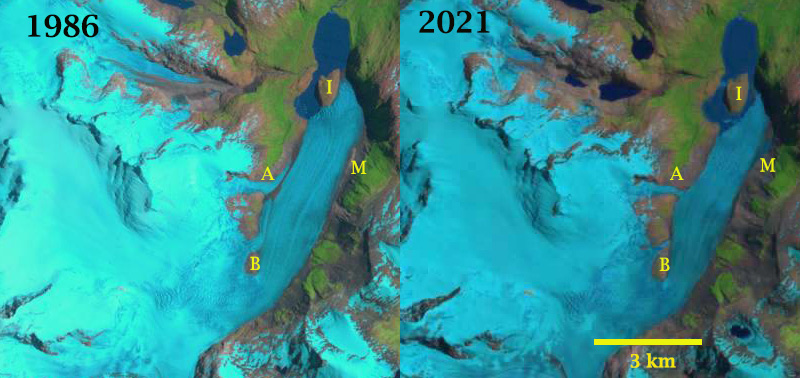

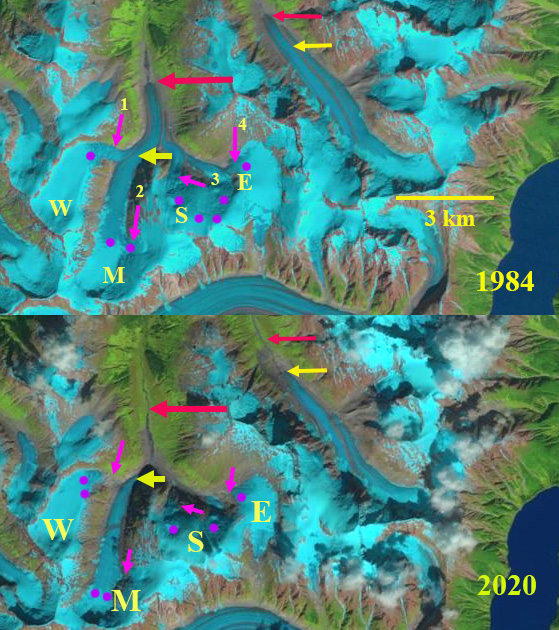

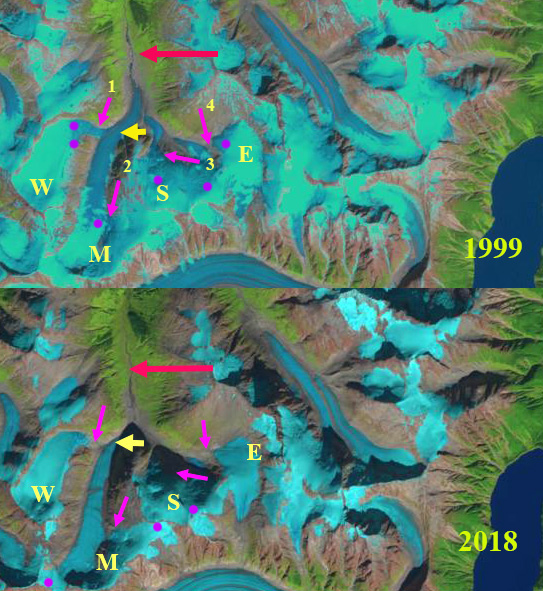

Oriental Glacier in 1986 and 2021 Landsat imagery illustrating retreat from the island (I) and diminishing width and flow of tributaries at P0int A and B. A marginal lake has formed at Point M as the glaciers terminus section has thinned and narrowed.

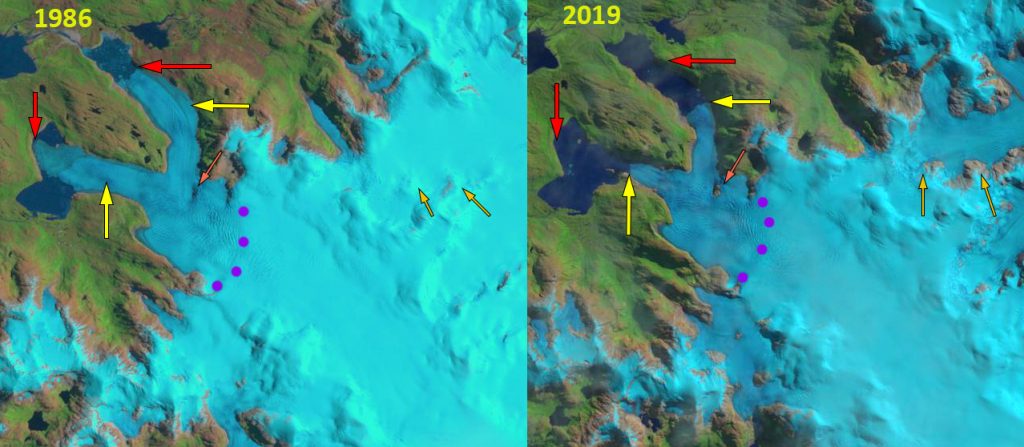

Oriental Glacier terminates in an expanding proglacial Lago Oriental at the northeastern margin of the Southern Patagonia Icefield (SPI). The glacier had terminated on an island in this lake for several decades until 2019. In this region glaciers thinned ~0.5 m/year from 2000-2012 with Oriental Glacier thinning 0.5-1.0 m/a (Falaschi et al 2017).. Mouginot and Rignot (2014) identified a velocity peak at 1 km/year extending from the Cerro Azul (3018 m) eastward to the northward terminus bend. Oriental Glacier had a slower retreat than most SPI glaciers from 1870-2011 at 0.1-0.15 km/a, and the fastest rate from 2001-2011 Davies and Glasser (2012). Here we examine Landsat imagery from 1986 to 2021 to illustrate glacier changes and Sentinel imagery from 2020 and 2021 illustrating island separation and retreat acceleration.

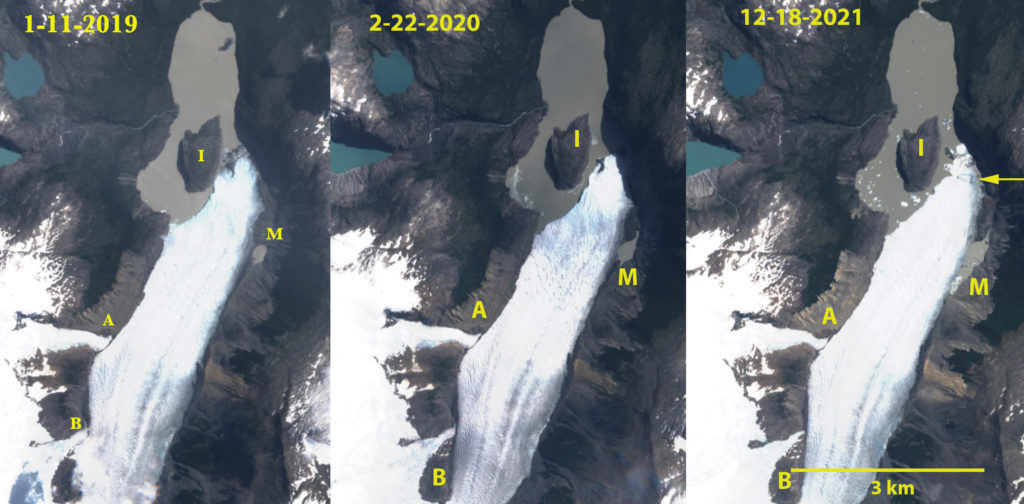

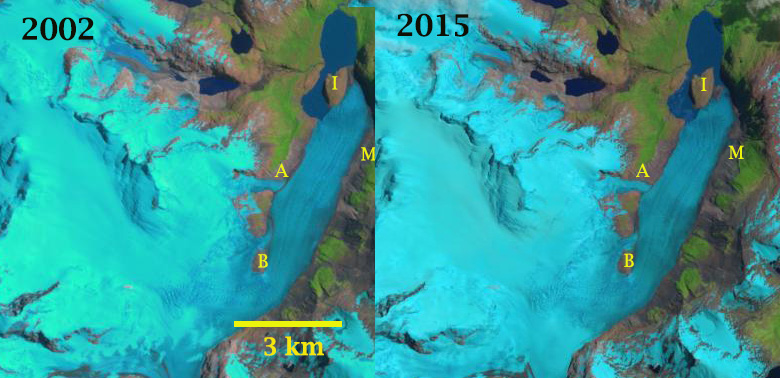

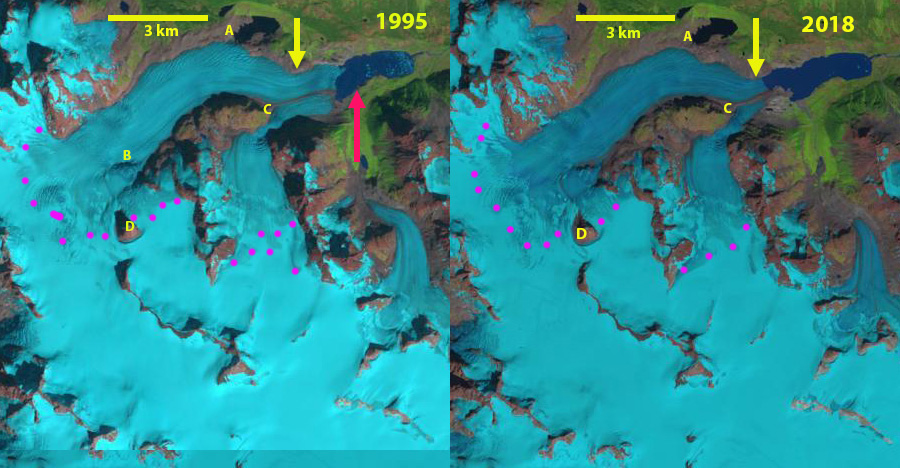

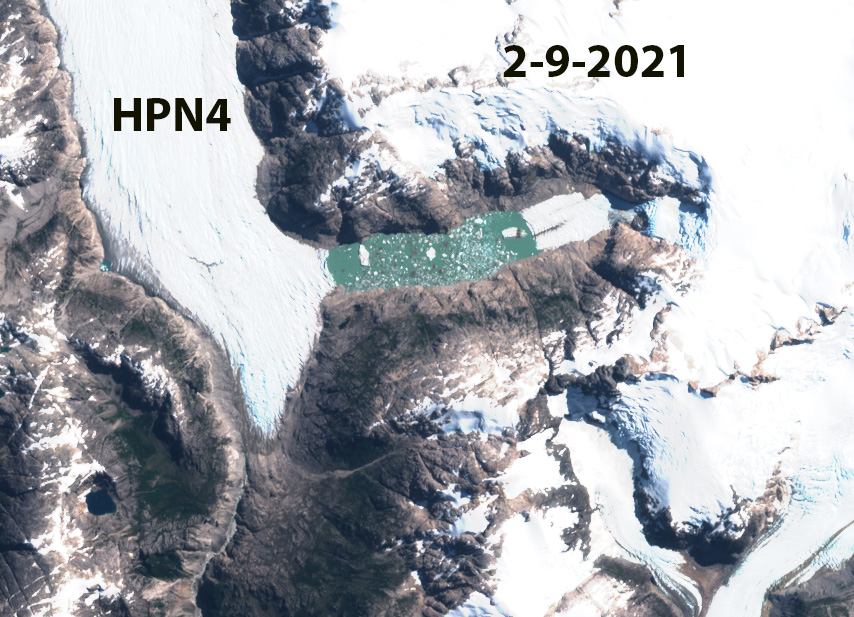

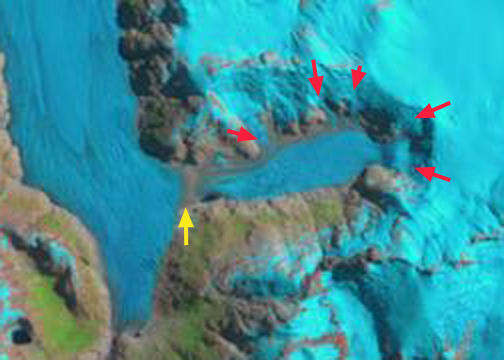

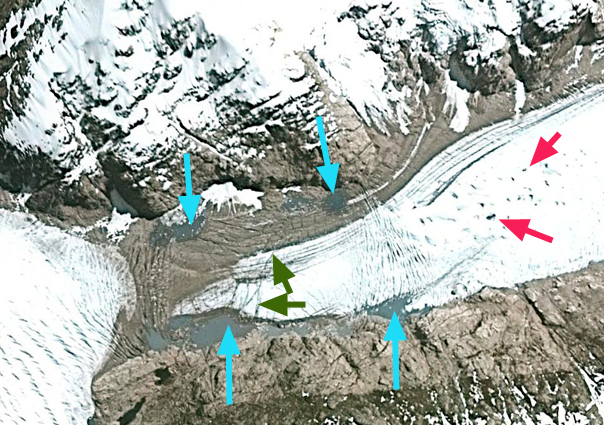

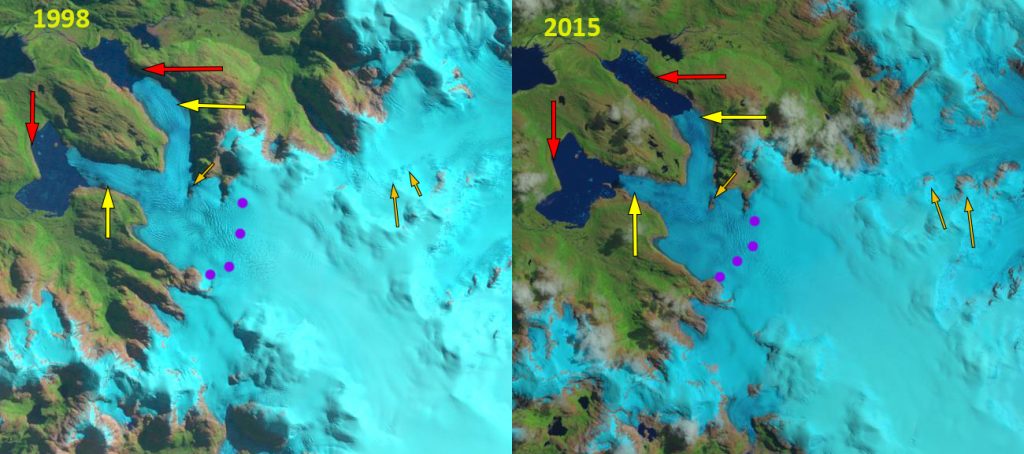

In 1986 the glacier terminates on the island with a small proglacial outwash plain in front of the eastern tongue, marginal connection is 1.5 km long. Tributary A and B are both significant contributors to the terminus tongue. At Point M the glacier is 1.75 km wide. The surface slope of the lower 6 km of the glacier in from 1986-2002 is ~4-5%, this is a low surface slope, suggesting this section of the glacier occupies a basin, a continuatin of the current Lago Oriental. In 1998 there is little evident change. By 2002 the glacier connection to the island has a similar length, but the ice is thinner than in 1986. In 2015, tributary A and B are narrower, contributing less ice to the terminus region. The connection to the island is reduced to ~1 km, while the proglacial outwash plain is still similar in size. In January of 2019 the connection to the island is almost gone and the proglacial outwash plain is significantly reduced. The marginal lake is ~0.05 km2. By February of 2020 the connection to the island has been lost and the marginal lake has expanded to 0.1 km2. In 2021 the glacier has retreated 150 m from the island and a rift has formed that will lead to a signficant calving event ~0.125 km2, probably this summer. The marginal lake has expanded to 0.2 km2 . Tributary B has essentially separated from the main glacier in 2021.

Calluqueo Glacier retreat and Lucia Glacier retreat have been significantly larger; however, Oriental Glacier is poised for a rapid retreat and lake expansion. The lake basin likely extends at least 5 km from the present terminus. At that point Lago Oriental would be 9 km long.

Oriental Glacier terminus reach in 2019, 2020 and 2021 Sentinel 2 imagery illustrating retreat from the island (I) and expansion of the marginal lake at Point M. Note tributary B has essentially disconnected in 2021. A rift is forming at yellow arrow, poised for a calving event this summer.

Oriental Glacier in 2002 and 2015 Landsat imagery illustrating connection remaining to the island (I). A small marginal lake has formed at Point M as the glaciers terminus section has thinned and narrowed.

Oriental Glacier in 1998 Landsat image and topographic map of area. Elevation contours indicates low slope of termius reach from 600 m to terminus. Blue arrows indicate glacier flow.