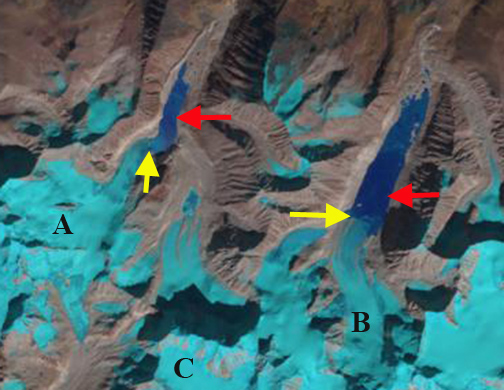

Comparison of Brady Glacier in 1986 and 2016 Landsat images. The snowline is similar in May 2016 and August 1986. Lakes noted are: A=Abyss, B=Bearhole, D=Dixon, N=North Deception, O=Oscar, Sd=South Dixon, Sp=Spur, T=Trick.

Brady Glacier, is a large Alaskan tidewater glacier, in the Glacier Bay region that is beginning a period of substantial retreat Pelto et al (2013). In 2016 the melt season has been intense for the Brady Glacier in Alaska. Pelto et al (2013) noted that the end of season observed transient snowline averaged 725 m from 2003-2011, well above the 600 m that represents the equilibrium snowline elevation. On May 20, 2016 the transient snowline (TSL) is at 500 m. Typically the TSL reaches 500 m in early July: 7/13/2004=530; 7/8/2005=550, 7/3/2006=500, 7/22/2007=520, 7/3/2009=500; 7/10/2013=500. The high early season snowline is indicative of an early opening and filling of the many proglacial lakes that secondary termini of the glacier end in. The lakes Trick, North Deception, Dixon, Bearhole, Spur, Oscar, and Abyss continue to evolve. In addition two new lakes have developed. The changes are evident in a comparsion of 1986 and 2016 Landsat images. The TSL on May 20/2016 is remarkably similar to the August 20, 1986 TSL.

2010 Landsat image of the glacier indicating the 1948 margin in Orange and the 2016 margin in yellow. Lakes noted are: A=Abyss, B=Bearhole, D=Dixon, N=North Deception, O=Oscar, S=Spur, T=Trick.

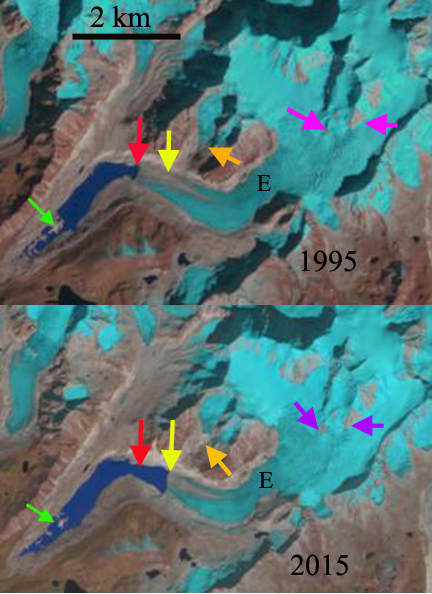

There is a consistent pattern in the change in position of the glacier margin at each of the lakes between 1948 and 2010. The rate of retreat of the glacier margin at all seven lakes accelerated later during this period; the mean retreat rate is 13 m/a from 1948 to 2004 and 42 m/a from 2004 to 2010 (Pelto et al, 2013). Lake area and calving fronts were measured for each lake: Spur, Abyss, North Deception, Bearhole, Oscar, and East Trick based on the September 2010 imagery, with earlier measurements from Capps et al. (2010). Lake areas have increased as a result of glacier retreat, and can decrease due to declines in surface water levels as previously ice-dammed conduits form to drain the lake. Lake water levels have fallen in Abyss, Bearhole, Dixon, North Deception, Spur, and Trick since 1948 Capps et al (2010). Only Oscar Lake, the most recent to form, has maintained its surface level. Retreat of the glacier margin has been greatest at Bearhole, North Deception Lake, and Oscar Lake, which as a consequence have expanded substantially in area. Lake water level declines at Abyss, Spur, and Trick have offset the increase in area resulting from glacier retreat, leading to small changes in lake area. The seven lakes have changed dramatically in response to this acceleration in retreat.

Trick Lakes: In 1986 North and South Trick Lake are proglacial lakes in contact with the glacier. By 2016 the two lakes are no longer in contact with the glacier, water levels have fallen and a third lake East Trick Lake has formed. The more recently developed East Trick Lake is the current proglacial Trick Lake, a large glacier river exits this lake and parallels the glacier to the main Brady Glacier terminus, going beneath the glacier for only several hundred meters.

2014 Google Earth image of Trick Lakes, and the glacier river exiting to the main terminus, purple arrows.

North Deception Lake had a limited area in 1986 with no location more than 500 m long. By 2016 retreat has expanded the lake to a length over 2 km. The width of the glacier margin at North Deception Lake will not change in the short term, but the valley widens 2 km back from the current calving front, thus the lake may grow considerably in the future.

South Dixon Lake This new lake does not have an official name. It did not exist in 1986, 2004, 2007 or 2010. It is nearly circular today and 400 m in diameter.

Dixon Lake: It is likely that retreat toward the main valley of the Brady Glacier will lead to increased water depths at Dixon Lake, observations of depth of this lake do not exist. Retreat from 1986 to 2016 has been 600 m.

Bearhole LakeBearhole Lake is expanding up valley with glacier retreat, and there are no significant changes in the width of the valley that would suggest a significant increase in calving width could occur in the near future. Currently the lake is 75 m deep at the calving front and there has been a 1400 m retreat since 1986 Capps et. al. (2013).

Spur Lake:It is likely that retreat toward the main valley of the Brady Glacier will lead to increased water depths at Spur Lake. the depth has fallen as the surface level fell from 1986-2016 as the margin retreated 600 m, leaving a trimline evident in the 2016 imagery.

Oscar Lake has experienced rapid growth with the collapse of the terminus tongue. Depth measurements indicate much of the calving front which has increased by an order of magnitude since 1986 is over 100 m. The tongue as seen in 2014 Google Earth image will continue to collapse and water depth should increase as well. The central narrow tongue has retreated less than 200 m since 1986, but the majority of the glacier front has retreated more than 1 km since 1986.

Google Earth image of Oscar Lake, illustrating the number of large icebergs of this ongoing terminus collapse.

Abyss Lake: Continued retreat will lead to calving width expansion> The retreat from 1986 to 2016 has been 400 m. The water depth has been above 150 m at the calving front for sometime and should remain high.

Glacier thinning and retreat near the lakes dammed by Brady Glacier have led to changes in the widths of calving fronts between. The combined increase in the width of the six secondary calving fronts is 34% from 1948 to 2004, and 15% from 2004 to 2010 (Pelto et al, 2013) With the inclusion of South Dixon Lake and continued expansion of Dixon and Oscar Lake the calving width has continued to increase up to 2016. Calving widths at Bearhole Lake, Spur Lake, and Trick Lake will not change appreciably. Spur Lake and Trick Lake parallel the margin of the glacier, and although this margin will likely continue to recede, the length of the depression filled by the two lakes probably will not change.

Water depth is an important factor affecting the calving rate of glaciers in lacustrine environments; velocity and calving rate increase with water depth by a factor of 3.6 (Skvarca et al., 2002). Capps et. al. (2013) determined the bathymetry and calving depths of five of the lakes at Brady Glacier. Water depths increase toward the calving fronts at Abyss Lake, Bearhole Lake, Oscar Lake, and Trick Lake; only at North Deception Lake does the water not currently become deeper towards the calving front; however it almost certainly will as the east margin moves into the main Brady Glacier valley. The observations suggest that mean calving depths of proglacial lakes, at least in the short term, will increase with continued retreat. Increases in calving width and depth will lead to increased calving at the secondary termini in the near future (Pelto et al, 2013).