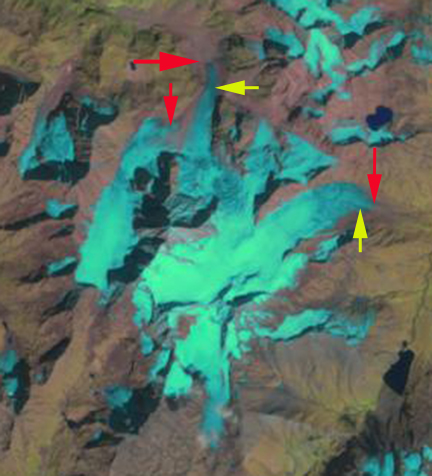

Belopolskijbreen comparison in 1990 and 2014 Landsat images. Red arrow is the 1990 terminus location, yellow the 2014 extent of the a bedrock ridge separating the two lobes of the glacier, and purple arrow an area of thinning at the head of the glacier.

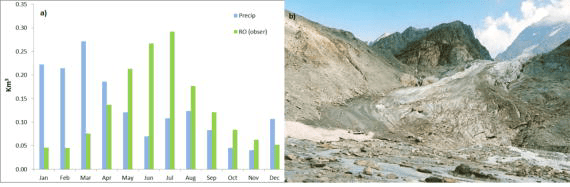

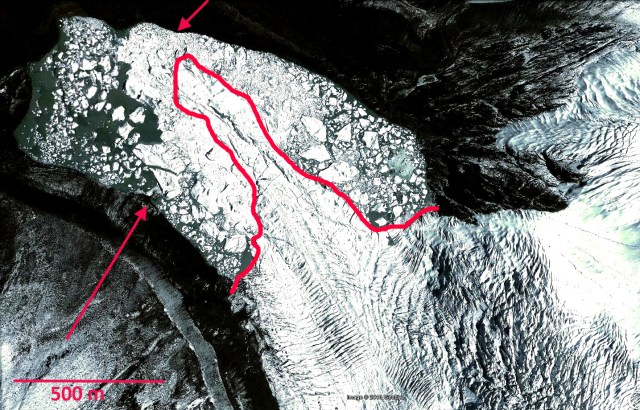

Most of the attention on Svalbard glaciers goes to the larger tidewater glaciers, which collectively having been losing volume rapidly. Belopolskijbreen in Sorkappland near the southern tip of Svalbard a land based glacier that we examine here using Landsat images from 1990 to 2014. The glacier is adjacent to Olsokbreen a rapidly retreating tidewater glacier. In 1990 and in the TopoSvalbard maps indicate the glacier terminating in proglacial lakes A and B. The snowline is restricted to the very top of the glacier. With limited retained snowpack anywhere, the glacier will thin and retreat significantly. In the middle of the glacier near the red arrow is a bedrock ridge that 700 m into the glacier. By 2014 the bedrock ridge has extended to the yellow arrow, an additional 700 m. The glacier has retreated 500 m from Lake A and 650 m from Lake B. The retreat of approximately 500 m across a 4 km wide glacier front plus the expansion of bedrock in the middle, represents more than 2 square kilometers of area lost. This retreat will continues as the snowline has been limited to the very top of the glacier in 2013, 2014 and 2015. The 2013 Landsat image below indicates the snowline with purple dots. The snowline is above 375 m with the top of the glacier at just over 400 m. The glacier has 10% snowcover retained at a maximum, the minimum needed for equilibrium is 50%.

Nuth et al (2013) determined that the glacier area over the entire archipelago has decreased by an average of 80 km2 per year over the past 30 years, a 7% reduction. In the most recent period 1990-2007, terminus retreat was larger than in an earlier period from 1930-1990, while area shrinkage was smaller. Svalbard is host to 163 tidewater glaciers with a collective calving front of 860 km (Błaszczyk et al, 2009). Blaszczyk et al. (2013) reported the total area of the glacier cover lost in Hornsund Fjord area from 1899–2010 was approximately 172 square kilometers, which is just north of Sorkappland.

TopoSvalbard map of Belopolskijbreen, terminating at Lake A and B. Red arrow marks ridge separating glacier terminus into two lobes.

2013 Landsat images. Note the snowpack limited to the very top of the glacier, purple dots