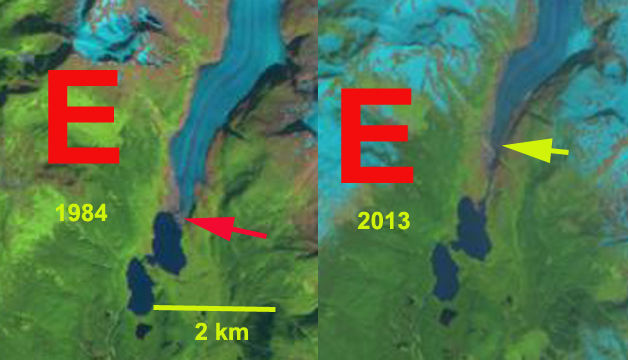

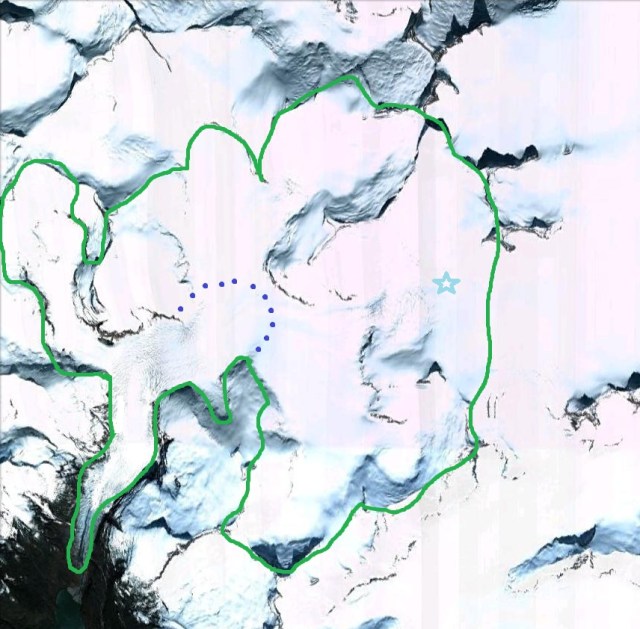

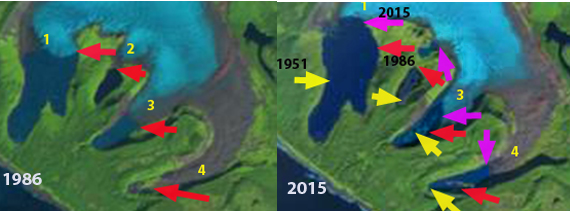

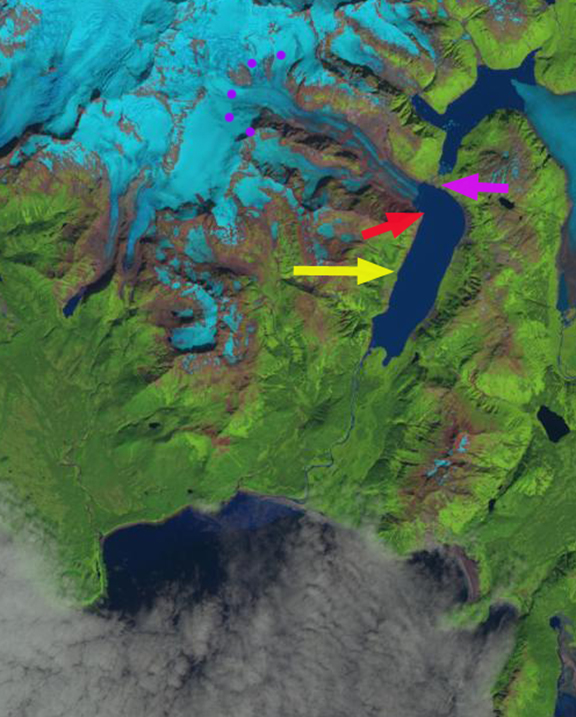

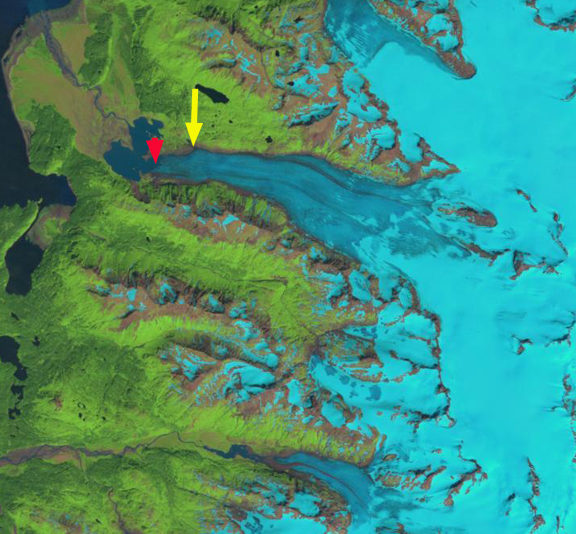

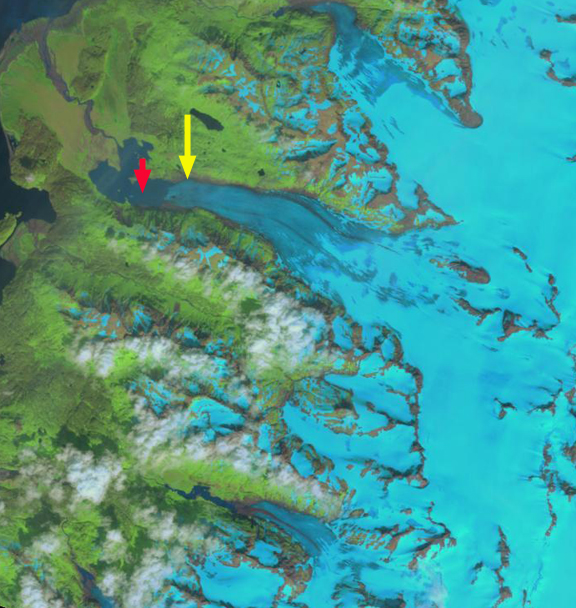

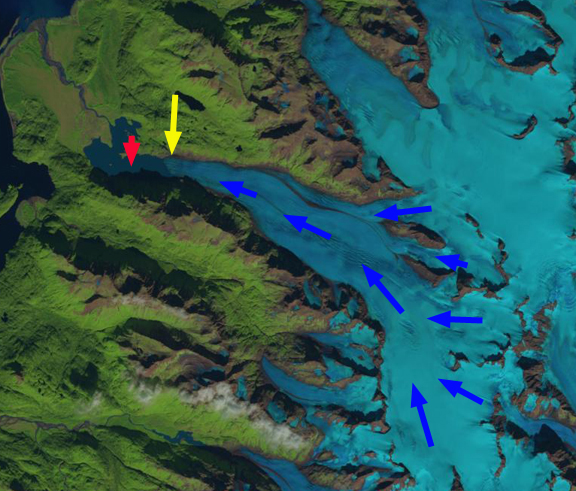

McBride Glacier (M), its secondary terminus (Ms), MCbride Inelt (MI) and Riggs Glacier (R) in Landsat image comparison from 1985 and 2015. The red arrows indicate the 1985 terminus location and the yellow arrows the 2015 terminus location. Main terminus 4.4 km retreat, secondary terminus 2.7 km retreat.

McBride Glacier was part of the Muir Glacier complex in Glacier Bay, Alaska, until the 1960’s when it separated from Muir and adjacent Riggs Glacier. Riggs Glacier and Muir Glacier are no longer calving tidewater glaciers, while McBride has continues to terminate in a tidewater inlet. Riggs Glacier’s retreat from the sea was complete by 2009.The continued rapid retreat of McBride Glacier is enhanced by calving. Calving generates icebergs, the number of icebergs has had a direct relationship with number of harbor seals. The number of harbor seals observed has declined substantially in Glacier Bay since 1993 (Glacier Bay NPS). In particular the population has declined in front of Muir Glacier which no longer calves, while a smaller population has remained in front of McBride Glacier (Womble et al, 2010). Here we examine Landsat imagery from 1985 to 2015 to quantify the retreat and estimate how long until this glacier too will no longer calve.

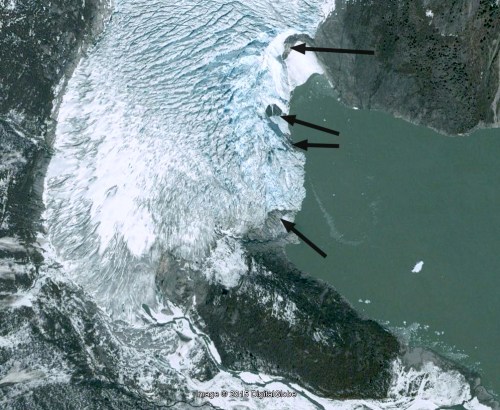

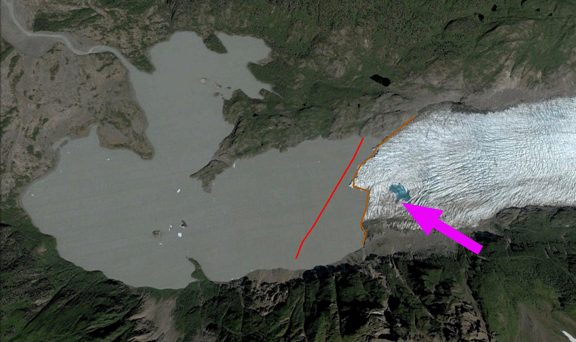

Inn 1985 the main glacier terminated 1.3 km from Muir Inlet, with a narrow connecting stream to Muir Inlet. The secondary terminus extended west down a separate valley, 3.75 km from the main glacier nearly reached the Riggs Glacier. The snowline was at 900 m. By 1996 the main terminus had retreated 1.1 km, and the connection with Muir Inlet had expanded to 200 m. The secondary terminus had narrowed but still nearly reached Riggs Glacier. There are two tributaries from the east at purple arrows connected to main glacier. By 2013 the glacier has retreated an additional 2.0 km and reached a northward turn in the inlet, The secondary terminus had mostly disappeared extending only 1.25 km from the main glacier. The eastern tributaries, purple arrows, had both retreated and detached from main glacier. By 2015 the glacier had retreated 4.4 km since 1985 including 1.3 km since 2013. The glacier now terminates at the head of a 6 km long inlet. The glacier is still actively calving, which is good for the harbor seals. However, a small icefall 0.8-1.1 km from the current terminus indicates a possible location for the end of the tidewater portion of this valley, note orange arrow in Google Earth image below. The retreat of the secondary terminus has been 2.7 km during this same period, without any calving. In 2013 and 2015 the snow line was above 1000 m, which as on nearby Brady Glacier is well above the equilibrium average which will continue to drive retreat Pelto et al, 2013). In 2016 southeast Alaska has had its hottest spring, which will continue this chapter.

Counting harbor seals is a task completed by the Glacier Bay NPS, they follow two populations the larger in John Hopkins Inlet off of Glacier Bay and the other in Glacier Bay proper. Both have declined by over 80% since 1992. In 2009 there were 200 harbor seals in McBride inlet Glacier Bay NPS. Glaciers are part of the local ecosystem where they exist, glacier changes do result in broader ecosystem changes, in this case harbor seals is one monitored example. The NPS prepares annual reports on glacier change in the region and notes widespread thinning in the region since 1995 and a 15% decline in glacier area in the last half century Loso et al (2014). The team of N.Loso, A.Arendt, C Larsen, N.Murphy and J.Rich have produced annual reports in recent years with valuable detail on changes of glaciers across Alaskan National Parks.

1996 Landsat image indicating terminus positions from 1985, read arrow and 2015 yellow arrow. The purple arrow indicates tributaries attached to main glacier.

2013 Landsat image indicating terminus positions from 1985, read arrow and 2015 yellow arrow. The purple arrow indicates tributaries detached from main glacier.

2014 Google Earth image indicating the icefall in relation to 2014 terminus. The icefall has increased calving and a 100 m increase in elevation. This is certainly a location where the valley bottom rises, and may be the end of the tidewater reach of the inlet.