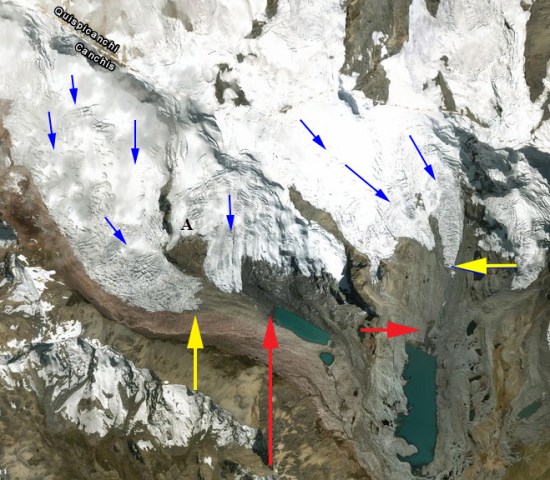

Three glaciers at the head of Sonderarm fjord in 1999 and 2018 Landsat images. Yellow arrows indicate terminus location in 2018 of each glacier, pink arrow indicates a separate valley glacier that has diminished.

Sonderarm is a fjord that extends south from Lindenow Fjord in southern Greenland. The glacier is a short distance east of Kangersuneq Qingordleq, where recent retreat has led to glacier separation and a just south of Norrearm where glacier retreat has led to fjord extension.

In 1999 the Eastern Sonderarm Glacier (ESG) extended beyond its inlet into Sonderarm. The Southern Sonderarm Glacier (SSG) extended to the end of its arm of the fjord. The Northern Sonderarm Glacier (NSG) terminated 600 m from the end of its arm of the fjord. At the pink arrow the separate valley glacier was just in contact with tidewater. By 2002 there was significant narrowing of the terminus front of ESG and the separate valley glacier no longer reaches tidewater. There is considerable calving in Sonderarm, with NSG appearing to be the most active. In 2017, the snowline is relatively high at 700-800 m in early August, there is limited calving evident in Sonderarm. By 2018 the retreat of NSG is 1100 m since 1999, of SSG 1300 m and of ESG 400 m with a significant reduction in the width of the calving front. The snowline in 2018 is again above 700 m in early August. There are no evident icebergs in Sonderarm. The separate valley glacier now terminates 300 m from tidewater. The reduction in calving accompanying retreat indicates that it is surface melt as indicated by higher snowlines that is driving retreat of the Sonderarm glaciers. NSG begins at 1200 m with only a limited area above 1000 m, while ESG and SSG begin at 1000 m.

Greenland tidewater outlet glaciers in this region have experienced substantial retreat since 1990 (Weidick et al 2012). Murray et al (2015) examined 199 tidewater glaciers in Greenland and noted significant retreat of 188 of them.

Three glaciers a the head of Sonderarm fjord in 2002 and 2017 Landsat images. Yellow arrows indicate terminus location in 2018 of each glacier and purple dots the snowline.

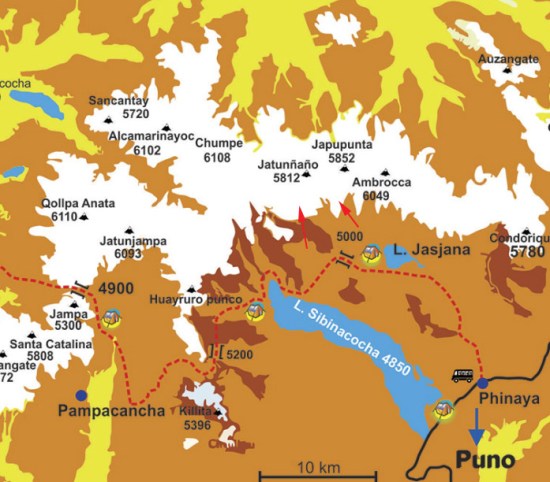

Sonderarm region map with glacier flow of the three Sonderarm glaciers in blue. Pink arrow indicates valley glacier that has diminished and formerly reached tidewater.