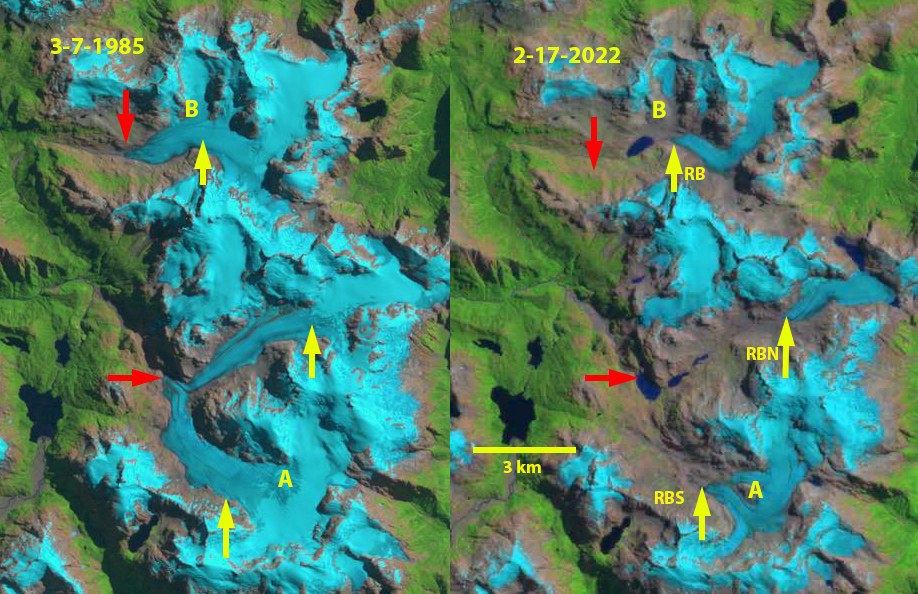

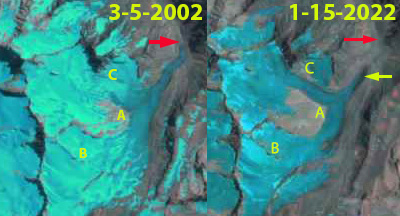

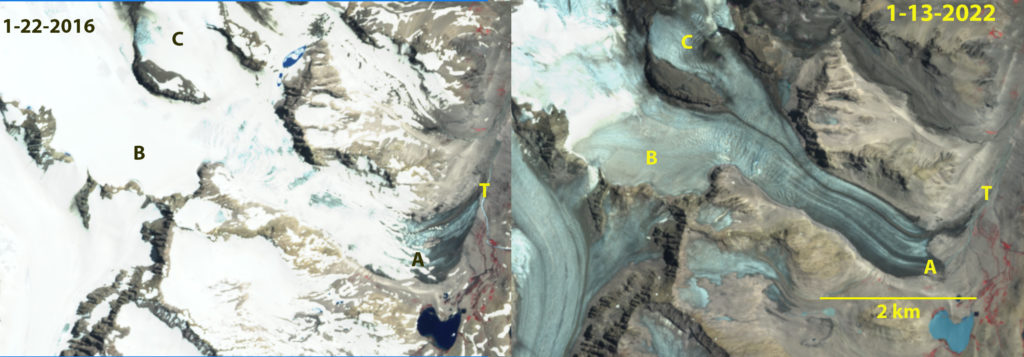

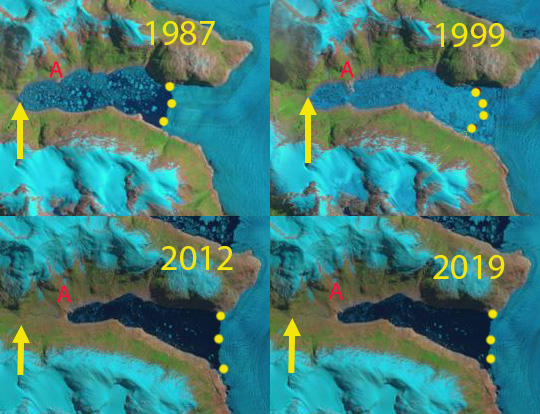

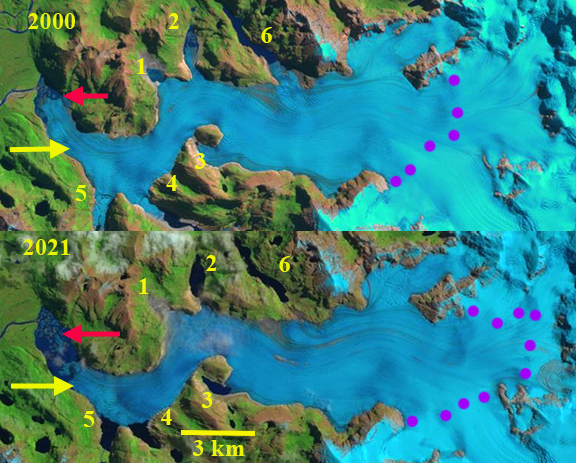

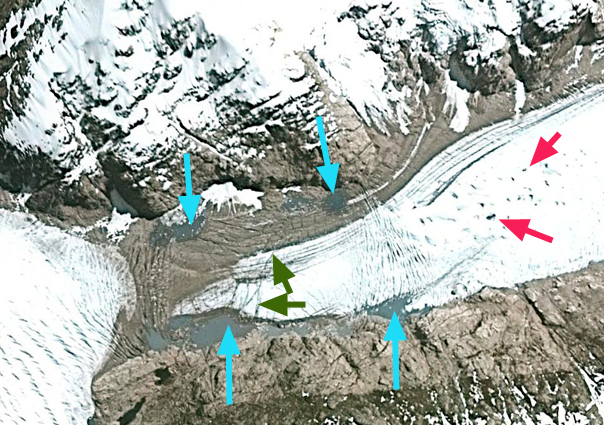

Rio Blanco Glaciers in Hornopirén Naitonal Park, Chile in Landsat 5 and 9 images from 1985 and 2022. Red arrows indicate 1985 terminus position, yellow arrows 2022 terminus position. Point A is an emerging bedrock nunatak and Point B is where tributary separation has occurred.

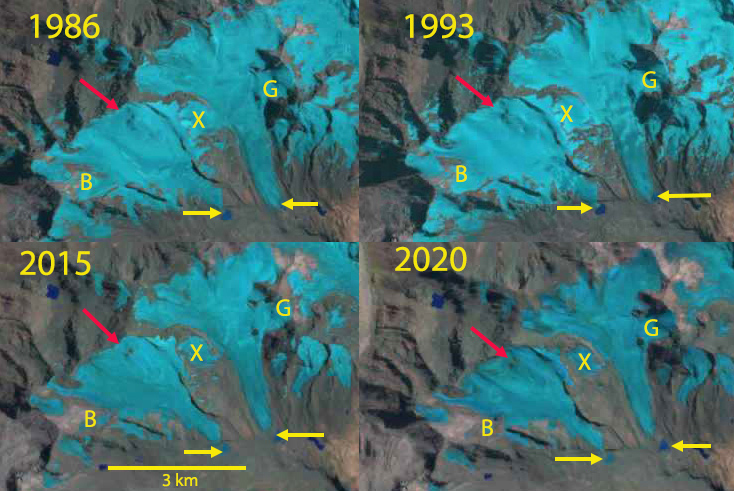

Hornopirén National Park is in the Los Lagos region of Chile. The park is host to a number of glaciers that are in rapid retreat. Davies and Glasser (2012) mapped the area of these glaciers with 113 km2 in 1986 and 96 km2 in 2011. The retreat of the largest glaciers in the park is spectacular in recent years.Barcaza et al (2017) indicate that Inexplorado glaciers have lost 0.46-0,48 km2 from 2003-2015. Here we examine Landsat imagery to identify changes in three of the larger valley glaciers from 1985-2022. These glaciers from the headwaters of the Rio Blanco and are designated Inexplorado (RB), Rio Blanco North (RBN), Rio Blanco South (RBS). Rio Blanco enters the ocean just east of the community of Hornopirén.

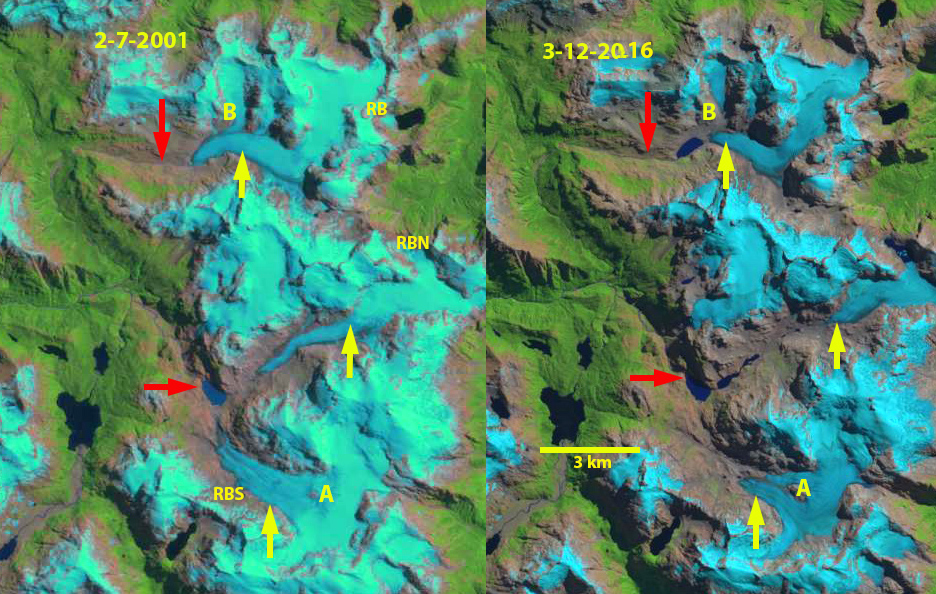

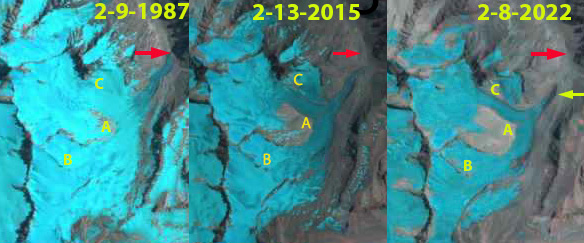

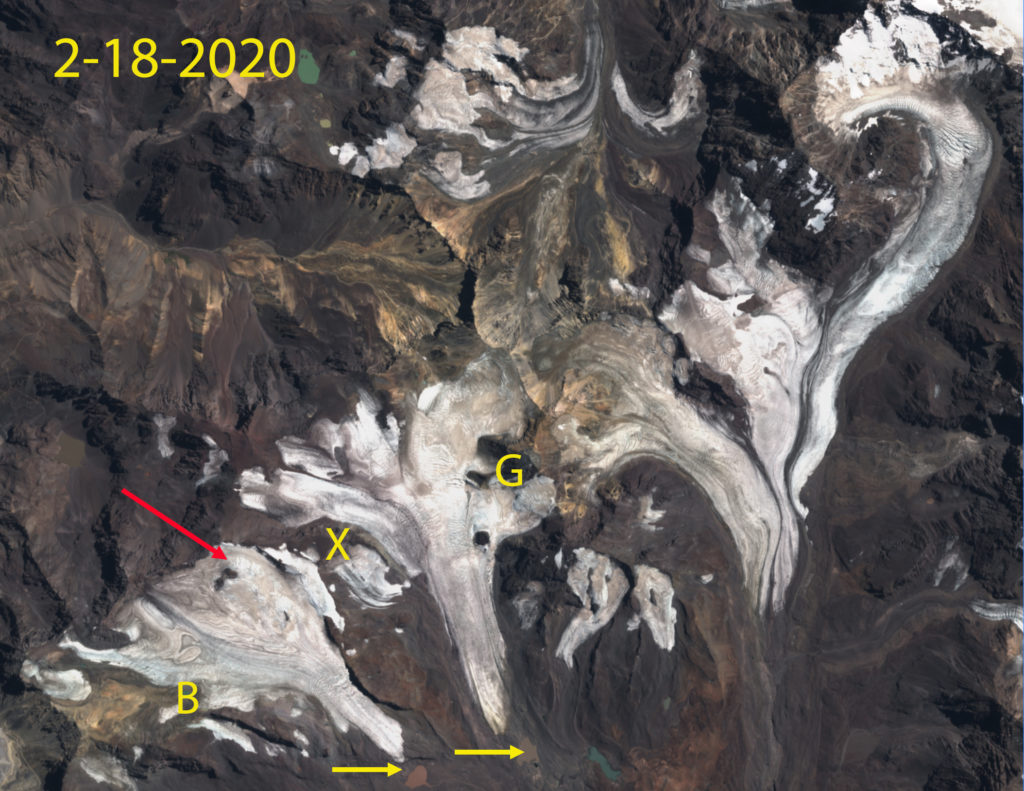

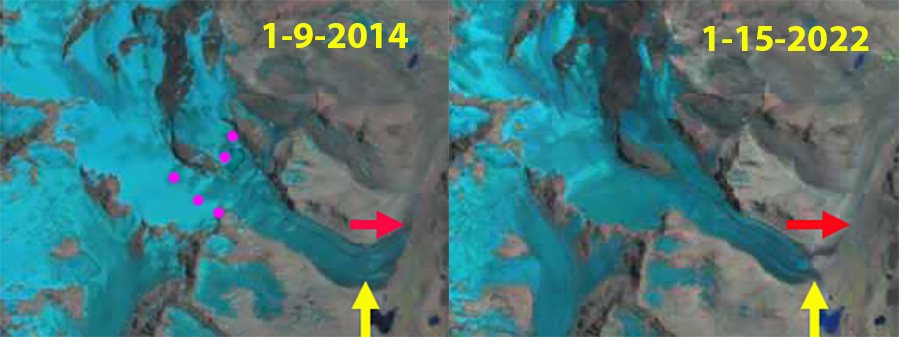

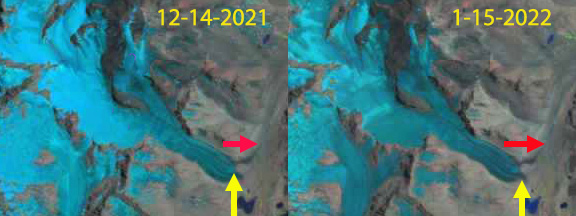

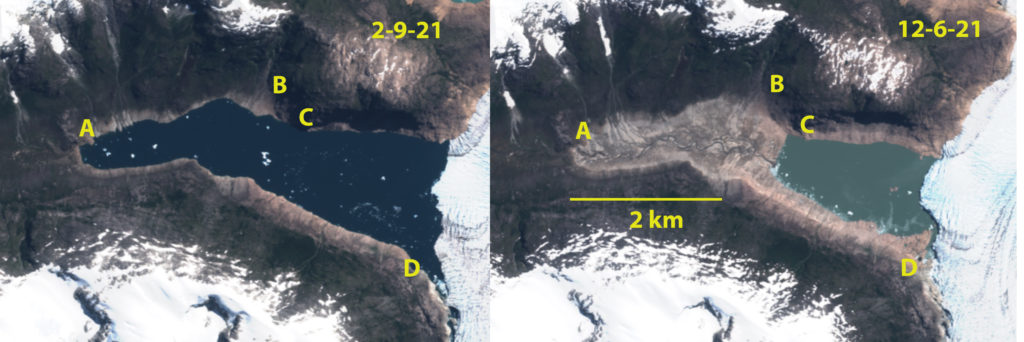

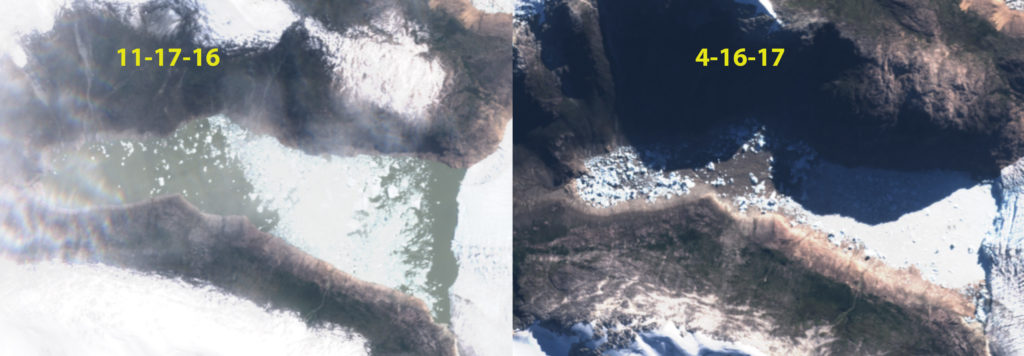

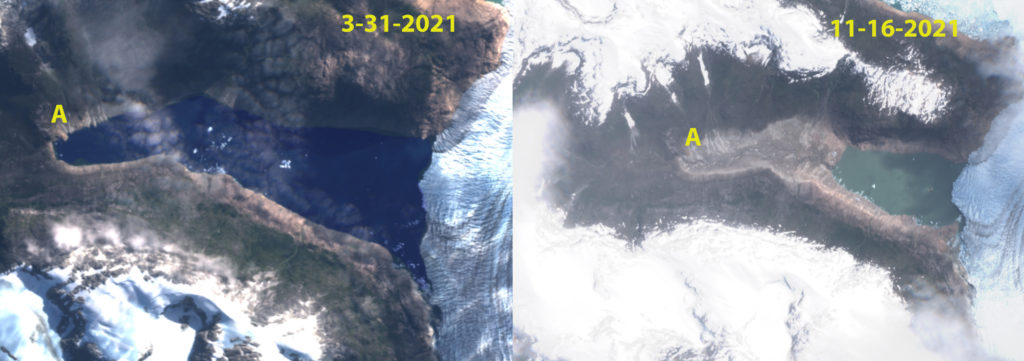

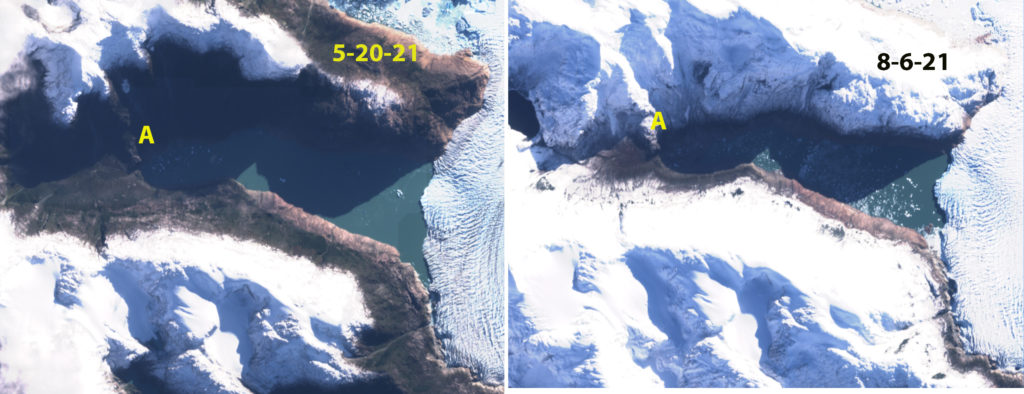

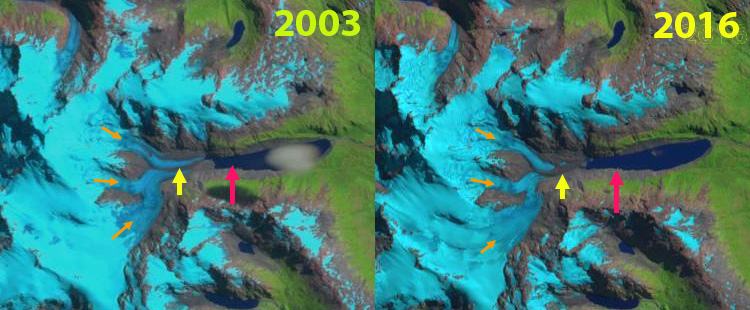

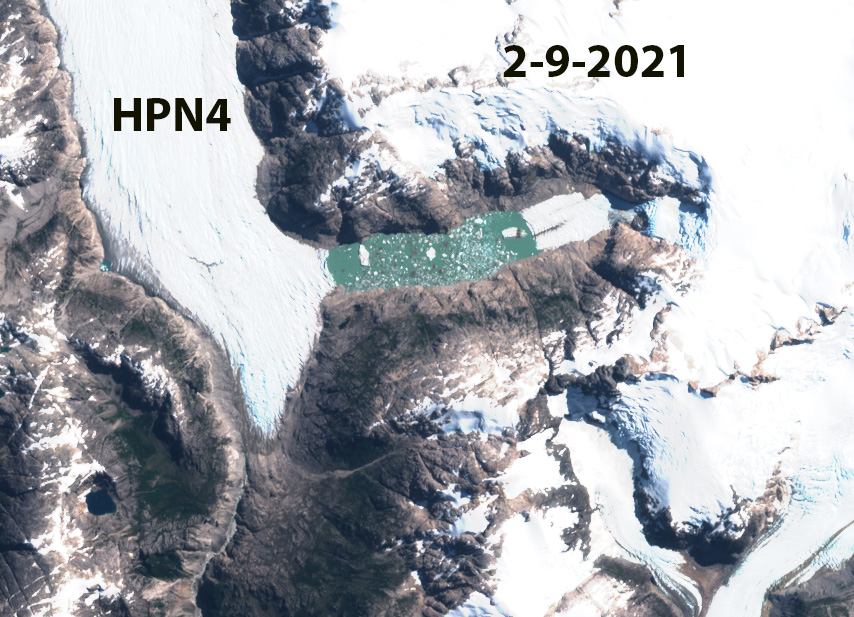

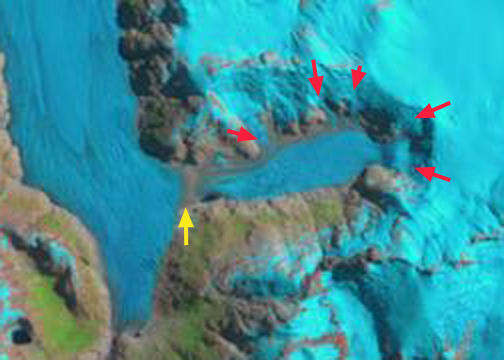

In 1985 the 8 km long RBN and RBS glaciers merged just above the terminus at 820 m, red arrow. In 1985 Inexplorado (RB) was a 7.5 km long glacier terminating at The snowline was at 1300 m. By 2001 RBN and RBS had separated by ~1 km with the formation of a new lake at the former terminus. RBS is developing a nunatak at Point A. Inexplorado had retreated 1 km with a proglacial lake just beginning to develop at the terminus, while the northern tributary at Point B is still feeding the main glacier. By 2016 the retreat of RBN has led to the development of three new alpine lakes in the deglaciated valley. By 2016 RBS thinning and retreat has led to the Point A nunatak in the lower section of RBS becoming a significant bedrock exposure. In 2016 The retreat of Inexplorado has led to the formation of a nearly 0.9 km long proglacial lake and the former northern tributary at Point B has separated. By 2022 RBN has retreated 4.8 km losing 60% of its length since 1985, it has detached from the accumulation and the eastern margin has two lobes now terminating in proglacaial lakes. RBS has retreated 4 km, losing 45% of its length since 1985. Point A is beginning to merge with terminus and the main terminus is likely retreating into a new lake basin. Both RBS and RBN terminate at ~1200 m. Inexplorado has retreated 2.3 km since 1985, 30% of its length, and is still 5.3 km long, terminating at ~1300 m, A new lake basin will likely form between the current terminus and the base of the cefall 1.5 km upglacier of the terminus. The snowline in 2015, 2016 and 2022 was at 1600-1700 m. This leaves only a small percentage of the glacier area above the snowline. The large valley glaciers that just 30 years dominated the headwaters of Rio Blanco have lost ~50% of their length and area and will soon be small slope glaciers clinging to the highest peaks. Retreat here is more extensive than seen 100 km to the northwest at Calbuco Volcano or to the south at the Quelat Glacier Complex.

Rio Blanco Glaciers in Hornopirén Naitonal Park, Chile in Landsat 7 and 8 images from 2001 and 2016. Red arrows indicate 1985 terminus position, yellow arrows 2022 terminus position. Point A is an emerging bedrock nunatak and Point B is where tributary separation has occurred.

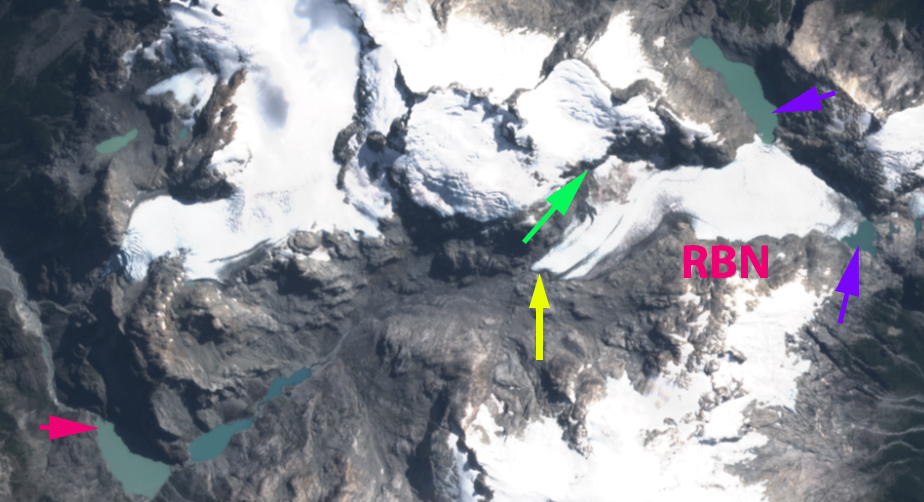

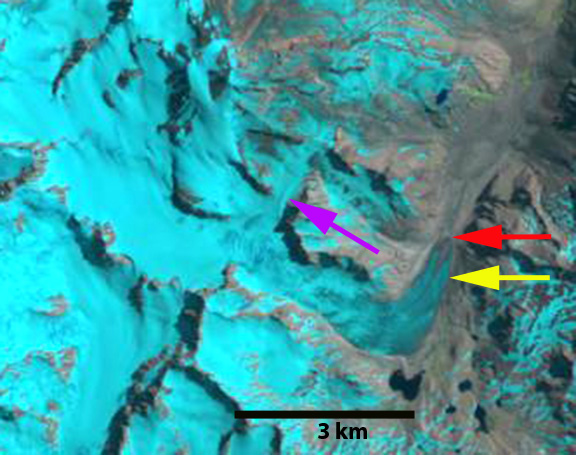

The Rio Blanco North Glacier in March 2022 Sentinel image indicating the two proglacial lakes on eastern margin, purple arrows, the detachment at the green arrow, 1985 terminus locaiton red arrow and 2022 terminus location yellow arrow.