. The lake has expanded to 2.75 km², with the largest iceberg B, occupying 10% of the lake. The lake expansion is small compared to Steffen Glacier or San Quintin Glacier, but just as significant for this smaller glacier.

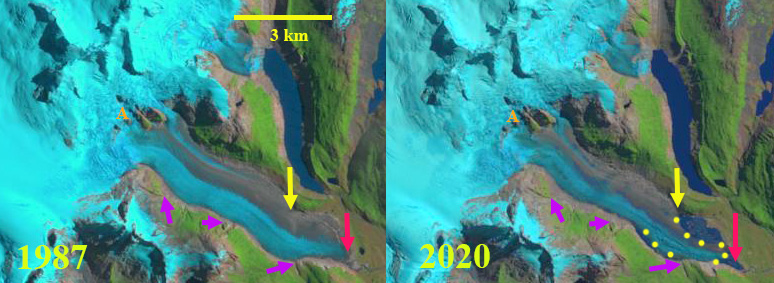

Soler Glacier in 1987 and 2020 Landsat images. Red arrow indicates 1987 terminus location, yellow arrow indicates 2020 terminus location on north side of glacier. Yellow dots indicate margin of lake and purple arrows indicate specific locations where glacier thinning is evident.

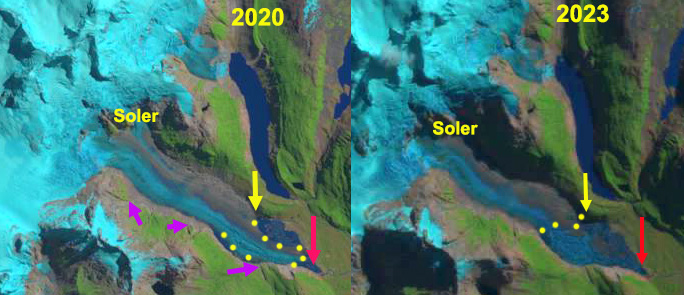

Soler Glacier in 2020 and 2023 Landsat images. Red arrow indicates 1987 terminus location, yellow arrow indicates 2020 terminus location on north side of glacier. Yellow dots indicate margin of lake and purple arrows indicate specific locations where glacier thinning is evident in 2020.

Mike Hambrey Photograph of Soler Glacier in 2000, illustrating narrow nature of the proglacial lake.

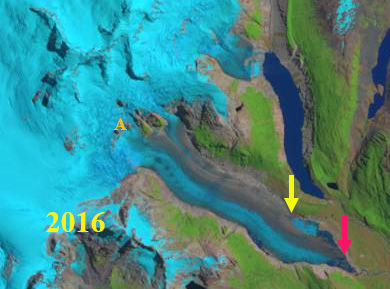

Soler Glacier in 2016 Landsat image. Red arrow indicates 1987 terminus location, yellow arrow indicates 2020 terminus location on north side of glacier. Lake area is still limited.