Snapshot of day 3 of Glaciology poster presentations at AGU. The amount of glaciology research is impressive, there is much we do not know. We can no longer say that we know very little about any aspect or region. Before saying that explore the vast literature that is now available.

Jeff La Freniere at Gustavus Adolphus College used several new technologies, aerial and terrestrial LIDAR and structure-from-motion photogrammetry from drones make mass balance measurements using geodetic approaches increasingly feasible in remote mountain locations like Volcán Chimborazo, Ecuador. The result combined with a unique, 5-meter resolution digital elevation model derived from 1997 aerial imagery, reveal the magnitude and spatial patterns of mass balance behavior over the past two decades. Above are the results they found more specifically that on the Hans Meyer Glacier terminus, the mean surface elevation change since 1997 has been nearly 3 m yr-1, while on the lower-elevation Reschreiter Glacier the mean elevation change has been approximately 1 m yr-1 .

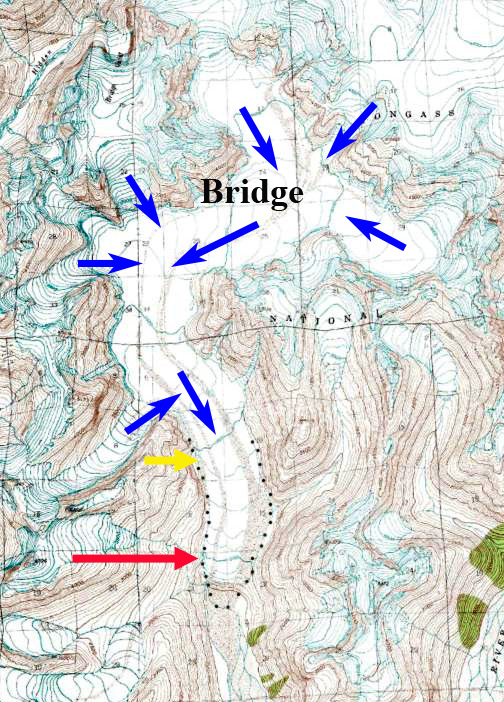

Aurora Roth, University of Alaska Fairbanks developed and applied a linear theory of orographic precipitation model to downscale precipitation to the Juneau Icefield region over the period 1979-2013. This LT model is a unique parameterization that requires knowing the snow fall speed and rain fall speed as tuning parameters to calculate cloud time delay. The downscaled precipitation pattern produced by the LT model captures the orographic precipitation pattern absent from the coarse resolution WRF and ERA-Interim precipitation fields. Key glaciological observations were used to calibrate the LT model. The results of the reference run showed reasonable agreement with the available glaciological measurements, which is what glacier mass balance observations have shown. The precipitation pattern produced was consistent regardless of horizontal resolution, and climate input data, but the precipitation amount varied strongly with these factors. The import is to help model mass loss from glaciers in Southeast Alaska which will alter downstream ecological systems as runoff patterns change.

Joanna Young, University of Alaska Fairbanks focuses on partitioning GRACE glacier mass changes from terrestrial water storage changes both seasonally and in long-term trends using the Juneau Icefield, which has long term glacier mass balance data, as a case study for . They leverage the modeling tool SnowModel to generate a time series of mass changes using assimilated field observations and airborne laser altimetry, and compare to GRACE solution from the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Geodesy Laboratory . This is one of the first to analyze GRACE at the sub-mountain range scale, and to examine terrestrial water storage trends at a smaller scale than the full Gulf of Alaska. The figure above looks at subannual and long-term changes of the Juneau Icefield from 2003 to present.

Emilio Ian Mateo, University of Denver Looked at rock glaciers in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado examining how slope aspect and rising air temperatures influenced the hydrological processes of streams below rock glaciers. Detailed findings illustrated above from 2016 and 2017 show that air temperature significantly influenced stream discharge below each rock glacier. Discharge and air temperature patterns indicate an air temperature threshold during late summer when rock glacier melt increased at a greater rate. The results suggest that slope aspect influences stream discharge, but temperature and precipitation are likely the most components of the melt regimes.

Maxime Litt, Utrecht University installed an eddy-correlation system (Campbell IRGASON) during a period of 15 days over the Lirung glacier in the Langtang Valley in Nepal , during the transition period between the monsoon and the dry season to examine surface energy balance. Results are also reported from Mera Glacier and Yala Glacier. At Lirung Glacier during the day, moderate winds blow up-valley and the atmospheric surface layer is unstable. Latent (sensible) heat fluxes scale between 50 and 150 (50 and 250) Wm– 2 during the day, thus drying and cooling the debris and significantly impact SEB. At night, weak down-glacier winds are observed and fluxes remain weak. Yala and Mera Glacier are different environments and illustrate the variations in position on SEB.

Katherine Strattman, University of Dayton reported on a study of the Imja, Lower Barun, and Thulagi Glaciers in the Nepal Himalaya. The retreat of the glaciers has led to proglacial lakes continuing to dramatically increase in area. They used Landsat, ASTER, and Sentinel satellite imagery to study the conditions of these glaciers. They assessed interannual changes in surface ice velocity from the early 1990s to present. They found both long-term and short-term velocity variations. Satellite imagery indicates the three lakes exhibit three contrasting trends of lake growth: Imja Lake has a strong accelerating growth history since the 1960s, Lower Barun a very slow accelerating growth, and Thulagi a decelerating growth, even as the glaciers of all three lakes have thinned. Above is the velocity of Barun Glacier showing velocity changes and growth of the lake.

Shashank Bhushan, Indian Institute of Technology Dhanbad developed a hazard assessment of moraine dammed glacial lakes in Sikkim Himalayas. They generated high-resolution DEMs using the open-source NASA Ames Stereo Pipeline (ASP) and other open-source tools to calculate surface velocity and patterns of glacier downwasting over time. Geodetic glacier mass balance was obtained for three periods using high-resolution WorldView/GeoEye stereo DEMs, Cartosat-1 stereo DEMs and SRTM. Initial results revealed a region-wide negative annual mass balance of -0.31± m w.eq. for the 2007-2015 period.