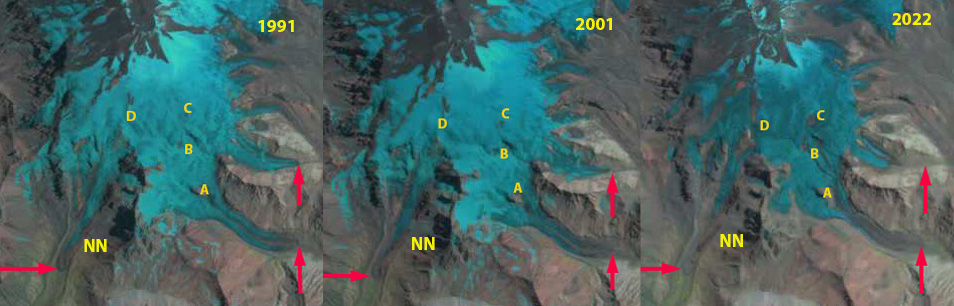

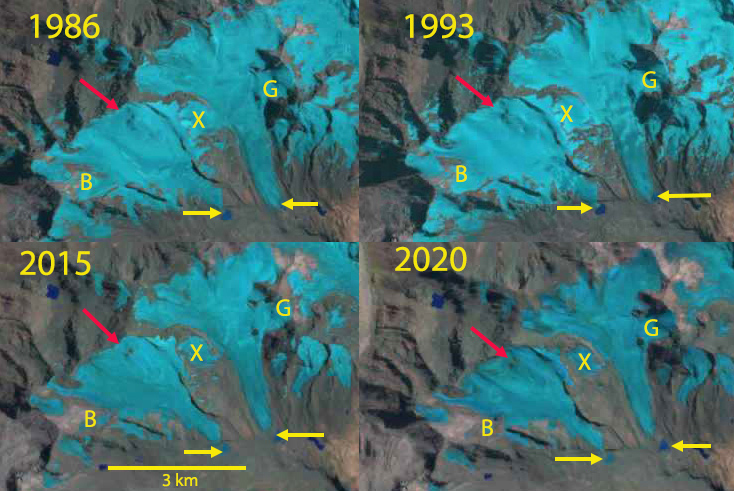

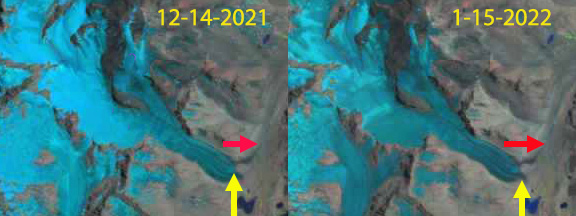

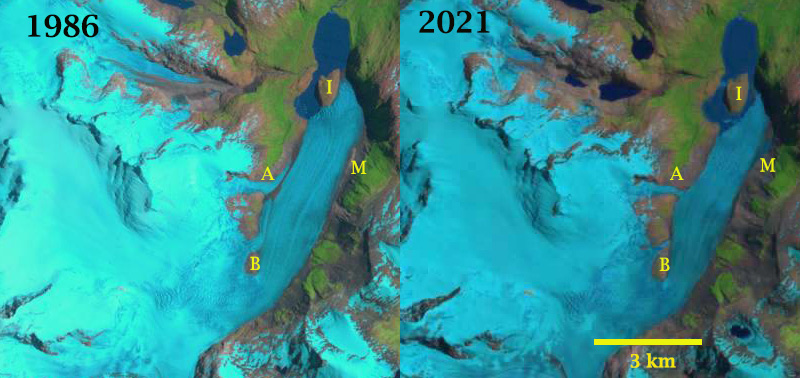

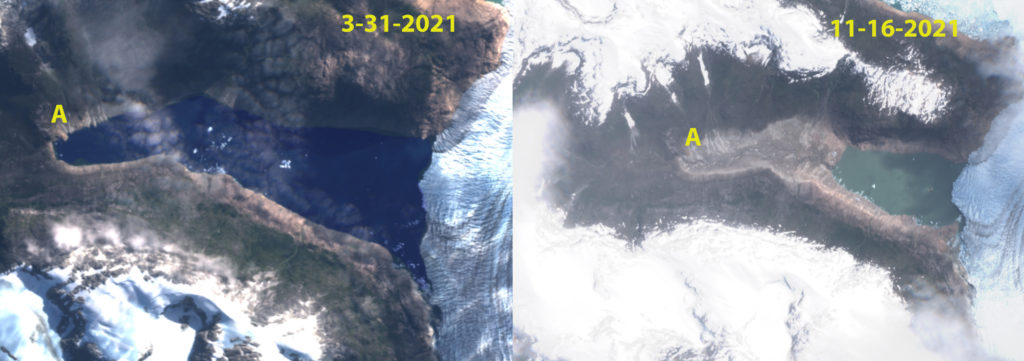

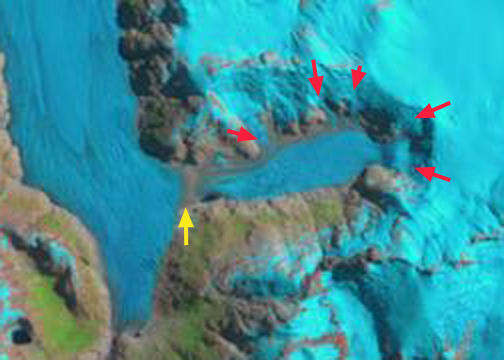

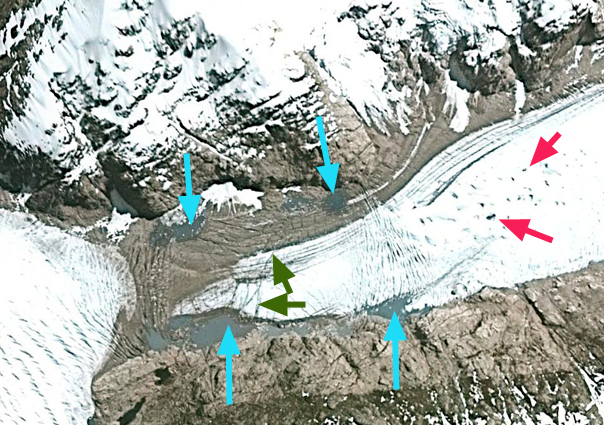

Landsat images of Sollipulli from 1986 and 2022. Point A-D are locations where the glacier spilled out of the caldera in 1986, but no longer does so in 2022.

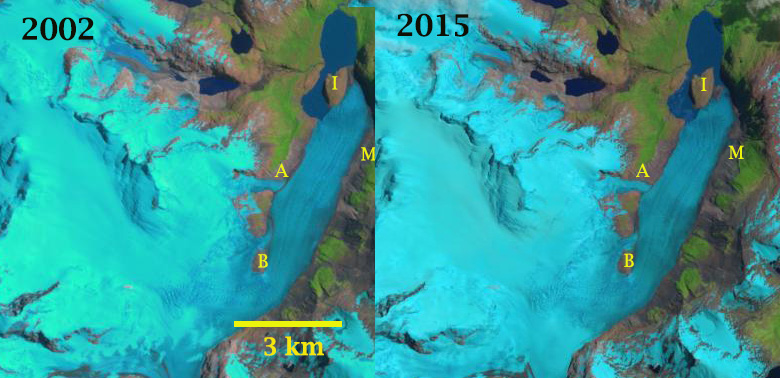

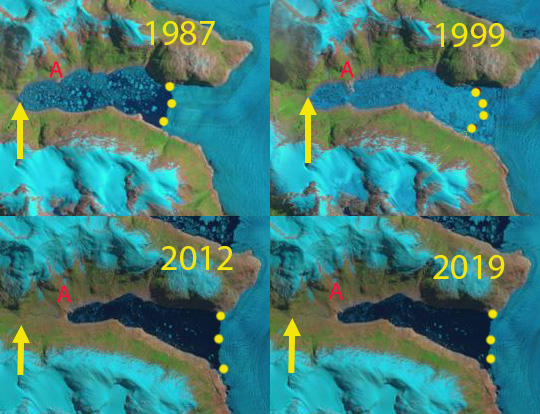

Nevados de Sollipulli is a volcano, is in the central Andes of Chile near the border with Argentina in Parque Nacional Villarica, Chile. The 4 km wide summit caldera at ~2100 m is filled by a glacier. The volcano is dormant last producing lava flows 700 years ago and last erupting 2900 years ago (NASA, 2017). Reinthaler et al (2019) identified a 27% decline in glacier area from 1986-2015 on 59 volcanoes in the Andes. The study included Sollipulli where the area declined from 16.2 km2 in 1986, 20 12.5 km2 in 1999 and 11.1 km2 in 2015 (Reinthaler et al 2019). Here we examine Landsat imagery illustrating the recession from 1986-2022 and the loss of all snowcover for most of the summer of 2022. The summer of 2022 led to early summer loss of most/all the snowpack on Central Andes glaciers from 30-40 S. (Pelto, 2022)

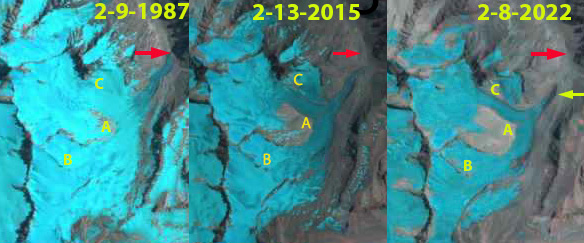

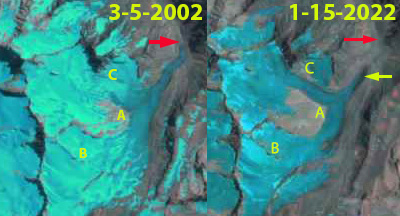

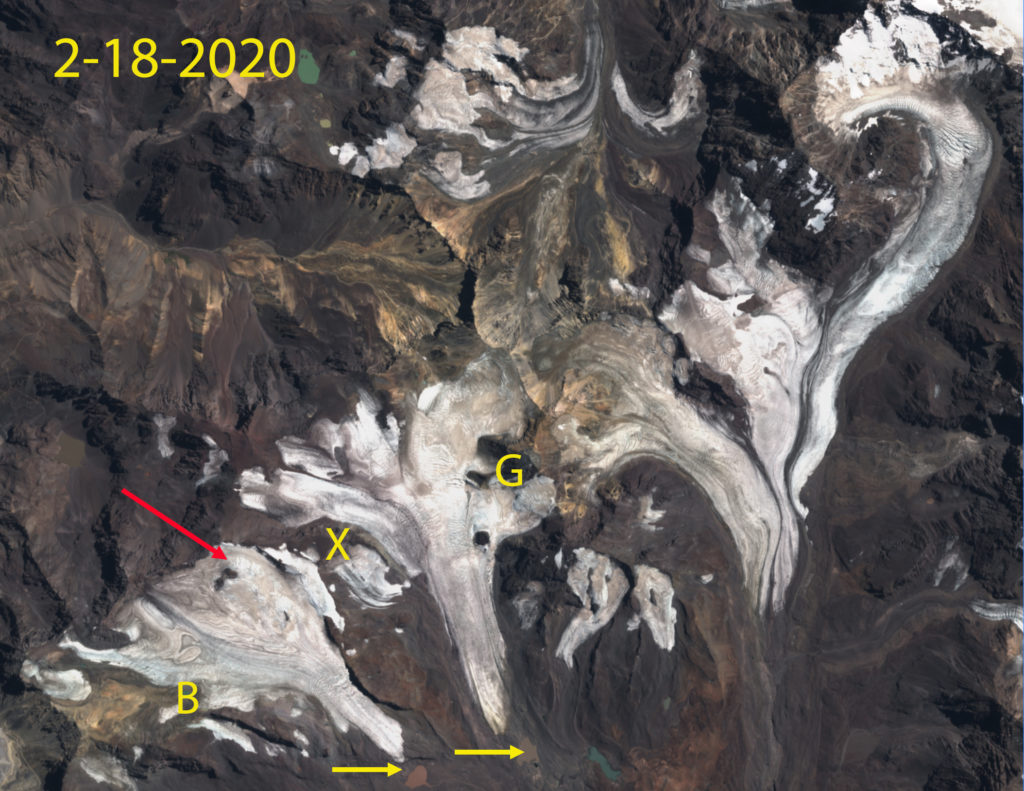

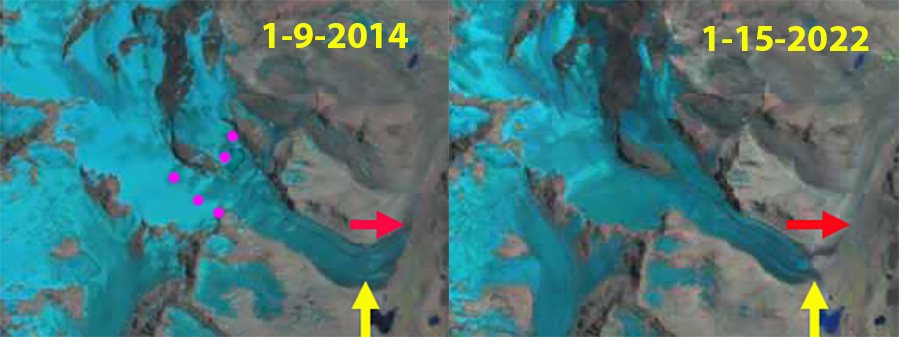

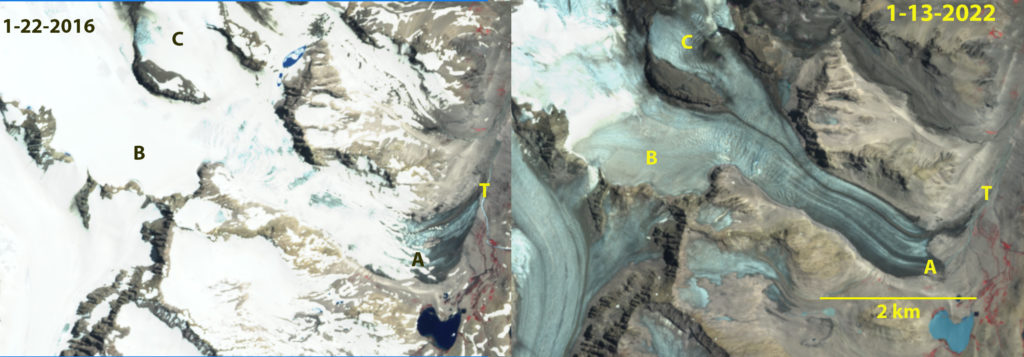

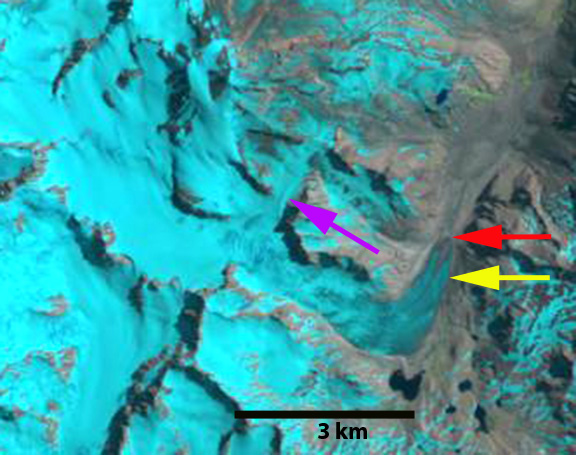

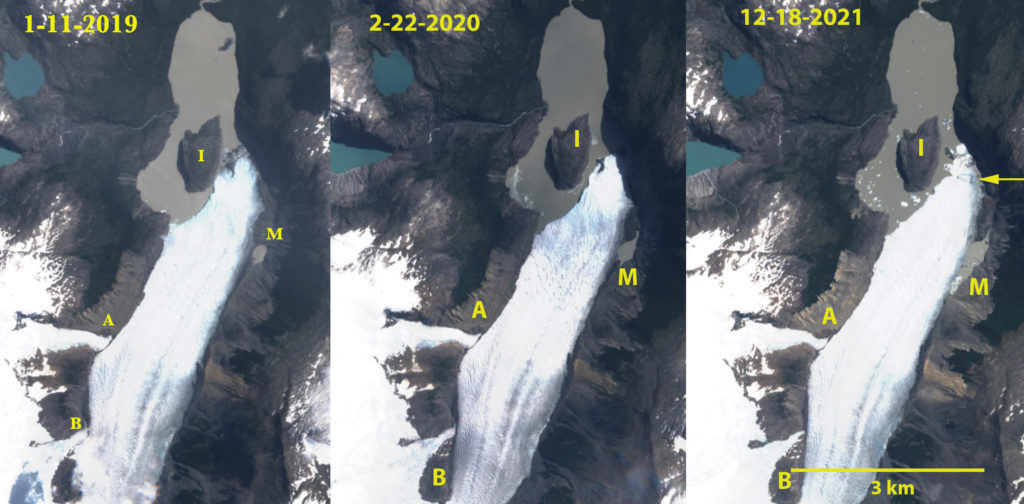

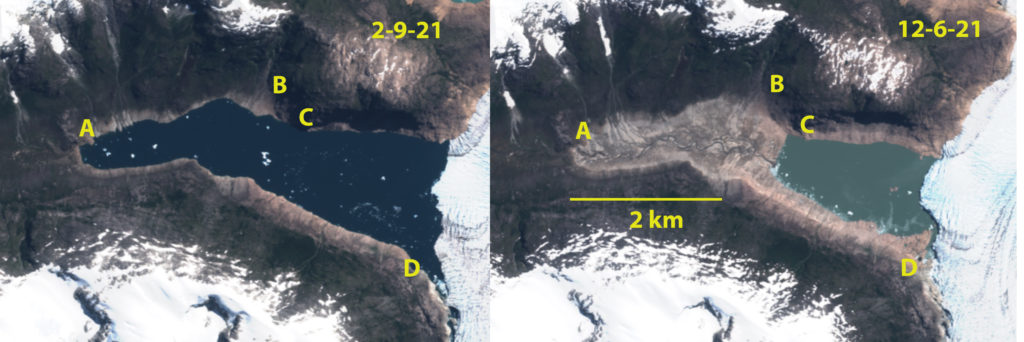

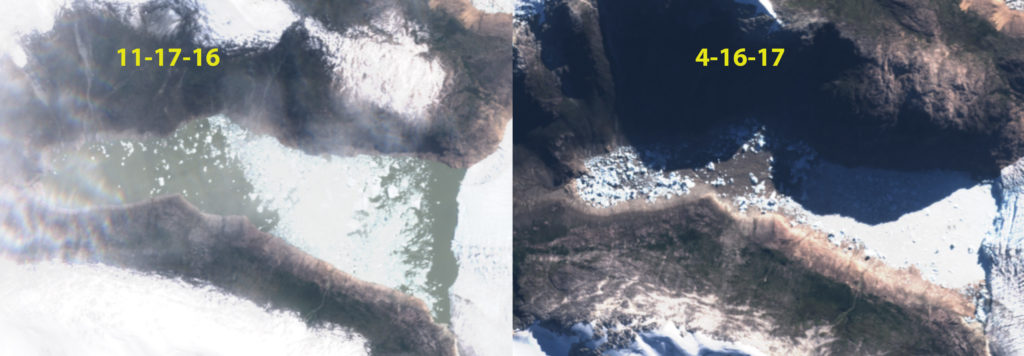

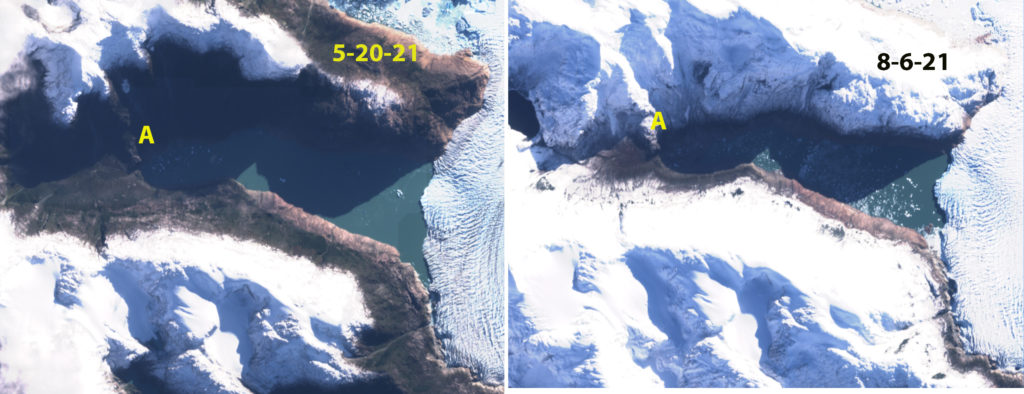

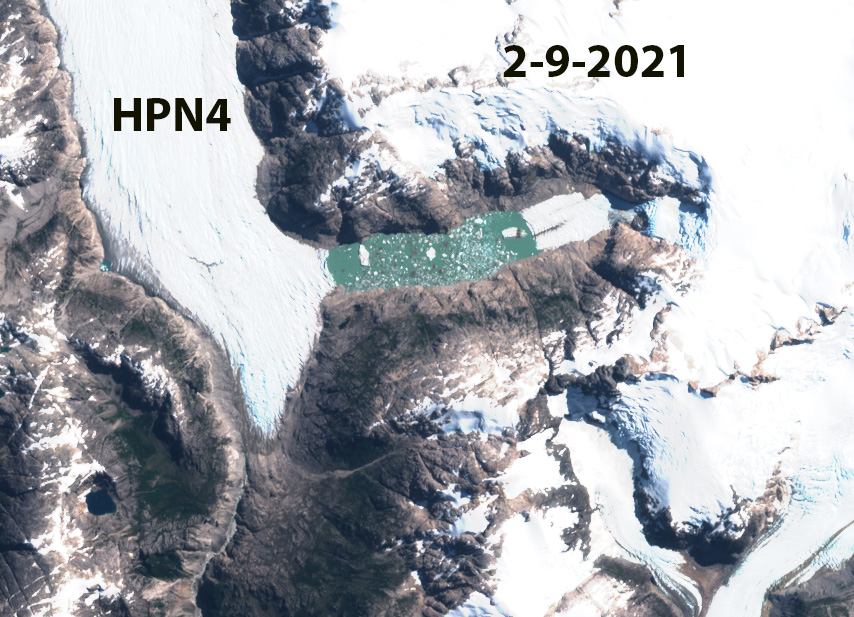

In 1986 a Landsat 5 image illustrates that the glacier not only fills but overflows the caldera at Points A-D, with Point A and B feeding significant glacier area. The glacier is also almost completely snowcovered in late February. In 2003 the glacier is still spilling over at Point A, and is almost entirely snowcovered in mid-February. On January 8, 2022 the glacier is already 95% free of snowcover with some snow patches on the NW margin. By January 24 the glacier is 99% snow free and remains snow free through mid-March in a Landsat and Sentinel image from 3-13 and 3-16 respectively. There is a small patch of relict glacier ice near Point B, while the former glacier at Point A has disappeared. The annual layering preserved in the glacier ice as seen in the Landsat Band 5 image will continue to evolve as the glacier thins. The dirty nature of this ice enhances solar radiation melting, particularly compared to snowcover. Two months of exposure at the 2100 m elevation ice cap will have led to several meters of ice loss. The extent of the glacier has declined to 10.2 km2 in March 2022 a 37% decline since 1986.

Landsat images indicating the near complete snowcover in Landsat 7 image from 2003 and the loss of all snowcover that continued from January until at least March 13 2022. Note the annual layers preserved in the glacier ice now exposed at the surface.

Sollipulli Glacier in early January with only a fringing area of snowpack along the northwest margin. Sixty-four days later the glacier is still bare of snowpack.