This is an index of posts on the response of specific Greenland glaciers to climate change. In the 1980’s when I first worked on Jakobshavn Isbrae, Greenland there was not much research occurring on the glaciers. Today in response to the dynamic changes discussed below and glacier by glacier in the index links, Greenland is the focus of numerous extensive, ongoing and important research projects. In 2015 scientists are gearing up for the main field season to better identify and understand the current and future response of this critical ice sheet. At the time of each post I reference the specific research relevant, the posts are from 2009-2014. In the intervening period new research has made some further advances, and I will endeavor to update each post to reflect this. The posts illustrate the significant response of Greenland Glaciers to climate change regardless of what type of glacier they are. The Polar Portal has developed an online viewer of change on selected glaciers. Each year the Arctic Report Card updates annual observations of Greenland Ice Sheet Change. The posts have benefitted from the insights and observations of Espen Olsen. Any questions about a glacier or suggestions on a glacier to look at let me know.

Greenland

Humboldt Glacier

Petermann Glacier

Kuussuup Sermia

Thrym Glacier Retreat

Tiningnilik Glacier Lake

Jakobshavn Isbrae

Zachariae Isstrom

Umiamako Glacier

Umiamako Glacier

Alison Gletscher

Dodge and Storm Glacier

Kong Oscar Glacier

De Reste Bugt

Qaleraliq Glacier

Upernavik Glacier

Apuserajik Glacier

Epiq Sermia

Sarqardliup Seremia

Narssap Sermia

Steensby Glacier

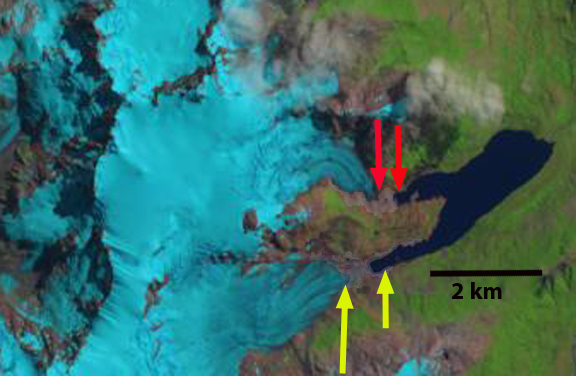

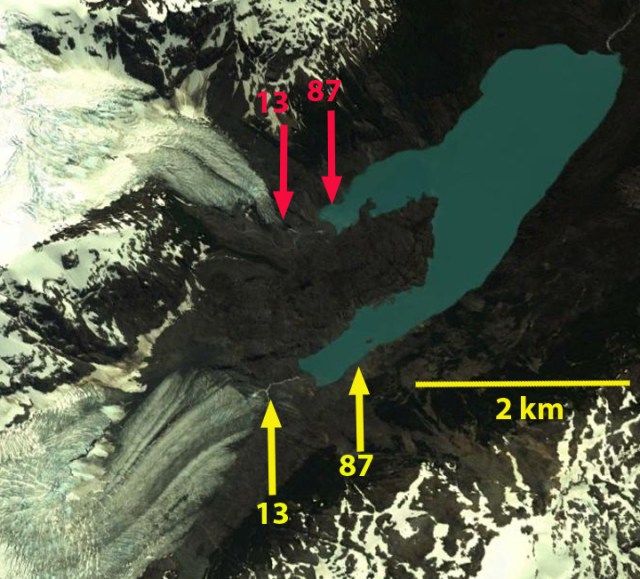

Sortebrae Glacier, Greenland

Tracey Gletscher

Nioghalvfjerdsbrae-79 Glacier

Steenstrup Glacier

Rinks Gletscher

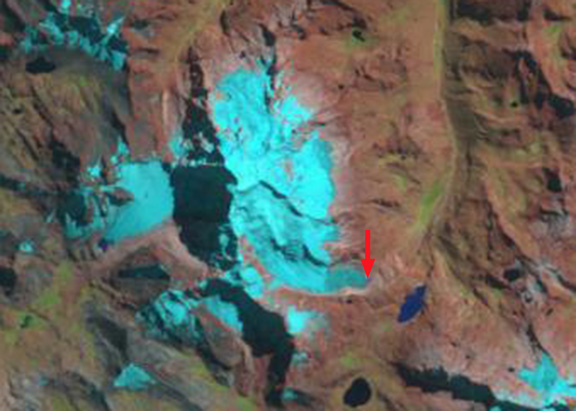

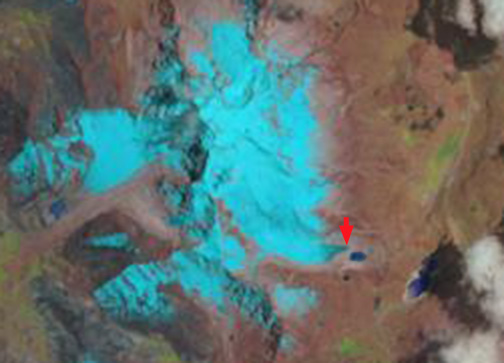

Puisortoq

Mittivakkat Glacier

Ryder Glacier

Kangiata Sermia

Koge Bugt

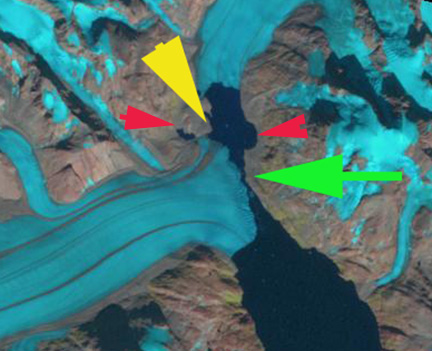

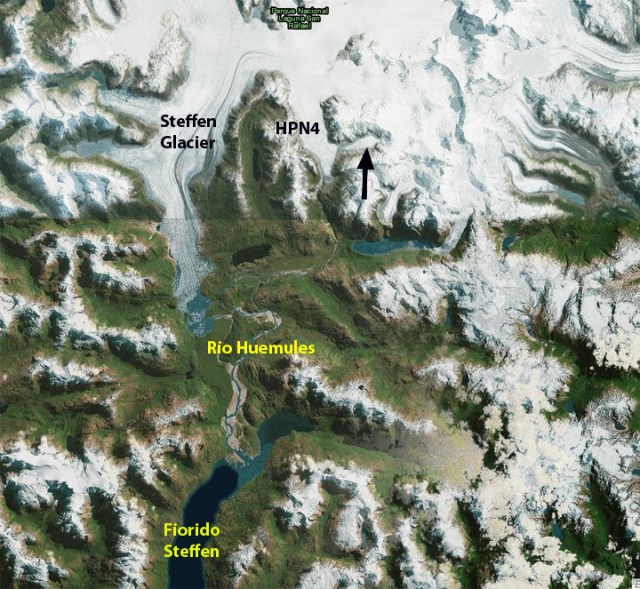

Base Map above right indicates the glacier types 1-4 distribution and key glacier locations with specific posts below. P=Petermann, R=Ryder, S=Steensby, H=Humboldt, Z=Zacharaiae, D=De Reste Bugt, T=Thyrm, N=Narssap Sermia, J=Jakobsan, E=Epiq Sermia, U=Umiamako, K=Kong Oscar.

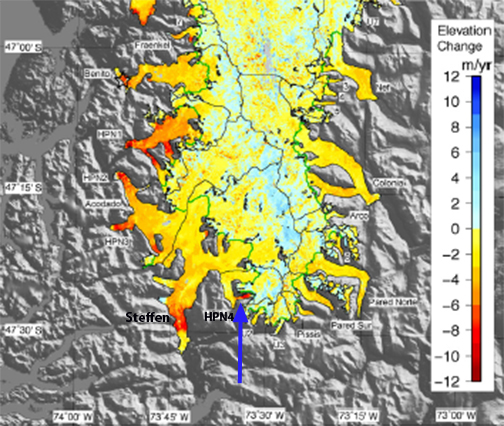

Variations in Greenland Ice Sheet outlet glacier behavior

The Greenland Ice Sheet has an area of 2.17 million square kilometers (1.28 million square miles) and spans 18 degrees of latitude from north to south. It is not surprising that over this vast area that the geology and climate vary substantially and that this leads to variations in behavior of Greenland glaciers. Our tendency is to lump the Greenland Ice Sheet into one category impacted similarly by each of the dynamic forces that impact flow. This is akin to saying banks, credit unions and savings and loan institutions are impacted similarly by all the economic forces. In the case of a recession there is a shared signal, just as with global warming there is a shared signal among Greenland glaciers. This is a simplification that does not work. In this article we divide the glaciers into four main categories to illustrate the different properties and sensitiveness of each. This is an updated version of an article Dan Bailey and I wrote first for Skeptical Science, updated here with links above to the individual glaciers that emphasize the specific changes and with new references. In recent years the most striking aspect of Greenland Glaciers is that the signal of change is so strong and on so many of the different glaciers. The specific response is different, which if we try to lump the glaciers into one category, makes the data look noisy. Instead if we look at the response of glaciers with similar dynamics than the signal of response is strong indeed. Csatho et al (2014) note the variation in ice thickness across the ice sheet for the 1993-2012 period and that 48% of the thinning is driven by ice dynamics. The net loss is an equivalent contribution of 0.67 mm/year to sea level rise.

Greenland glaciers fall into at least 4 common types, each with its own unique sensitivity to sea surface temperature, surface melting, meltwater lubrication, calving changes, etc.

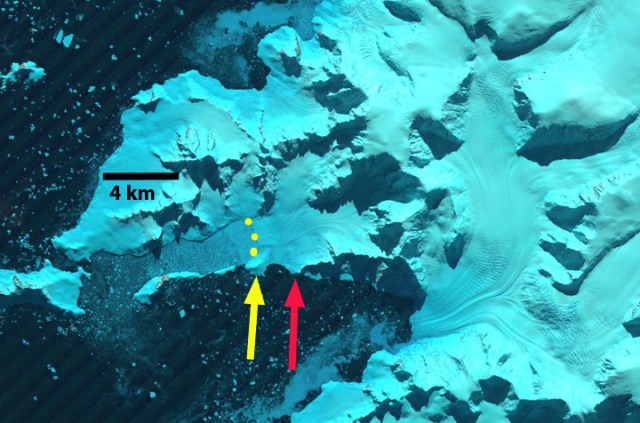

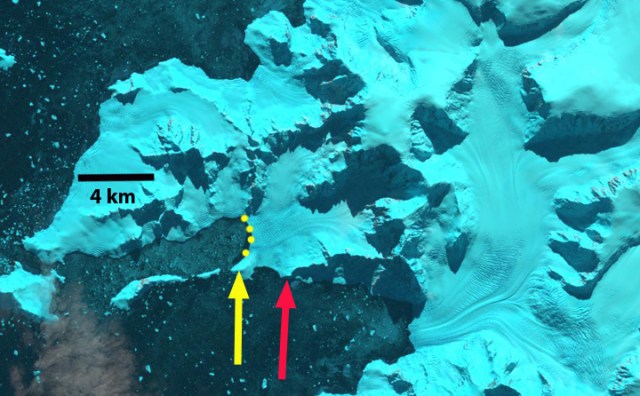

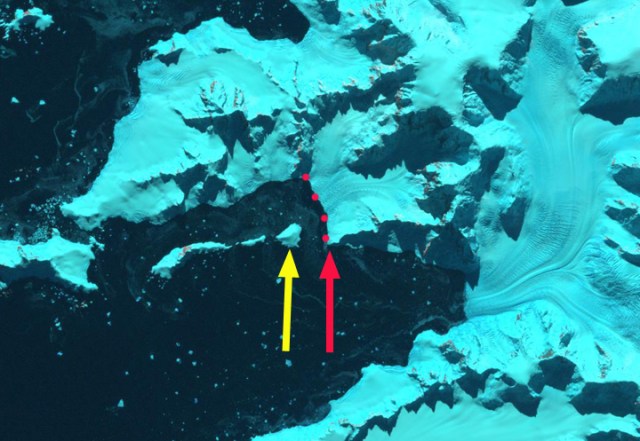

Type 1: Northern, with Large Floating Termini

Northern glaciers with large floating termini (Petermann, Ryder, Steensby, Zachariae, Academy, etc). Each of these is a marine terminating outlet glacier that has an extensive floating ice shelf. The large ice shelves can exist in part due to the lower surface melt rates and the lower flow rates of the glacier. Petermann Glacier is the fastest with a flow speed of 1000 m/year at the grounding line. This is much less than the average outlet glacier speed along the west coast. The large floating ice shelves are susceptible to bottom melting but, except for Petermann Glacier, we have no observations of the process or that more warm water is penetrating under these ice shelves. Rignot and Steffen (2008) found that at Petermann Glacier 80% of the ice loss into the ocean was from basal melting of the floating tongue. If the ice shelves are removed, the feeding glacier is less buttressed and will accelerate for a period and draw down its surface profile. The recent ice area lost by Petermann, Steensby, Academy and Zachariae Ice Stream indicate these glaciers are being impacted by the increased melting at the surface and likely the base of the ice shelf for Petermann Glacier at least.

Examination of how far the high velocities extend inland in Figure 2 and 3 indicates that it is only Zachariae and Petermann that tap far into the ice sheet. This northern area has low accumulation rates, and a shorter less intense melt season. The early onset of melting and lack of accumulation in 2010 led to an early exposure of the ablation zone on these glaciers. This is their sensitivity Achilles Heel: relatively little increases in melt can expand the ablation zone appreciably given the low surface slopes and low accumulation rates. Based on the velocity map, it is the Zachariae that is likely the only of this group that would be comparable to a bank that is too big to fail as its increased velocity band extends well into the ice sheet (Joughin et al, 2010).

Figure 1. Velocity of Petermann and Humboldt Glacier, the latter does not have a deep bedrock trough extending to the heart of the GIS.

Fig 2. Ice flow speed for Zachariae Glacier (Joughin et al, 2010)

Type 2: Inland-terminating

Glaciers with inland termini lacking any calving (Sukkertoppen, Frederickshaab, Russell, etc). Between the fast flowing marine terminating outlet glaciers, the ice sheet particularly in the southwest quadrant has numerous glaciers that terminate on land or in small lakes. The velocity of these glaciers reaches a maximum of 1-2 meters/day. Each terminates on land because total ablation over the glacier equals total accumulation at the terminus. These glaciers are more like a typical alpine glacier and are susceptible to the forces that tend to cause alpine glaciers to experience peak flow during spring and early summer. Those forces are the delivery of meltwater to the base of the glacier, when a basal conduit system is poorly developed. This leads to high basal water pressure, which enhances sliding. As the conduit system develops the basal water pressure declines as does sliding, even with more water. In the long run it is not clear that more melt will lead to sustained higher velocities as a more efficient drainage system leads to lower basal water pressures. Sundal et al, (2011), best illustrated this.

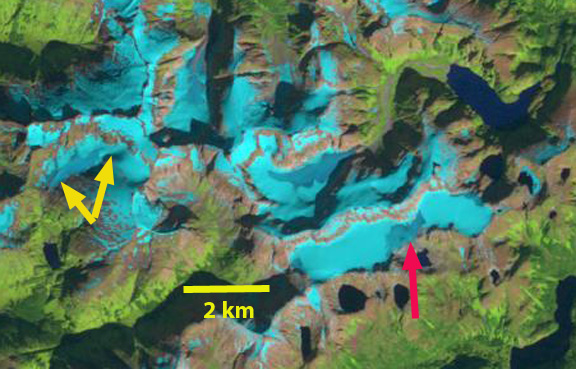

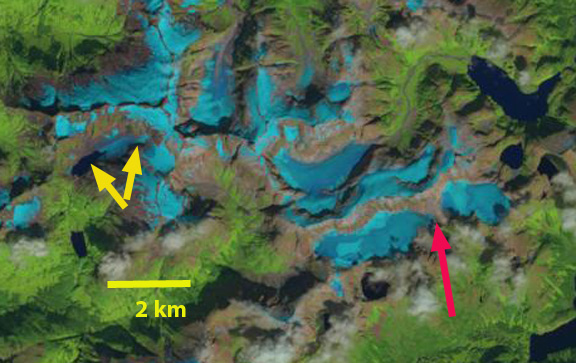

Fig 3. An example of a two-dimensional ice-velocity map of the study area in southwest Greenland Inland terminating glaciers velocities (Sundal et al, 2011).

This is what has been recently reported to be the case by Sundal et al (2011). The meltwater lubrication mechanism is real, but as observed is limited both in time and area impacted. It is likely that, as on alpine glaciers, the seasonal speedup is offset by a greater slowdown late in the melt season. Most observed acceleration due to high meltwater input has been on the order of several weeks, leading to a 10-20% flow increase for that period. The role of supraglacial lakes in this has been a point of emphasis; Luthje et al, (2006) noted that the area covered by supraglacial lakes was independent of the summer melt rate, but controlled by topography. This led Luthje et al (2006) to conclude that the area covered by supraglacial lakes will remain constant even in a warmer climate. This suggests that the enhancement of flow by the drainage of such lakes would be limited.

The land terminating glaciers such as Sukkertoppen, Russell and Mittivakkat are retreating significantly in response to global warming. This is an indication of negative mass balance. The latter glacier in southeast Greenland has retreated 1200 meters since 1931 (Mernild et al, 2011). The Mernild study identified this slow rate compared to the outlet glaciers and, based on mass balance observations, that the current surface mass balance can only support a glacier at most one-third its current size. This indicates the slow but inexorable sensitivity of the non-calving glacier to surface mass balance change. Moon and Joughin (2008) observed that the retreat of the land terminating glaciers was relatively minor from 1992-2007, averaging 5 m/year or less. These glaciers are the equivalent in our banking system to the local banks: there are many and they are sensitive, but the changes in a single one is not important.

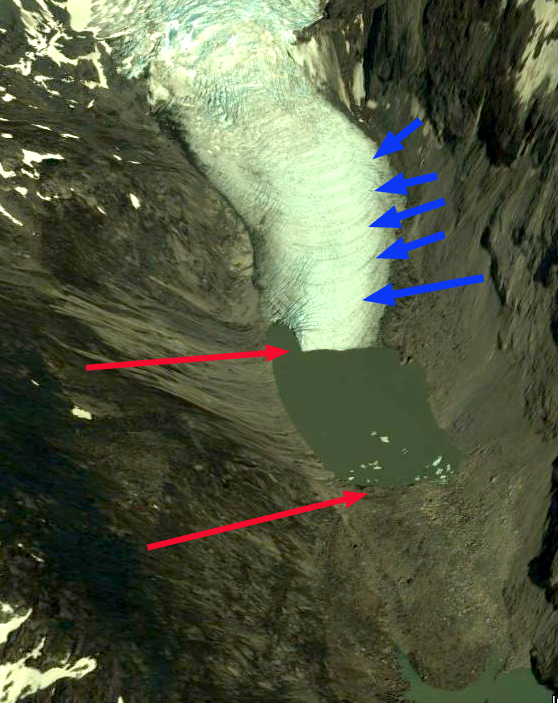

Type 3: Marine-terminating

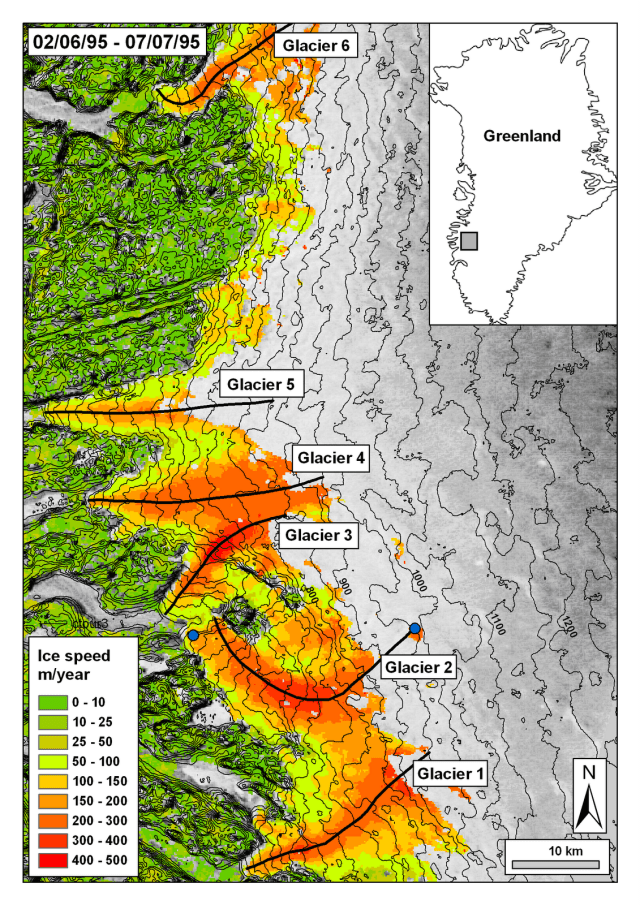

Fast flowing marine terminating outlet glaciers of western and southeast Greenland (Rinks, Umiamako, Helheim, Jakobshavn, Epiq Sermia, etc). These are the glaciers that drain the greatest area of the ice sheet and deliver the greatest volume to the oceans via calving. The flux from many of the larger glaciers is over 10 km3/year (DMI). Each of these glaciers is fast-flowing at the terminus; the fast flow section extends inland into the ice sheet up a sub-glacial trough. The outlet glaciers act like a drain capturing ice from a larger area of the ice sheet than their narrow terminus would suggest.

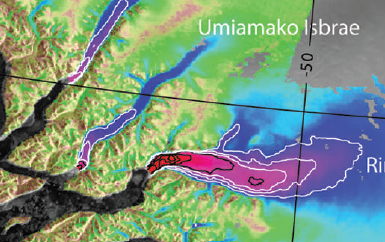

Figure 4. Umiamako Glacier is typical with the highest velocity near the calving front and the high velocity ice stream extending back into the ice sheet.

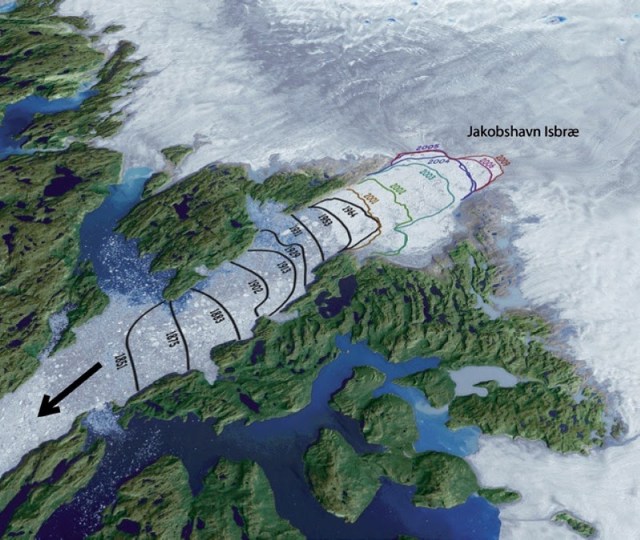

Figure 5. Jakobshavn Glacier terminus retreat, the recent retreat has been associated with thinning and faster flow.

Pelto et al (1989), a paper on the equilibrium state of the Jakobshavn Glacier, showed that the terminus had not changed significantly in 30 years; its velocity had also been consistent. Furthermore, it was observed that the velocity was consistent throughout the seasons. This indicated that the glacier velocity was not being impacted by the meltwater pulse each summer.

Bob Thomas (NASA, 2004) and Terry Hughes (University of Maine, 1986) developed the basic mechanism of flow for the glacier that has proven to be true. The outlet glaciers have a balance of forces at the calving front. The fjord walls, the fjord base and the water column impede flow. The slope of the glacier, its upglacier velocity and the height of the calving face strive to increase flow. If the glacier thins than there is less friction at the calving front from the fjord walls and the fjord base, leading to greater flow. The enhanced flow leads to retreat and further thinning, resulting in the thinning and the acceleration spreading inland. In 1990 it was not envisioned that acceleration would occur as soon as it has, yet that was the motivation for the research.

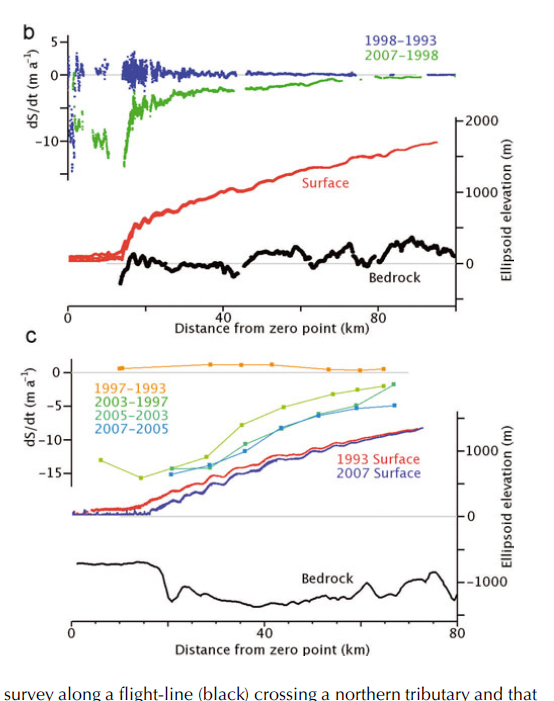

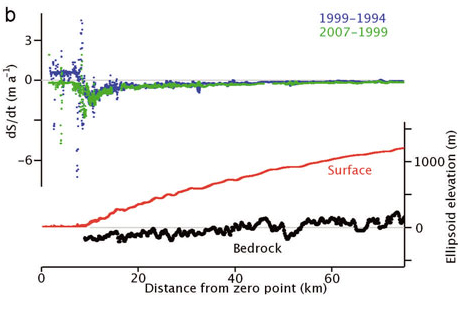

Fig 6. Jakobshavn profile (Thomas et al, 2009)

In 2001 acceleration of Helheim, Jakobshavn and Kangerdlussaq Glacier caught the attention of the world. By 2007, acceleration had been noted at all 34 marine terminating outlet glaciers observed.

The acceleration was not significantly seasonal; Howat et al (2010) noted a 15% seasonal component to the acceleration, it had spread inland and had led to retreat and thinning. This demonstrated that the marine terminating glaciers were largely responding to a change in the balance of forces at the glacier front.

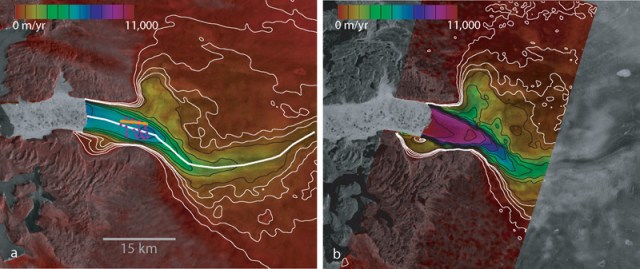

Fig 7. Ice flow velocity as color over SAR amplitude imagery of Jakobshavn Isbræ in a) February 1992 b) October 2000. In addition to color, speed is contoured with thin black lines at 1000 m/yr intervals and with thin white lines at 200, 400, 600, and 800 m/yr. Note how the ice front has calved back several kilometers from 1992 to 2000. Further retreat in subsequent years caused the glaciers speed to increase to 12,600 m/yr near the front. (Ian Joughlin, Big Ice)

The recent increases in outlet glacier discharge have always been coincident with partially floating ice tongue losses. This causes reduced back pressure at the glacier front, letting up on the brakes; the resulting glacier thinning leads to less basal friction and further acceleration. If the glacier front retreats into deeper water the process will continue and increase. This is why understanding the basal slope changes inland of the calving fronts is crucial. Moon and Joughin (2008) observed the terminus change of 203 glaciers from 1992-2007 and noted a synchronous ice sheet wide retreat of tidewater outlet glaciers. The thinning could be due to increased surface melt, basal melt or most likely a combination of the two. Certainly the supraglacial lake drainages are not the key as the widespread acceleration in the southeast and southwest Greenland, yet the southeast has less than 10% of the lakes of the southwest , as documented by Selmes et al (2013) in a paper submitted to the Cryosphere.

Moon and Joughin (2008) reported for the 2000-2006 period:In the southeast quadrant 35 glaciers retreated an average of 174 m/year. In the eastern quadrant 21 glacier retreated an average of 106 m/year. In the northwest 64 glaciers retreated an average of 118 m/year. Each quadrant’s retreat increased markedly after 2000. In east central Greenland Walsh et al (2012) noted the retreat of all 37 outlet glaciers examined. Bjork et al (2012) note the terminus change in 134 east Greenland glaciers, idenitifying the last decade as the most rapid for marine terminating glaciers but not land terminating glaciers. The largest of this group are comparable to the banks that are too big for our banking system to allow them to fail: they drain a substantial portion of the entire ice sheet and reach so far into the ice sheet that their behavior can impact that of other adjacent glaciers.

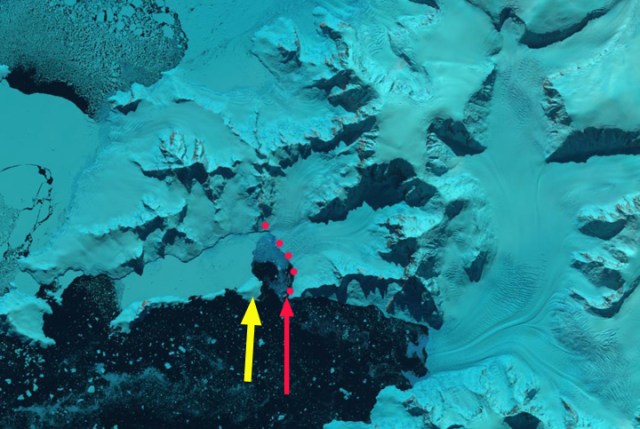

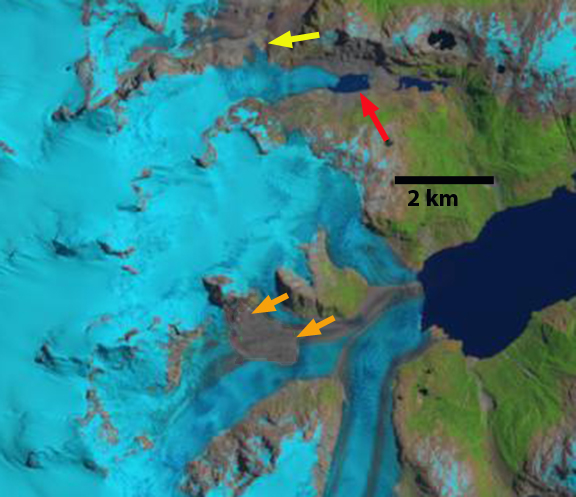

Type 4: Marine-terminating in Shallow Water

Marine terminating glaciers outlet glaciers in shallower water (Humboldt, Cornell, Steenstrup etc). These glaciers do have calving termini, but lack the large fast flowing feeder tongues extending into the glacier. This is because there is not a topographic low under the ice sheet that funnels the flow. Humboldt Glacier is the widest front of any Greenland Glacier, wider even than Petermann Glacier. However, the velocity on average is low at 100 m/year and the base of the glacier is quite high. This makes it difficult for a large calving retreat of the glacier to occur and extend inland. Humboldt Glacier is retreating but as the velocity profile indicates the glacier, despite its size, does not tap dynamically into the center of the ice sheet. These glaciers are substantial, but their failure (though significant for sea level) would not destabilize the ice sheet as a whole. Naarsap Sermia would be another example in southwest Greenland. Dodge and Storm Glacier an example in northwest Greenland.

Fig 8. Humboldt profile (Thomas et al, 2009)

The amazing aspect of Greenland glaciers is that (despite the specific variation in type, location specific fjord configuration, etc) their response has been as uniform and synchronous to global warming as has been observed. If this warming of the world persists long enough, the ice “banks” of Greenland will begin to fail. Those with the greatest reserves on their asset sheets and the fastest turnover, and thus having the greatest potential contributions to sea level rise over time, are: In the north, Zachariae (and to a lesser extent, Petermann). The fast flowing marine terminating outlet glaciers of western and southeast Greenland (Rinks, Umiamako, Helheim, Jakobshavn, Epiq Sermia and Kangerdlussaq).

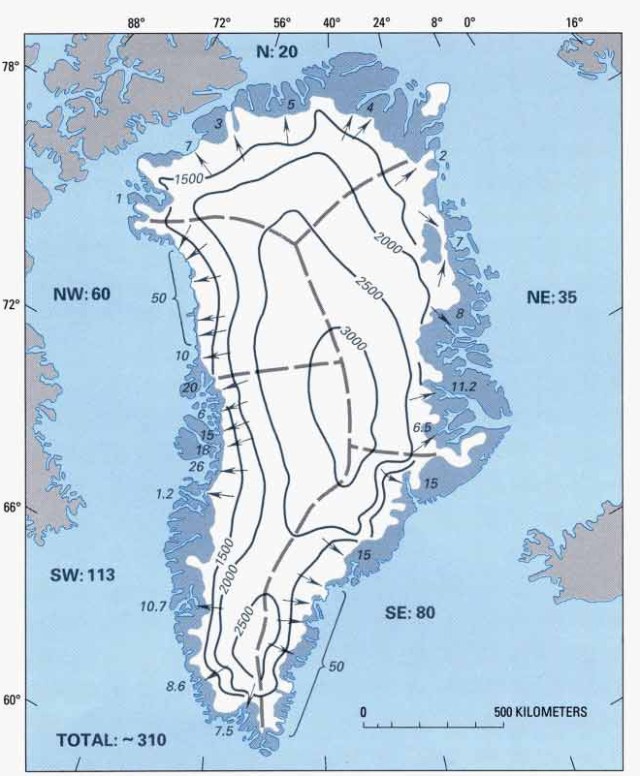

The surface mass balance of the glacier is the difference of accumulating snow on the ice sheet (its income) and snow and ice losses from melting and calving (its expenditures). The volume of the ice sheet is its asset. On an ice sheet, the main factor driving flow is simply the mass balance input in the accumulation zone. The higher the accumulation rate the faster the movement; the accumulated snow is inexorably moved downslope towards the ocean and the margin of the ice sheet. Observation of a precipitation map (focused not on the outer margin, but on the accumulation zone of the ice sheet) indicates that highest accumulation rates, over 40 cm per year, extend along the western side of the ice sheet to the southeast quadrant of the ice sheet. The southeast quadrant also has many fewer surface lakes than the southwest quadrant.

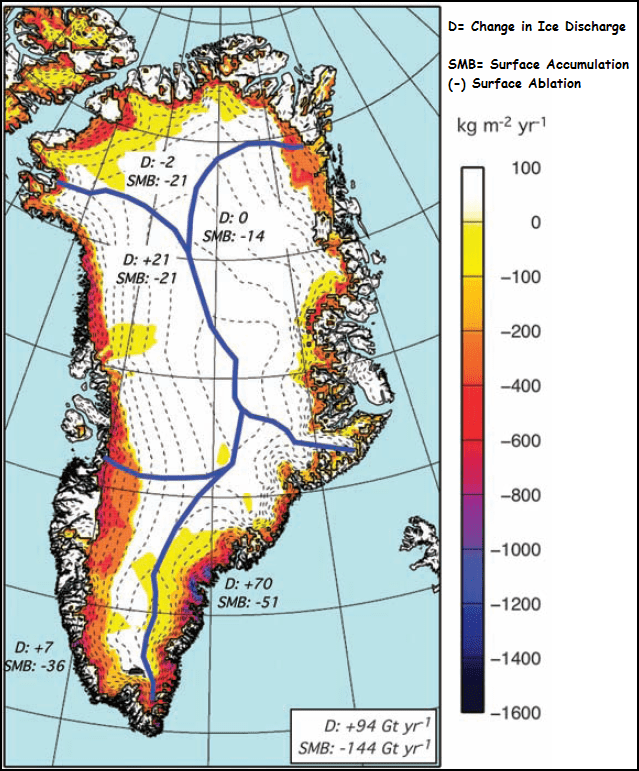

Figure 9. Mass balance in Greenland from Van Den Broecke et al, (2009)D denotes change in ice discharge while SMB denotes the net surface mass balance (accumulation minus ablation).)

Fig 10. Distribution of precipitation in Greenland (in grams per square centimeter per year). Contours dashed where inferred. Ice-free areas are shown in dark gray. (USGS, Satellite Image Atlas of Greenland)

The overall topography of the ice sheet is controlled both by the basal and peripheral geology and the mass balance distribution of the ice sheet. The higher rates of mass accumulation inland and the greater melting nearer the margin yield a steeper profile for the ice sheet.

Figure 11 shows that the contours have the closest spacing along the west margin and in the southeast, just as the high accumulation rates in those areas would suggest. Thus the combination of the surface slope and the accumulation rate drive faster flow in these regions.

Climate change has led to an observed increase in surface melting, surface accumulation, increased discharge and overall mass balance losses. The very mechanism that establishes the basics of behavior of the GIS mass balance are changing (Zwally et al, 2011). This is leading to most Greenland glaciers retreating, most outlet glaciers accelerating, an increase in the number and elevation of Greenland lake, expanding melt extent on the ice sheet. The 2012 seasons extraordinary ice melt extent is illustrated by the video below of Marco Tedesco’s melt extent data set. .