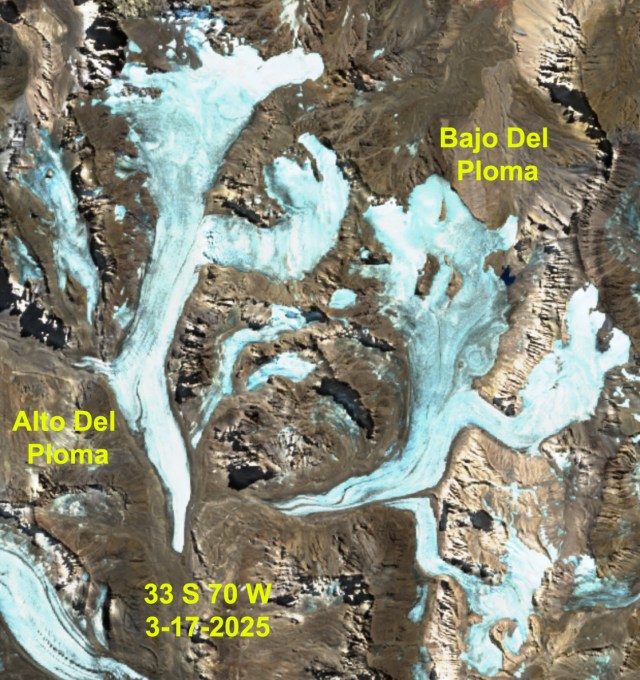

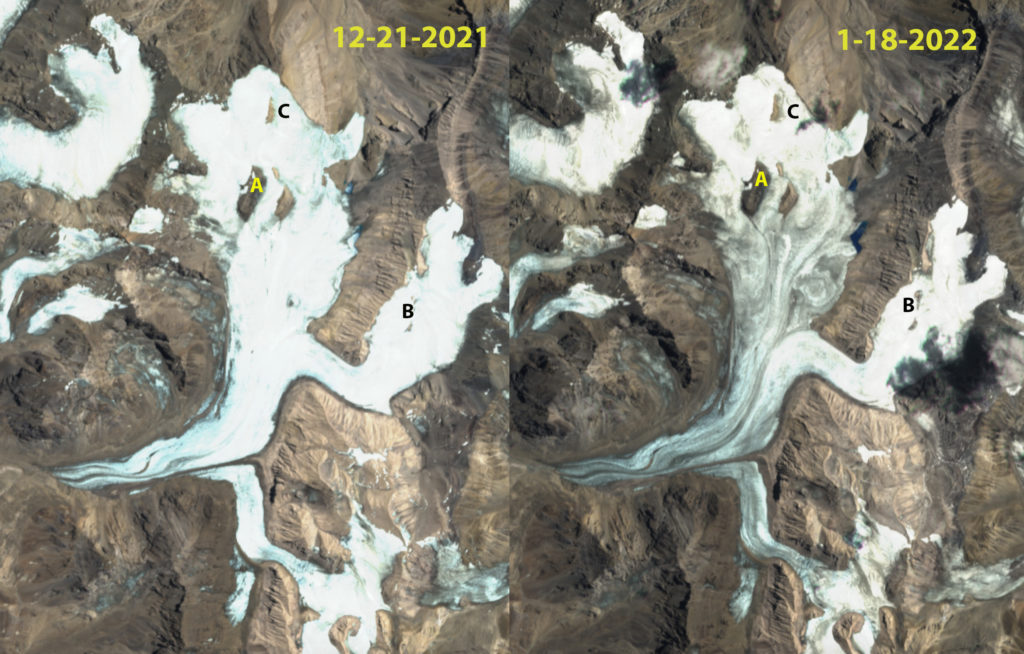

Bajo del Plomo Glacier, Argentina in Sentinel image with no retained snowcover this summer, and rapid bedrock expansion at Point A-C. This is 2nd consecutive year without retained snowcover for this glacier at the head of the Rio Plomo.

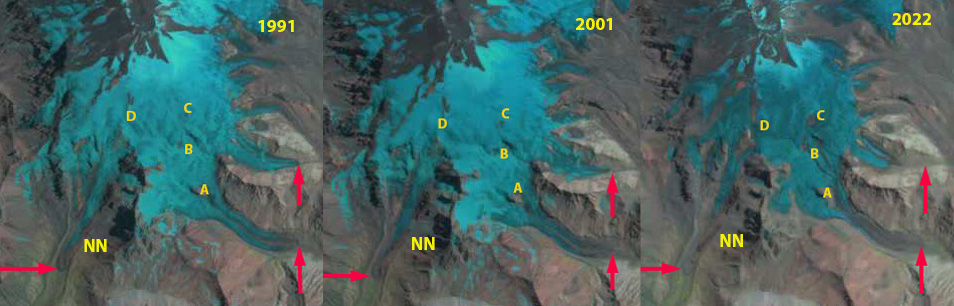

For an alpine glacier to thrive it must remain 50-60% snowcovered throughout the year, even at the end of the summer. To survive it must have consistent significant snowcover at the end of summer, indicative of a persistent accumulation zone. This year in the Central Andes of Argentina and Chile I have chronicled the near total loss of snowpack through February, leading to dirty/dark snowcover free glaciers. This is a same story we observed in 2022, though snowcover was lost in January last year (Pelto, 2022). The consecutive summers with glaciers laid bare results in significant losses. The darker bare surfaces of the glacier melt faster leading to more rapid area and volume loss. This includes fragmentation and rapid expansion of bedrock areas amidst the glacier. We saw in the Pacific Northwest two consecutive summers with limited snowcover retained. Hopefully the Central Andes region will experience a good winter much as the Mount Shasta, CA area has in winter 2023.

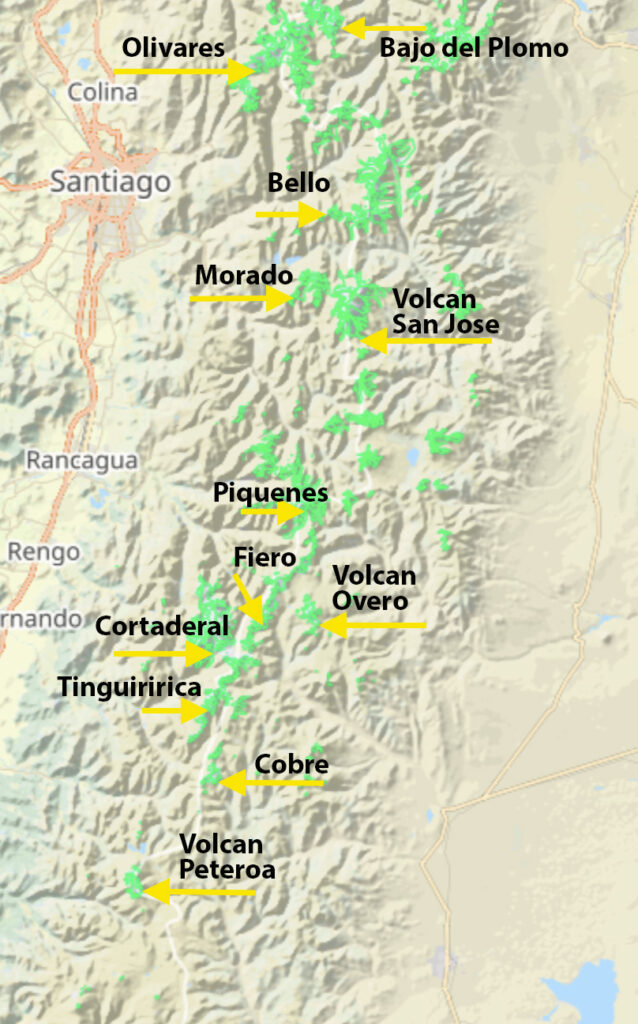

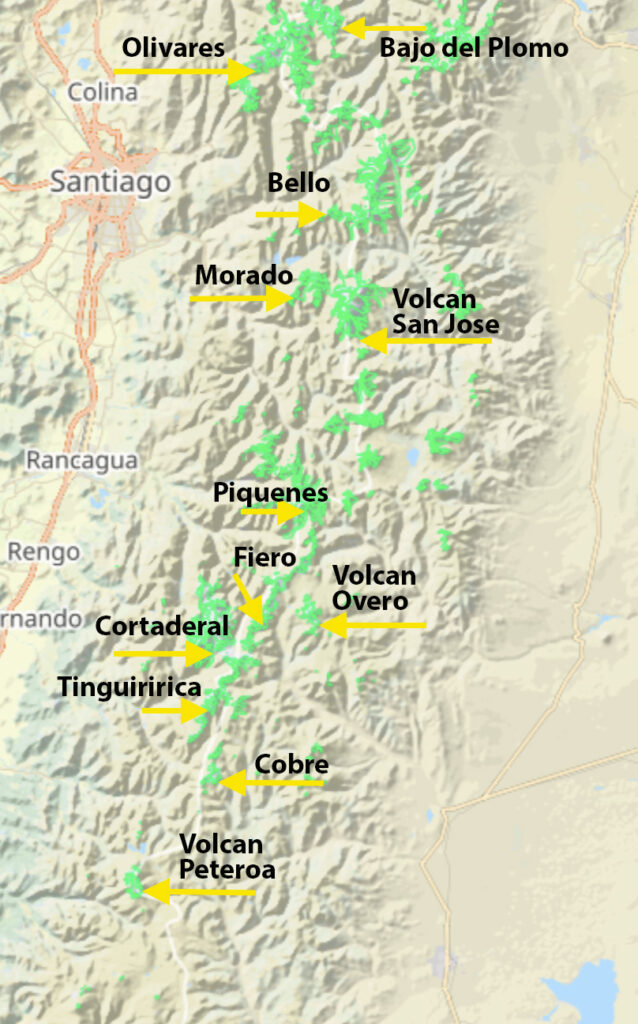

Here is an update at the end of the summer using false color Sentinel imagery to highlight a sample of these glaciers that have remained largely bare for two months. Individual posts during 2022 or 2023 include: Volcan Peteroa glaciers, Rio Atuel glaciers, Sollipulli Glacier, Palomo-Cipreses Glacier, Bajo del Plomo Glacier, Cortaderal Glacier, Volcan San Jose Glaciers , Cobre Glacier, Olivares Beta and Gamma Glaciers and Volcan Overo Glaciers,

Olivares Beta and Gamma Glacier, Chile in Sentinel image with no retained snowcover this summer, retreating away from proglacial lakes and bedrock expansion. This is 2nd consecutive year without retained snowcover for these glaciers.

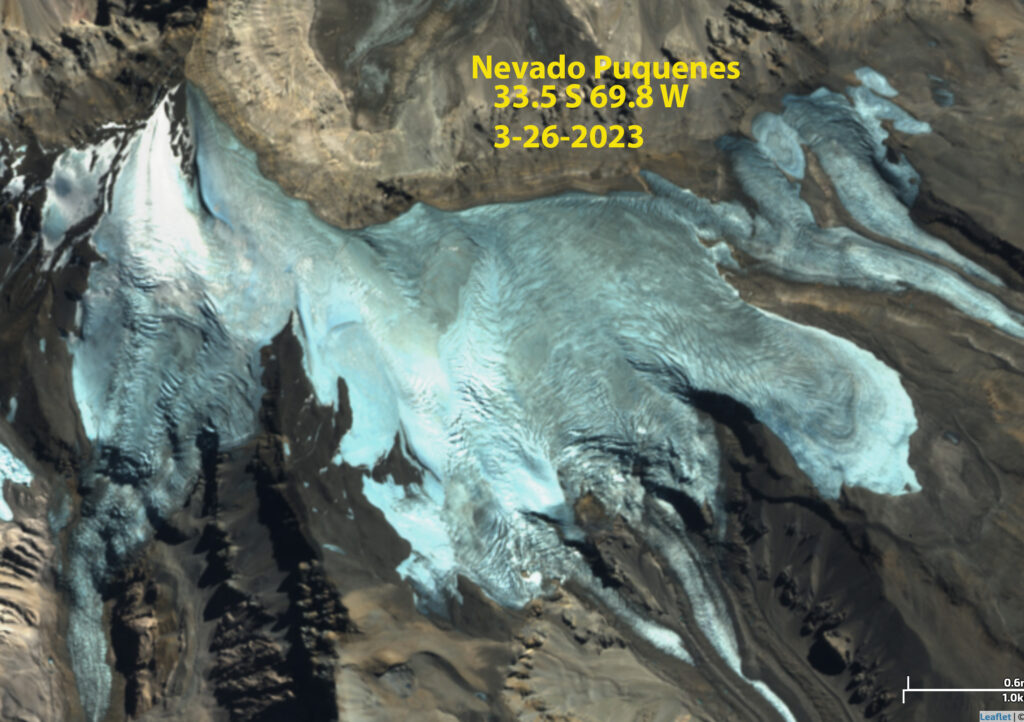

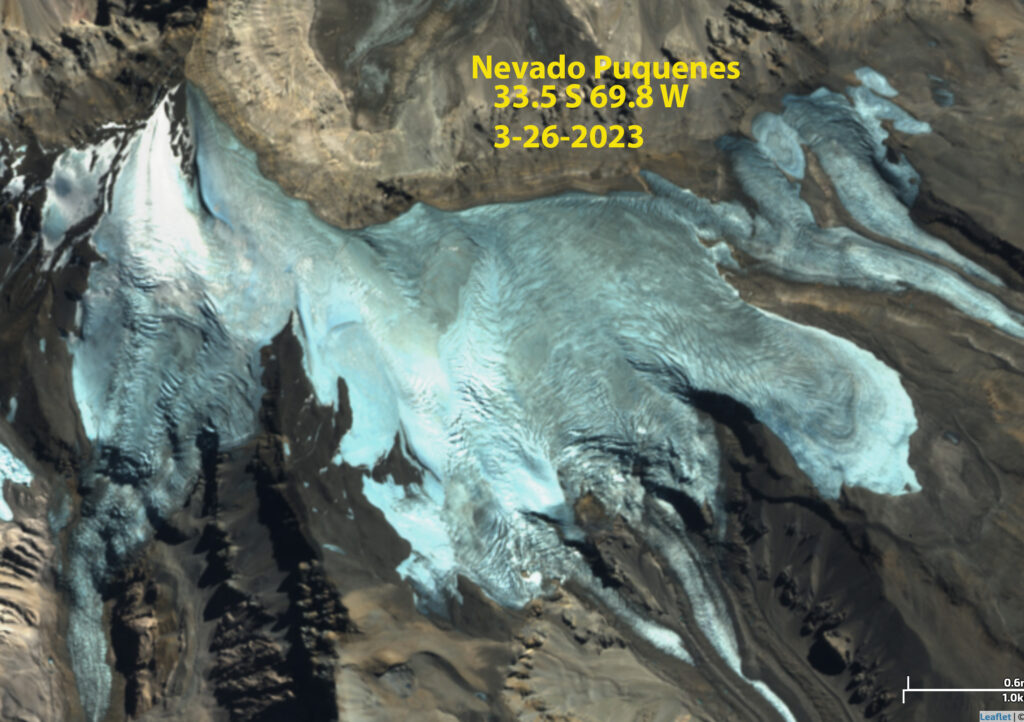

Nevado Piquenes, Argentina has less than 5% snowcover retained in this Sentinel image, right near the 6000+ m summit.

Bello and Yeso Glacier, Chile have no trace of snowcover for 2nd consecutive summer. The dirtier surface is leading to faster melt.

El Morado Glacier, Chile has no trace of snowcover for 2nd consecutive summer. The dirtier surface is leading to faster melt, and fragmenting.

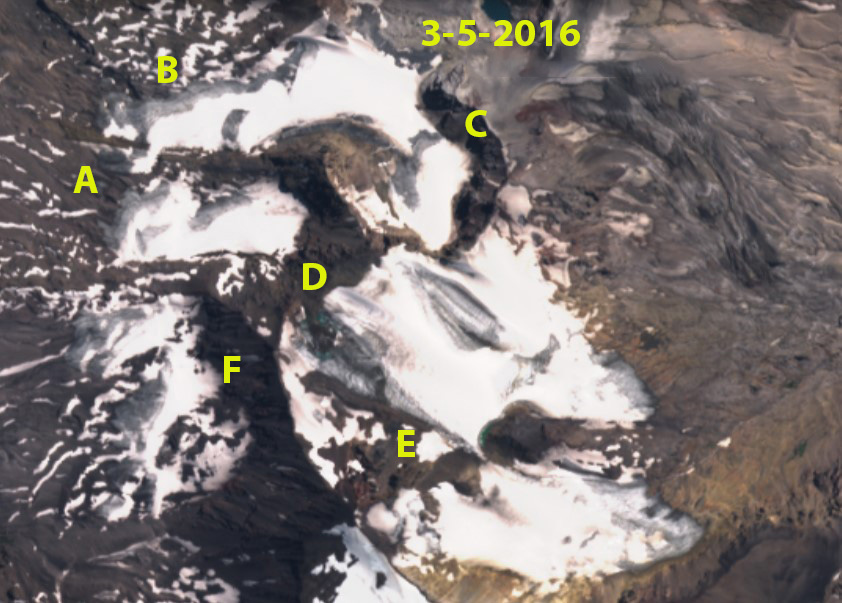

Volcan San Jose Glaciers in Sentinel image continues to fragment with a 2nd consecutive year without retained snowcove.

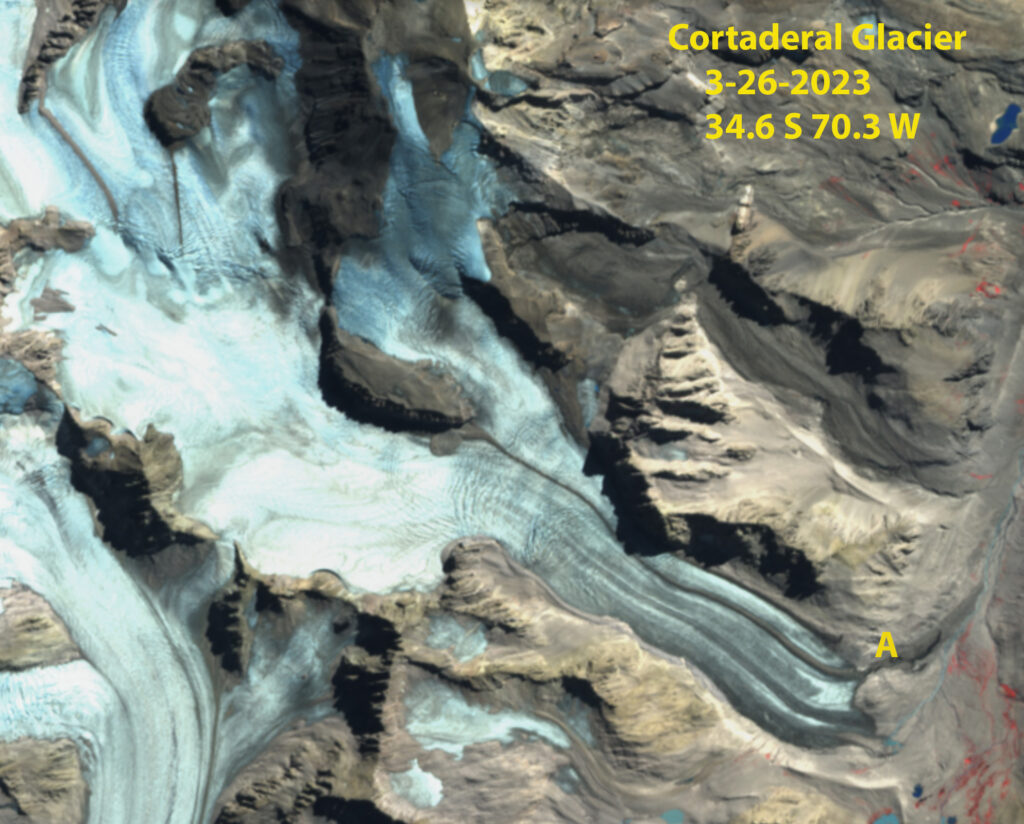

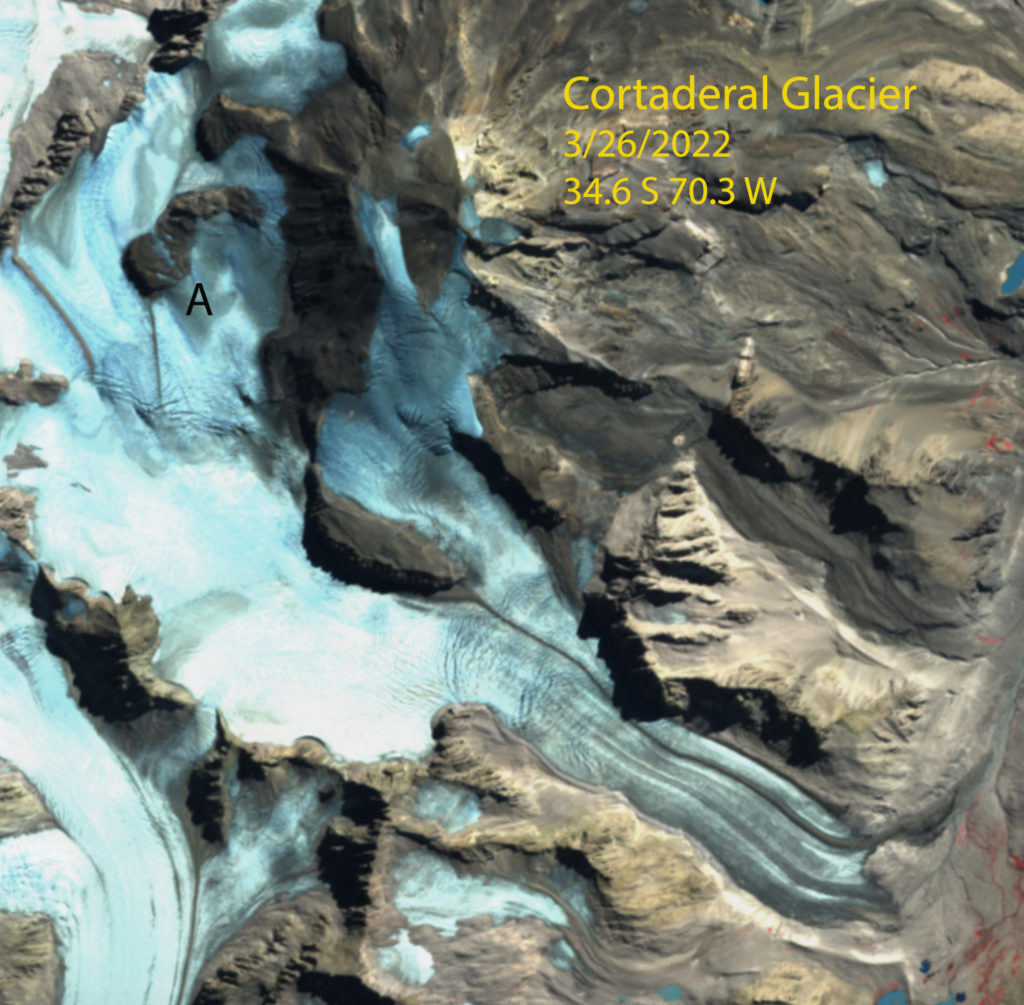

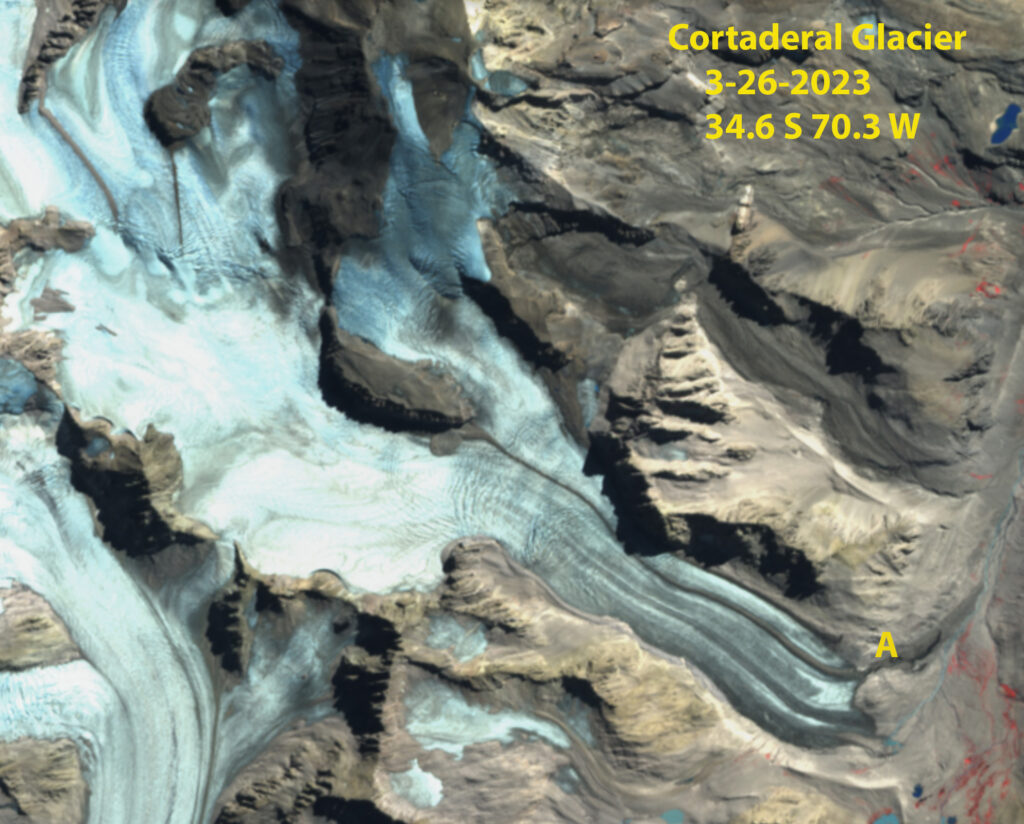

Cortaderal Glacier, Chile in Sentinel image with no retained snowcover this summer, leading to terminus tongue loss at Point A.

Corto, Fiero and Humo Glacier, Argentina with no retained snowcover in 2023, for 2nd consecutive summer. These glaciers feed the Rio Atuel, and their rapid retreat will lead to less summer glacier runoff.

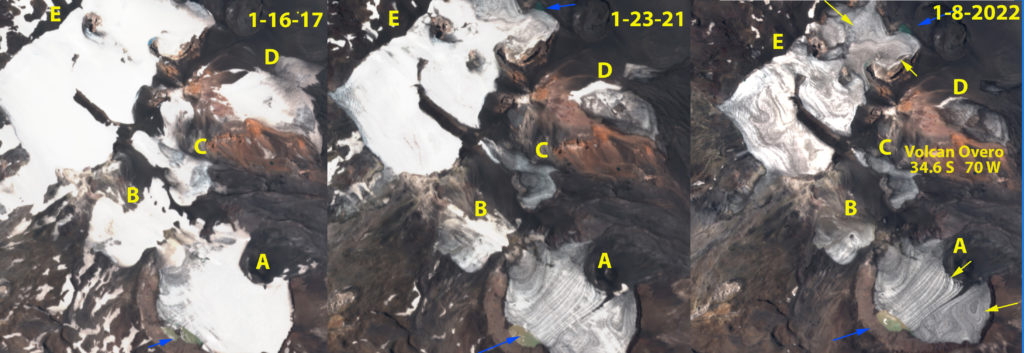

Volcan Overo in Sentinel image continues to fragment with no retained snowcover this summer, and bedrock expansion causing fragementation at Point A, B and C.

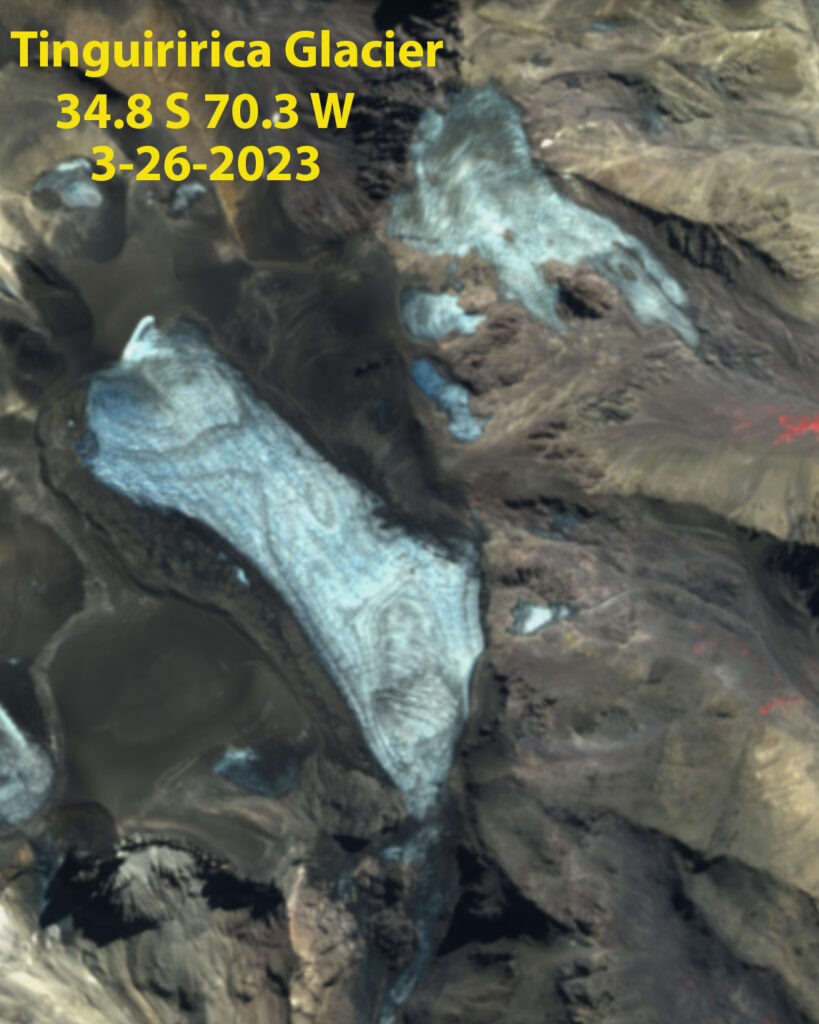

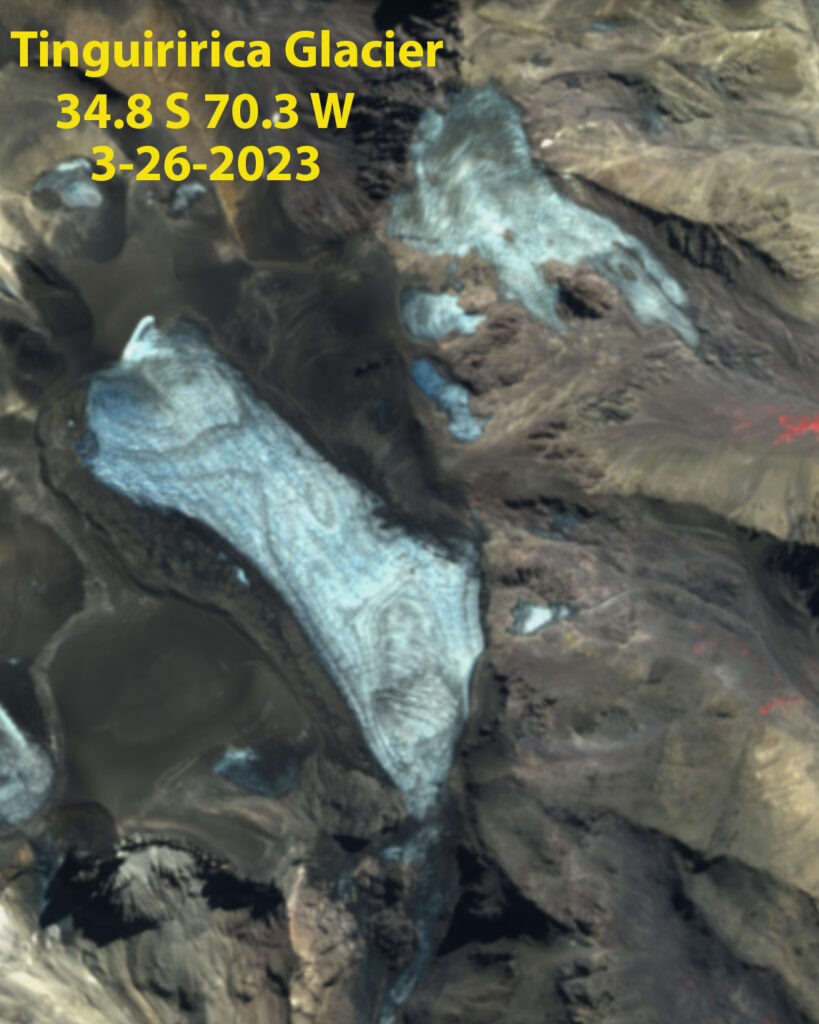

Tinguiririca Glacier, Chile drains into the river of the same name. In 2023 this fragmenting glacier lost all its snowcover for 2nd consecutive summer.

Cobre Glacier, Argentina lost all its snowcover in 2023, just like 2022. Here it has separated at Point B and nearly so at Point A.

Volcan Peteroa Glacier, Chile/Argentina border in Sentinel image continues to fragment at Point A with no retained snowcover, this is also leading to lake expansion at Point B.

Map of Central Andes indicating glacier locations from 33-36° S that we focus on here.