Guest Post by Ben Pelto, PhD Candidate, UNBC Geography, pelto@unbc.ca

As the summer ticks by and the fall glacier field season approaches, I’ve realized that I never put out a winter 2016-2017 synopsis, so, like the snowfall this year, it’s arrived late.

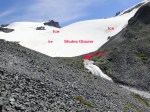

May 2017, Jesse Milner of the ACMG on the Nordic Glacier in front of the “meteor strike” a newly exposed rock face that spalls ice regularly. Photo by Ben Pelto.

May 2017, Jesse Milner of the ACMG on the Nordic Glacier in front of the “meteor strike” a newly exposed rock face that spalls ice regularly. Photo by Ben Pelto.

Story of the winter

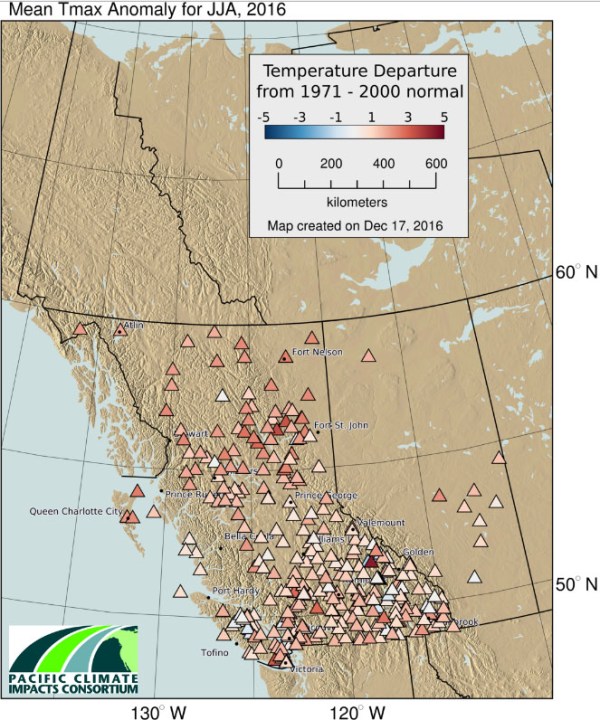

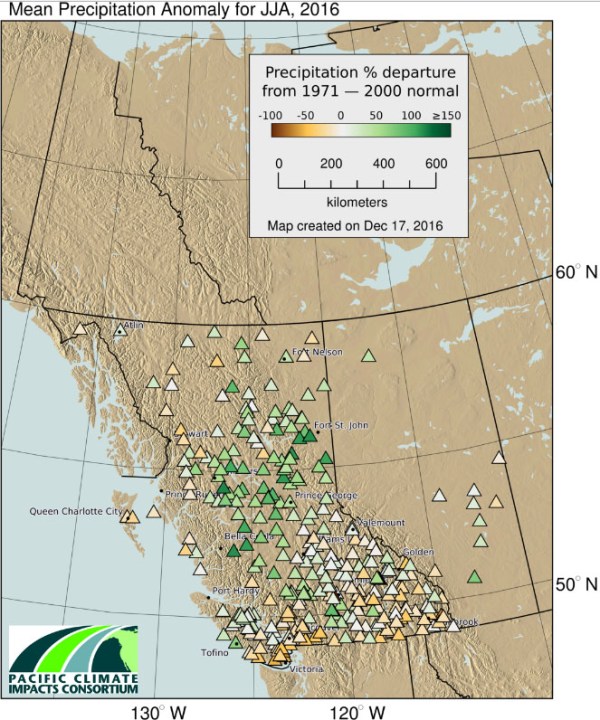

The winter began with an extremely warm November, featuring temperatures 2-5˚C above normal, with greater than average precipitation generally delivered via Pacific storm cycles. Arctic air masses moving south across BC dominated December, with a complete reversal of temperature to well below average temperatures (Figure 1), and drier conditions. By January 1st the BC River Forecast Center announced that the Columbia River Basin was at 80-88% of normal snowpack (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Maximum temperature anomaly for December 2016. Note Columbia Basin (SE BC) roughly 3˚C below normal (Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium).

Figure 1. Maximum temperature anomaly for December 2016. Note Columbia Basin (SE BC) roughly 3˚C below normal (Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium).

Figure 2. January 1st snow survey data from the BC River Forecast Center. The Columbia River Basin is comprised of the Upper Columbia, East Kootenay, and West Kootenay Basins, which range from 80-88% of normal.

Figure 2. January 1st snow survey data from the BC River Forecast Center. The Columbia River Basin is comprised of the Upper Columbia, East Kootenay, and West Kootenay Basins, which range from 80-88% of normal.

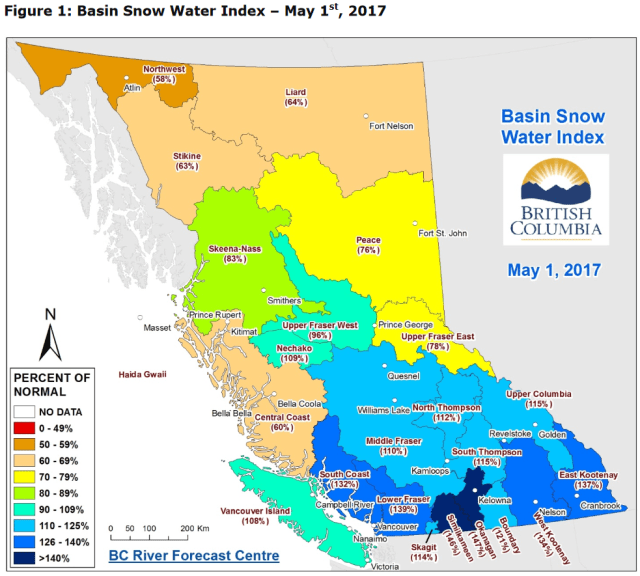

March and April brought cool and moist unstable conditions, leading to a significant increase in snowpack across southern BC, delaying the onset of the melt season by about two weeks. Snowpack measures for the basin were over 100% of normal for the first time of the winter; by May 1st, the Columbia Basin was at 115% of normal to the north and 135% in the south (Figure 3). By the first week of May, most regions had transitioned into the melt season, though at low to mid-elevations (below 1500 m) much of the snow had already melted.

Figure 3. May 1st snow survey data from the BC River Forecast Center. The Columbia River Basin is comprised of the Upper Columbia, East Kootenay, and West Kootenay Basins, which ranged from 115 to 137% of normal.

Figure 3. May 1st snow survey data from the BC River Forecast Center. The Columbia River Basin is comprised of the Upper Columbia, East Kootenay, and West Kootenay Basins, which ranged from 115 to 137% of normal.

Questions of alpine snowpack conditions

A trend seen over the past few winters is minimal to no snow at lower elevations with significant snow remaining higher, and it’s a pattern expected to continue in an era of rising temperatures leading to both rain on snow, and melt events through the winter. Unfortunately, current measurements, including the network of 70 automatic snow weather stations (ASWS) across the province, are all located at or below 2000 m. This leaves the alpine largely un-sampled. Rising temperatures may well be increasing the balance gradient of winter snow accumulation; that is, there will be a greater rate of change (increase) in snowpack with elevation than previously experienced, though data for this shift is lacking.

Our glacier research program

This information gap of alpine snowpack across BC is being addressed within the context of our glacier mass balance network funded by the Columbia Basin Trust. Each year we have been studying a series of five glaciers across the Basin, which from north to south are the Zillmer Glacier (Valemount), Nordic Glacier (northern boundary of Glacier National Park), Illecillewaet Glacier (Parks Canada, Rodgers Pass, Glacier National Park), Conrad Glacier (Golden, northern boundary of Bugaboo Provincial Park), and the Kokanee Glacier (Nelson, Kokanee Glacier Provincial Park). For more background see previous posts here and here.

Our spring field season consists primarily of snow depth measurements and snow density measurements, used to determine the snow water equivalent (SWE) retained on each glacier at the winter’s end. We also conduct GPS surveys of the glacier height, which we use to account for any surface height change between field visits, and the subsequent airborne laser altimetry surveys (LiDAR)of each glacier and the surrounding area that we’re conducting every spring and fall for the five years of the project.

May 2017, Pulling the ground penetrating radar up the Kokanee Glacier to measure ice thickness. The Kokanee is 20-80 m thick, averaging around 30-40 m. Photo by Rachael Roussin.

Our LiDAR data allows us to calculate snow depth by comparing a fall LiDAR-derived digital elevation model (DEM) to our spring DEM. Off-glacier, the fall DEM represents bare earth, and on glacier, the glacier surface at the end of the melt season. The spring DEM thus captures the fall surface height plus the winter snowpack. The difference in height between the two is taken to be accumulated snow. While our manual snow depth and density surveys of the five study glaciers are incredibly valuable data, our LiDAR surveys cover roughly 10% of the Columbia Basin glacier area, a more than three-fold increase. This expanded footprint allows a better picture of alpine snowpack across the province at elevations largely un-sampled; highly important to downstream concerns such as spring flooding and snow available for summer streamflow.

Fires and Floods

Dramatic swings of weather patterns characterized the 2016-2017 winter, with snowpack well below average in February and early March for the province. By the end of April, snowpack across the Columbia Basin and southern half of the province had rebounded to average or record levels depending upon location with Vancouver and the lower mainland receiving significant snowfall to much fanfare.

The late and cool spring saved the snow season, but also led to flooding across the province, particularly throughout the Okanogan and around Kelowna. As the wildfire season began in earnest, sandbags were still in place in Kelowna to protect properties against flooding from Okanogan Lake, which remained above full pool by 38 cms on July 10th. Wildfire crews had been tasked with fighting the flooding, and were removing many sandbags as lake levels began to fall before heading off to respond to escalating fires. The flooding began following a rapid warm-up combined with heavy rainfall that led to extreme avalanche risk and activity, with highway closures along the Trans-Canada and Icefields Parkway.

The record snowpack across the southern-most Columbia Basin such as around Nelson, BC, has long since disappeared, with Nelson implementing water restrictions to attempt to cut water usage by 50% in response to the rapidly diminishing snowpack which feed the town’s water supplies.

Forest fires have been raging over the province, burning an area larger than Prince Edward Island, in what is the worst fire season in BC since 1958. Forest fire impact on glaciers is largely unknown, as soot and ash from the fires may raise albedo, but smoke clouds reflect incoming solar radiation. One thing is for certain however, should the fires cloud the skies during our field season, spending 24 hours a day in fire smoke makes for a tough go.

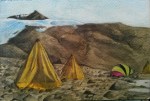

Team members at the foot of a recent avalanche preparing to head up to the Nordic Glacier in the first week of May 2017. Photo by Alex Bevington

Outlook

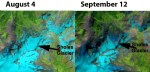

With our fall field season (August 19-September 21) only a week away, it will be an interesting time to observe how our study glaciers across the Columbia Mountains fared over this roller coaster of a year. After a cold, dry start to the winter, a late rally in March and April delayed the start of the melt season and raised snowpack to well above average across the Columbia Basin. A hot, dry summer led to flooding in May, and now wildfires in June-August, which reversed snowpack levels to below-average at most elevations. Satellite images of the study glaciers show rapidly rising snow lines, as above-average snow packs are reduced to average to below-average across most glaciers, with only the Kokanee Glacier appearing set for a possible positive mass balance year.

How do you get out? Jesse Milner at the bottom of a 5.5 m deep snow pit, which we use for sampling snow density. Nordic Glacier. Photo by Alex Bevington.

Clearly the area will still be beautiful and we will gain two new alpine lakes with the loss of the glacier. After making over 200 measurements in 2010 we completed a mass balance map of the glacier as we do each year. This summer we will be back again for the 32nd annual checkup. There will be likely be record low snowpack, comparable to 2005 the worst year from 1984-2014.

Clearly the area will still be beautiful and we will gain two new alpine lakes with the loss of the glacier. After making over 200 measurements in 2010 we completed a mass balance map of the glacier as we do each year. This summer we will be back again for the 32nd annual checkup. There will be likely be record low snowpack, comparable to 2005 the worst year from 1984-2014.