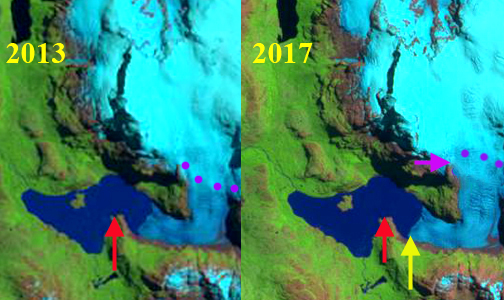

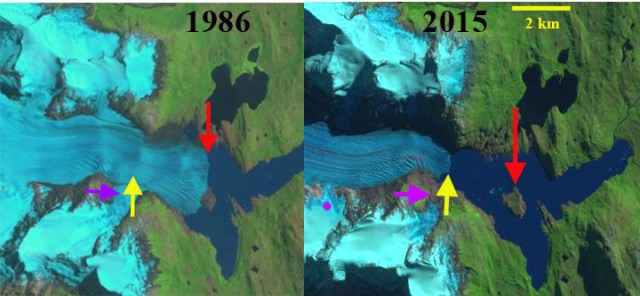

Benito Glacier comparison in 1987 and 2015 indicating the terminus position in 1987 red arrows, yellow arrows the 2015 terminus positions, purple arrows where glacier thinning is expanding bedrock areas, the snowline is indicated by purple dots.

Glacier Benito is a temperate outlet glacier on the west side of the North Patagonian Icefield the glacier is south of Fraenkel Glacier and north of Acodado Glacier. Loriaux and Casassa (2013) examined the expansion of lakes of the Northern Patagonia Ice Cap. From 1945 to 2011 lake area expanded 65%, 66 square kilometers. Willis et al (2012) noted a 2.0 m ice thickness loss per year from 2001-2011 in the ablation zone. Mouginot and Rignot (2015) indicate that the velocity of Benito Glacier is between 200-500 m per year along the center line below the snowline. Glasser et al (2016) note that this glacier has limited debris cover. In the last two years an expedition organized by Martin Sessions has been examining Benito Glacier and has been reporting from the field this month.

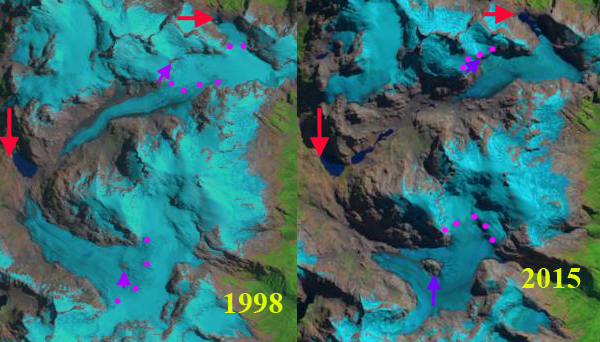

Benito Glacier in 1987 terminated on an outwash plain. The glacier has five key distributary termini two of which have open proglacial lakes. By 2015 there are six tributary termini, five ending in lakes, with one having retreated out of a lake basin. The two tributaries to the north indicated with arrows each retreat approximately 1 km from 1987 to 2015 and in both cases are no longer calving termini. The main glacier terminus has retreated into a proglacial lake, with a retreat of 2 km from 1987 to 2015. The lowest 1.5 km has a low slope and peripheral lakes suggesting the terminus lake will expand substantially as Benito Glacier retreat continues. The transient snowline in the two images 2015 and 2016 is at 900 m. Glasser et al (2016) note that this glacier average transient snowline in 2013-2016 is at 1000 m. Winchester et al. (2013) identified thinning of 150 m in the lower ablation zone from 1973-2011, with the most rapid thinning from 2007-2011.

Benito Glacier comparison in 1987 and 2015 indicating the terminus position in 1987 red arrow, yellow arrow the 2015 terminus positions, and the snowline is indicated by purple dots.

Google Earth image in 2012 of Benito Glacier indicating proglacial lake areas at the green arrows.