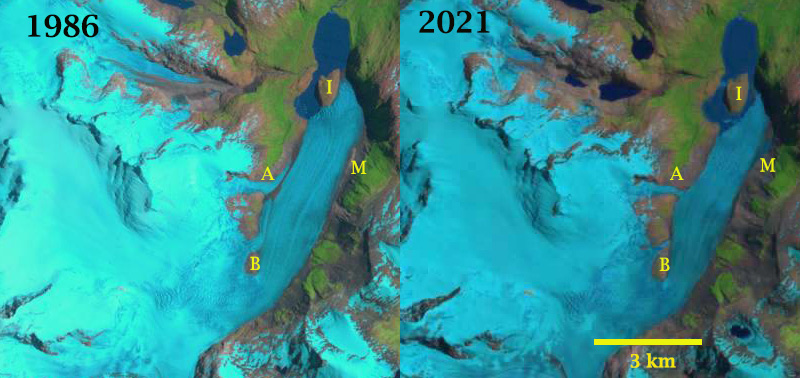

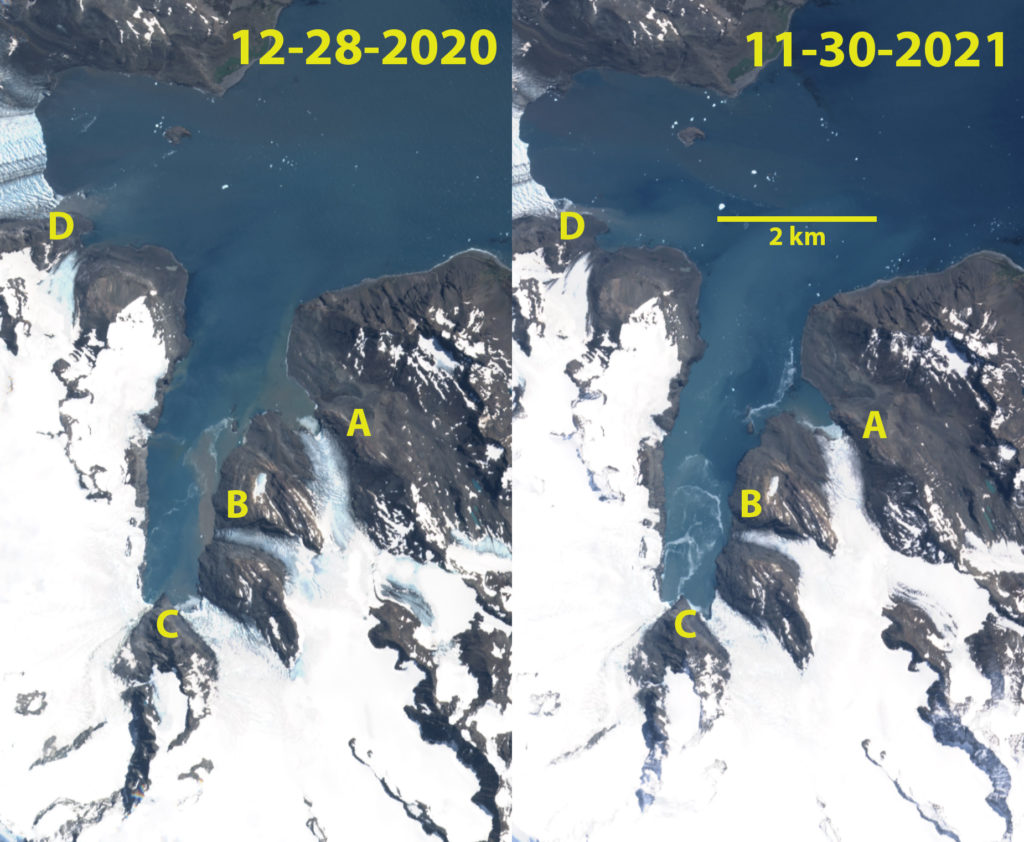

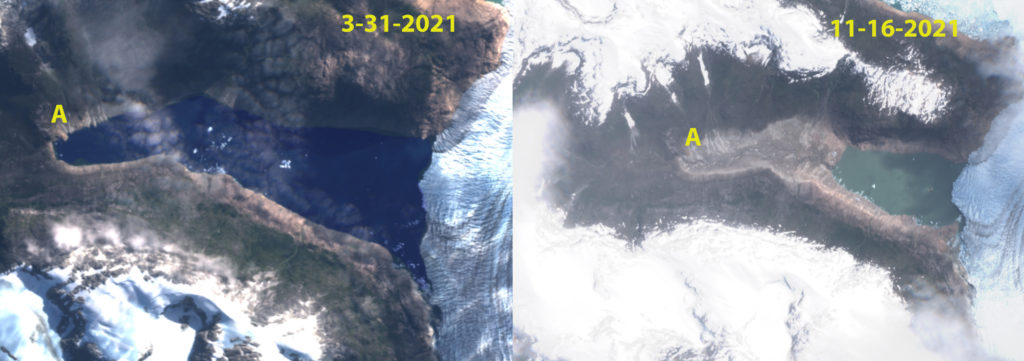

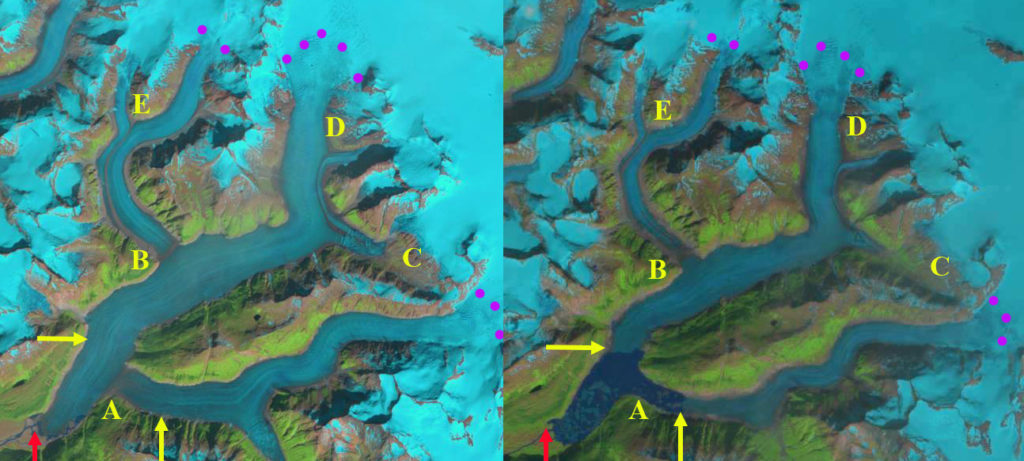

Changsang Glacier in Landsat images from 1989 and 2021, illustrating a 2.05 km retreat from 1989 terminus position-red arrow to the 2021 terminus position-yellow arrow. Formation of a new lake is also evident. The snowline is marked by purple dots.

Changsang Glacier (Karda Glacier) is a valley glacier just north of Kanchengjunga, Nepal/Sikkim. A comparison of Landsat imagery from 1989 to 2021 identifies the formation of a lake at the end of the glacier.

The Changsang Glacier was reported to be retreating 22 m/year from 1976 to 2005 (Raina, 2009). Shukla et al (2018) inventoried lakes in Sikkim during the 1975-2017 period and found 35 proglacial lakes in contact with a glacier in 2017. The number and area of these lakes had increased 34% and 90% respectively during this period. One of the rapidly expanding lakes is at Changsang Glacier.

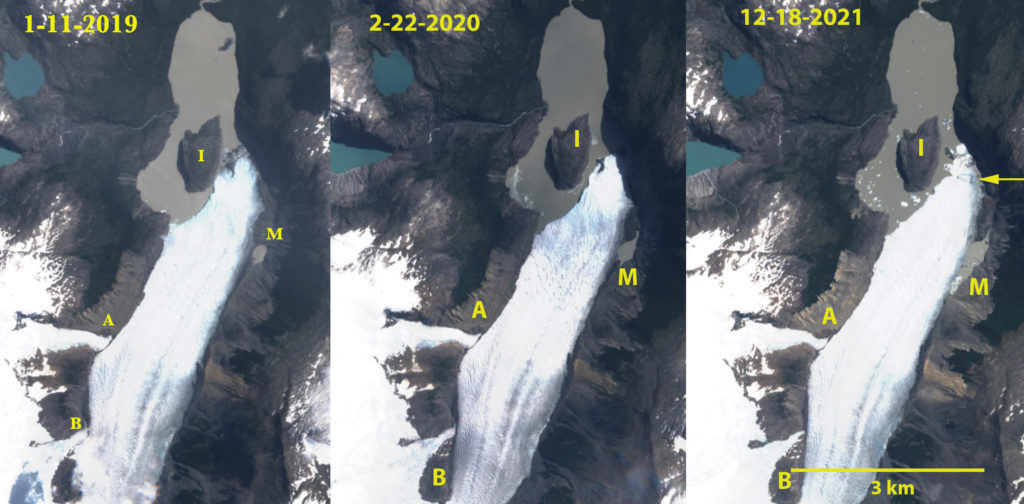

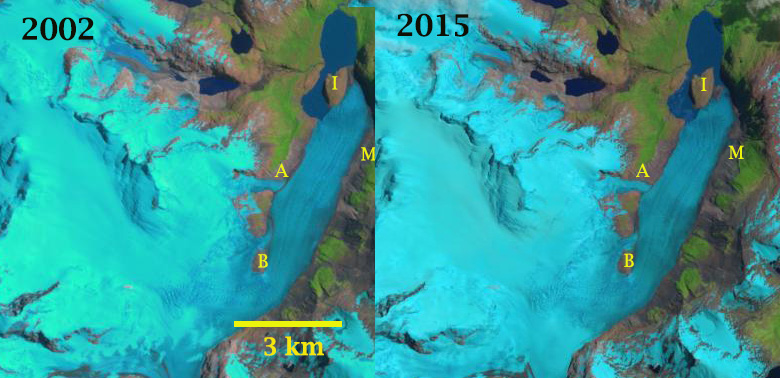

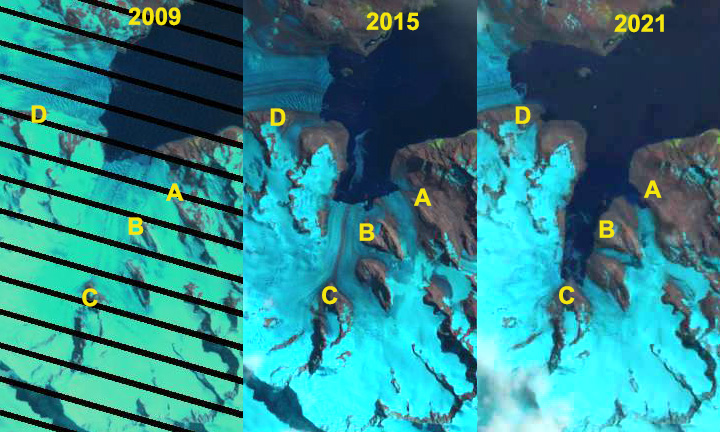

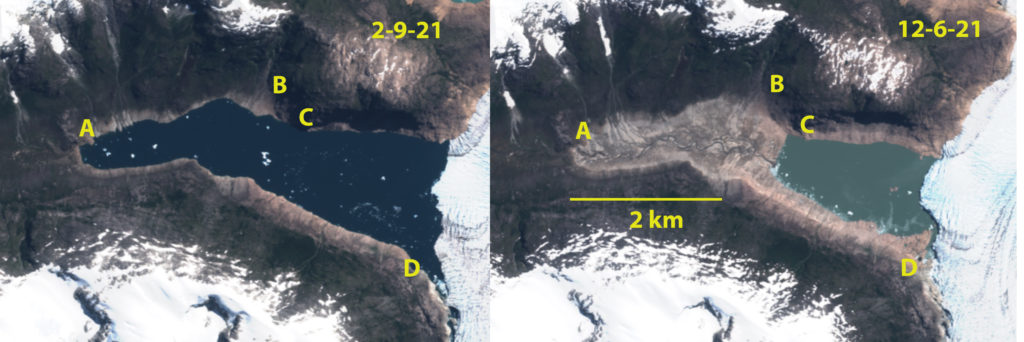

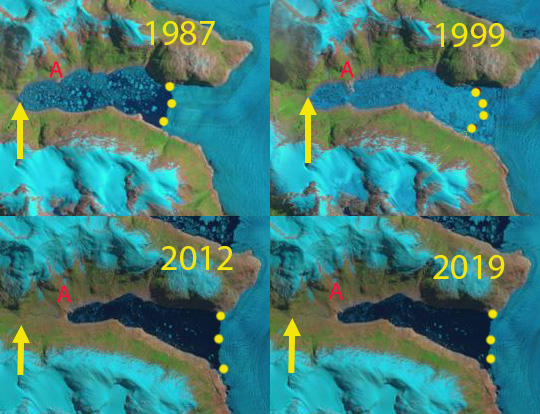

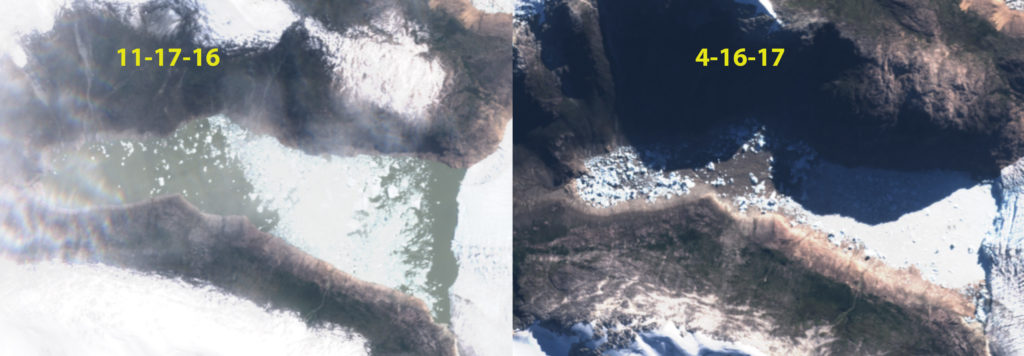

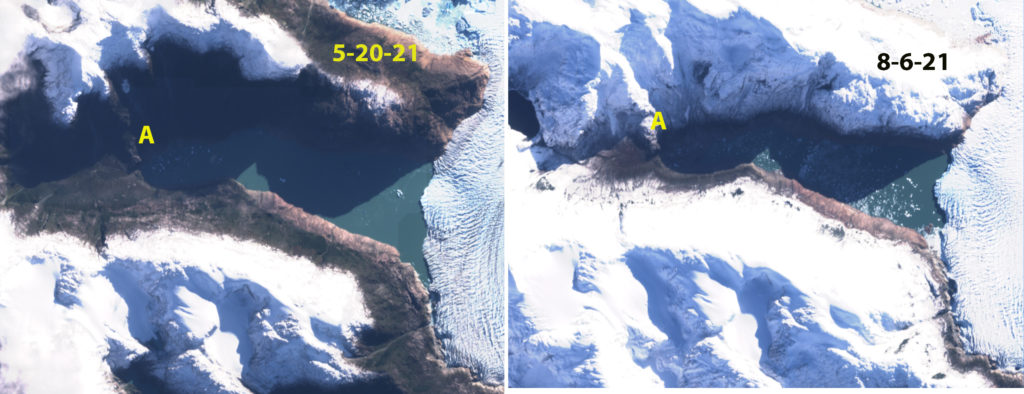

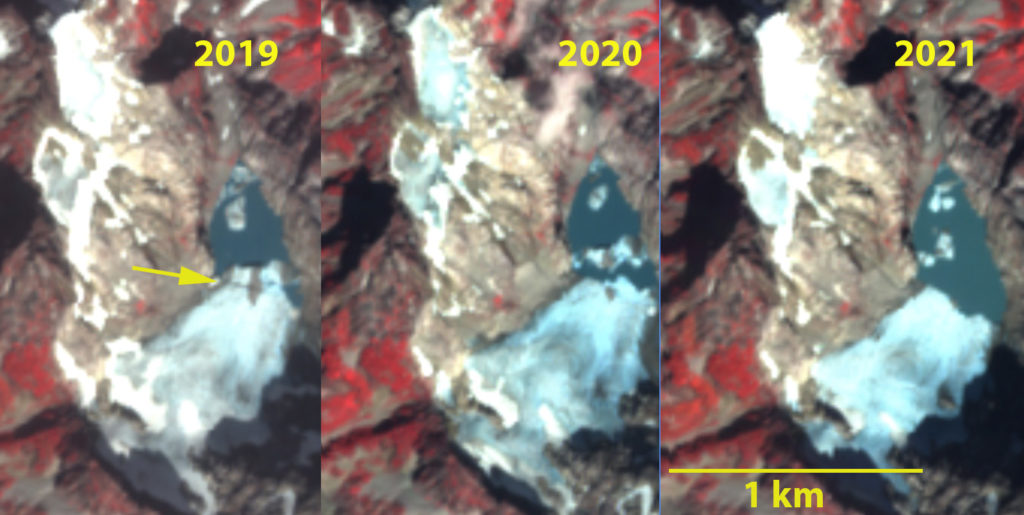

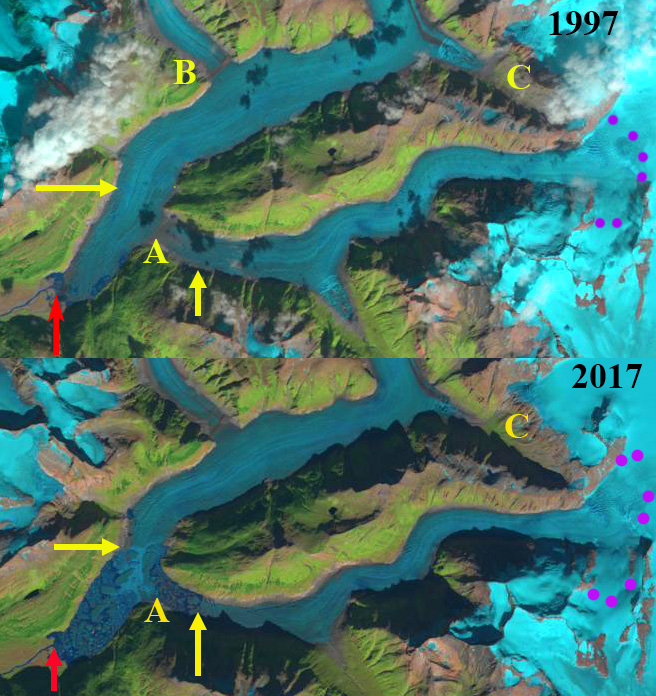

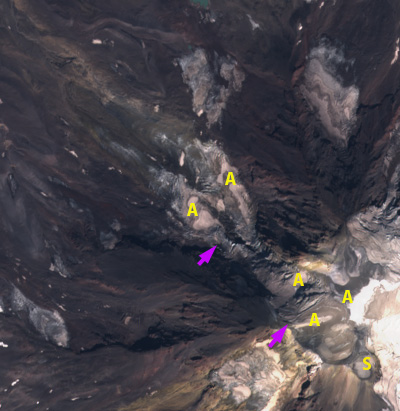

In 1989 there is no evidence of a significant lake either on top of the glacier-supraglacial or proglacial, at the end of the glacier. In 2000 there are a several small lakes beginning to develop with a combined area of 0.22 km2 (Shukla et al., 2018), the snowline is at 5650-5700 m. In 2002 the supraglacial lakes are noticably more connected, and the snowline is at 5700 m in mid-December . By 2011 the main lake is 1000 meters long and has one debris covered ridge that separates it from a second lake. By 2015 the lake has expanded incorporated the second lake and is now 1600 meters long with an area of 0.70 km2 . The snowline is notably high at 6000 m in mid-October . On Christmas Day 2020 the snowline is particularly high at 6100 m, reflecting the warm post-monsoon early winter period observed at Mount Everest last year (Pelto et al , 2021). In December 2021 the proglacial lake at ~5400 m is 0.93 km2 and the glacier has retreated 2050 m since 1989. Lake expansion since 2015 has been slower. The lake is impounded by a 400 m wide moraine belt on the low slope valley floor beyond the lake margin, and does not appear to be a significant GLOF risk. The retreat of this glacier is similar to that of Kokthang Glacier and Middle Lhonak Glacier.

Changsang Glacier in Landsat images from 2000 and 2020 illustrating retreat from 1989 terminus position-red arrow to the 2021 terminus position-yellow arrow. Transition from small supraglacial lakes to a single proglacial Lake is evident. The snowline is marked by purple dots, which in late Deember 2020 reached 6100 m.

Changsang Glacier in Landsat images from 2002 and 2015 illustrating retreat from 1989 terminus position-red arrow to the 2021 terminus position-yellow arrow. Coalescing supraglacial lakes into a single proglacial lake is evident. The snowline is marked by purple dots which in October 2015 reached 6000 m.