The Selwyn Mountains, Yukon Territory are host to numerous small alpine glaciers that have been rapidly losing area and volume. David Atkinson, atmospheric scientist at University of Victoria has been examining the weather conditions leading to the extensive melting and higher snowlines. From 1958-2007 glaciers lost 22% of their volume in the Yukon (Barrand and Sharp, 2010). Due to the high snowlines Atkinson notes the rate of retreat has increased since then. The freezing level as determined by the North American Freezing Level Tracker illustrates this point with 2015 being the highest winter freezing level. Here we examine response of the Rogue River Icefield using Landsat imagery from 1986-2015. The icefield is at the headwaters of the Rogue River and also drains into the Hess River.

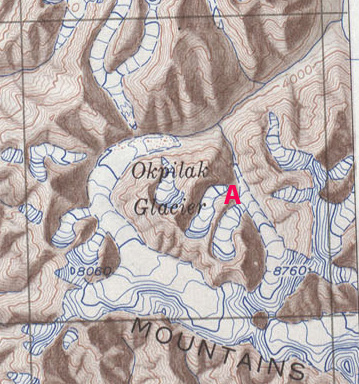

Canada Toporama map of the region.

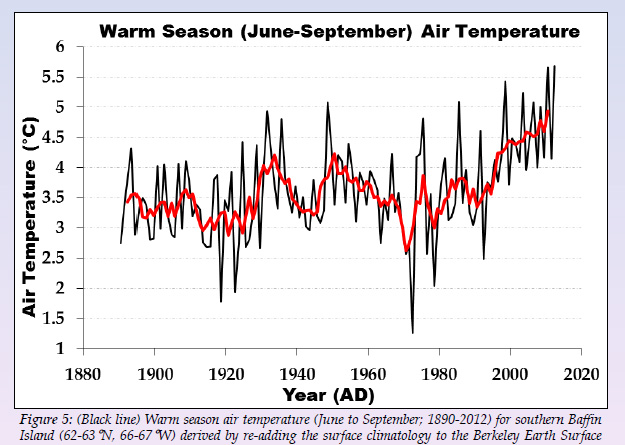

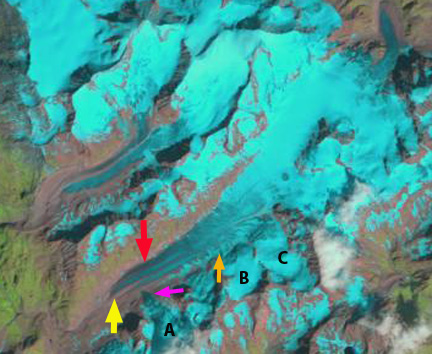

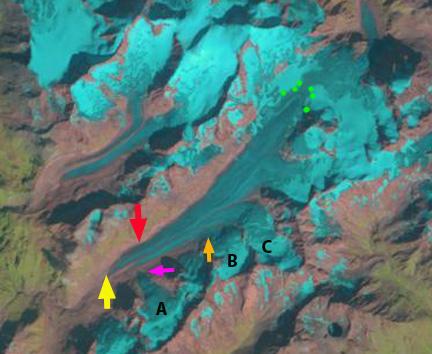

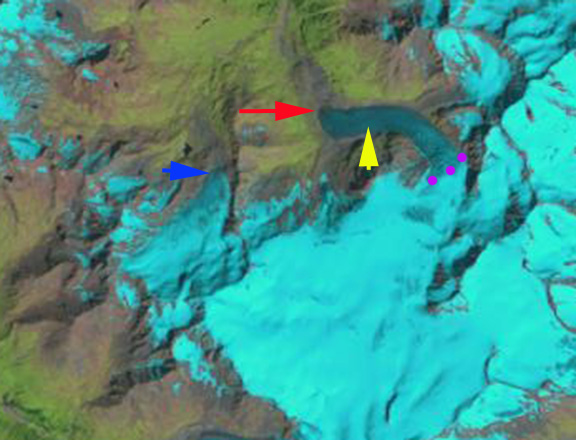

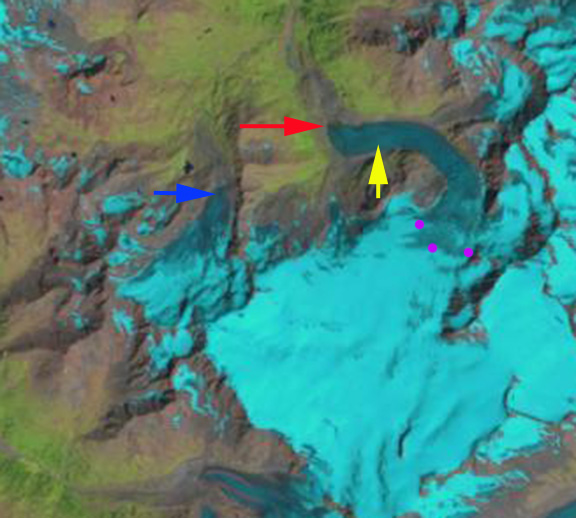

Selwyn Mountain November-April freezing levels.

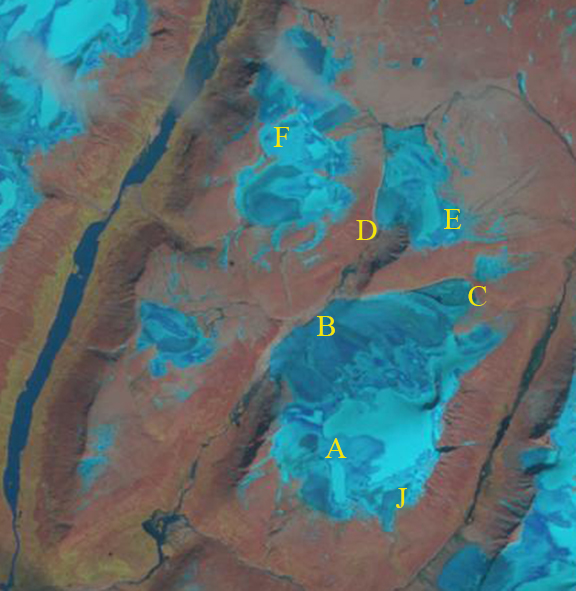

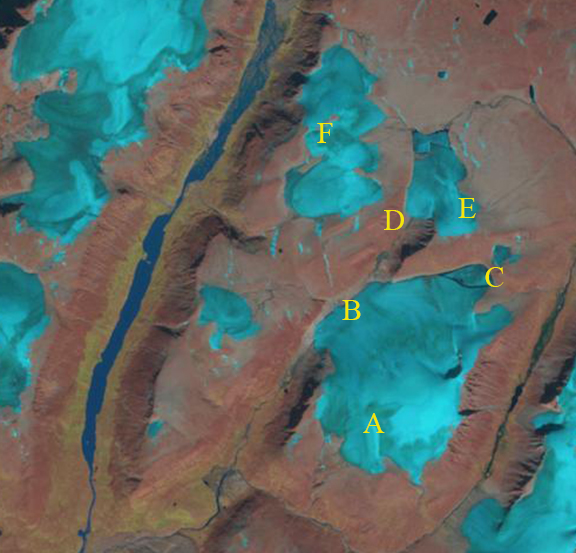

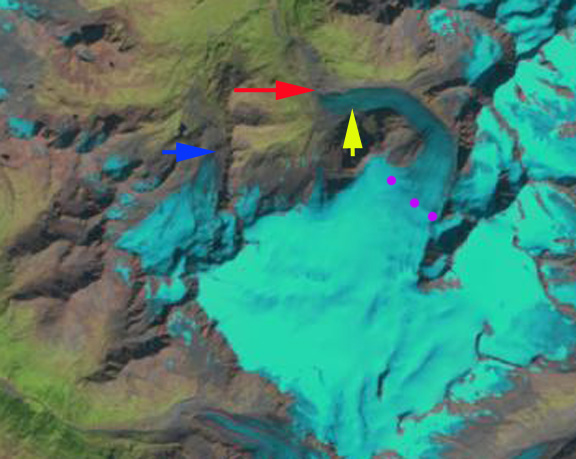

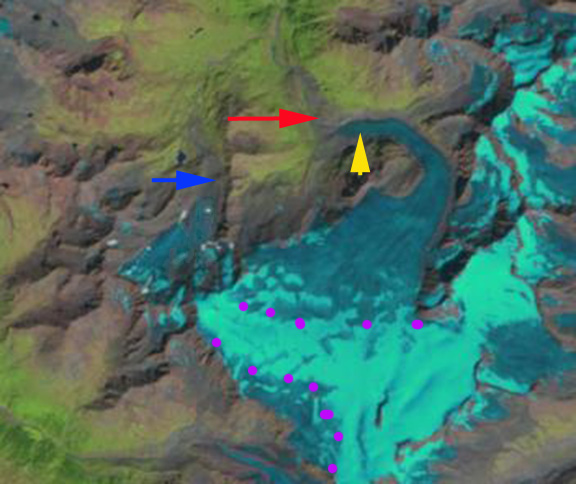

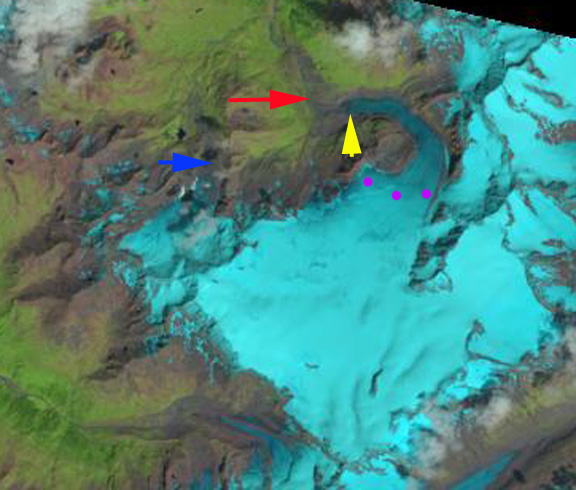

In 1986 the primary icefield glacier is shown with blue arrows above indicating flow direction towards both the north and southeast terminus. The north terminus reached the valley bottom at the red arrow and the southeast terminus extended to the yellow arrow in 1986. All arrows are in fixed locations in every image. The purple and orange arrows indicate the terminus of smaller valley glaciers in 1986. The pink arrow indicates a valley glacier that is split into two terminus lobes by a ridge. By 1992 the only significant change is the southeast terminus of the primary glacier at the yellow arrow. In 2013 the snowline is exceptionally high at 2200 meters, with glacier elevations only reaching 2300 m. Retreat is extensive at each terminus. In 2015 the satellite image is from early July and the snowline has not yet risen significantly. Terminus retreat at the yellow arrow is 900 meters, at the red arrow 400 m, at the purple arrow 600 m, at the pink arrow 400 m and at the orange arrow 500 m. Given the length of these glaciers at 1-3 km this is a substantial loss of every glacier. Further south in the Yukon high snowlines are also a problem for Snowshoe Peak Glacier.

1986 Landsat image

1992 Landsat image

2013 Landsat Image

2015 Landsat image