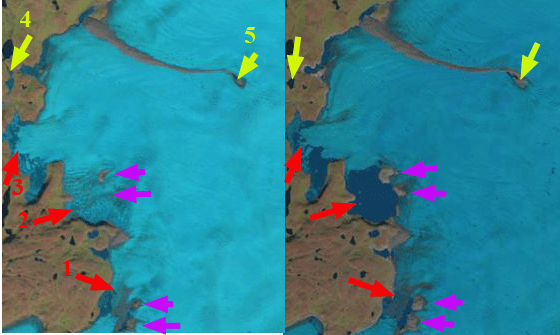

Comparison of 1986 and 2015 Landsat image of Bernardo Glaciers three termini, north, main and south. Red arrows indicate 1986 terminus location and yellow arrows the 2016 terminus location. Indicating the substantial retreat of each terminus and lake expansion for the north and main terminus, while the lake drained at the southern terminus.

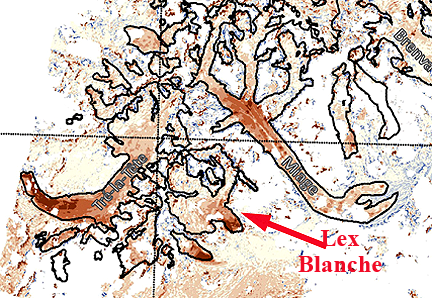

Bernardo Glacier is a difficult to reach outlet glacier on the west side of the Southern Patagonia Icefield (SPI). It The glacier currently ends in an expanding proglacial lake system, with three primary termini. Here we examine changes from 1986 to 2016 using Landsat images. Willis et a (2012) quantify a rapid volume loss of the SPI from 2000-2012 of 20 giga tons per year mainly from rapid retreat of outlet glaciers. They note a thinning rate of 3.4 meters per year during this period of the Bernardo Glacier region. Mouginot and Rignot (2014) illustrate that velocity remains high from the terminus to the accumulation zone on Bernardo Glacier. They also indicate the accumulation zone does not extend as far east toward the crest of the SPI as previously mapped. Davies and Glasser (2012) indicate that over the last century the most rapid retreat was from 2000 to 2011.

In 1986 Bernardo the southern terminus of the glacier was nearly in contact with Tempano Glacier. The main terminus primarily ended on an outwash plain with a small proglacial lake developing. The northern terminus had retreated a short distance south from a peninsula. By 1998 the northern terminus had retreated into a wider, deeper lake basin, filled with icebergs. The main terminus is still mainly grounded on an outwash plain. A small lake has developed between Bernardo Glacier and Tempano Glacier to the south. By 2003 the northern terminus had retreated 2 km from 1986, the main terminus 1.5 km and the southern terminus 1.2 km. By 2015 the lake between Tempano and Bernardo Glacier had drained. The main terminus had retreated 1.5 km since 1986. In 2016 the northern terminus had retreated 3.5 km since 1986, the main terminus 2.5 km and the southern terminus 2.75 km. The largest change is the loss of the lake between Tempano and Bernardo Glacier which slow the retreat of the southern terminus. If this terminus retreat into the another lake basin that shared with the main and north terminus, this would likely destabilize the entire confluence region. The nearly 1 km retreat in a single year from 2015 to 2016 of the main terminus indicates the instability that will lead to further calving enhanced retreat. The retreat of this glacier fits the overall pattern of the SPI outlet glaciers, for example Chico Glacier and Lago Onelli Glaciers

1998 Landsat image. Red arrows indicate 1986 terminus location and yellow arrows the 2016 terminus location.

2003 Landsat image. Red arrows indicate 1986 terminus location and yellow arrows the 2016 terminus location. Main terminus beginning to retreat from outwash plain.

2015 Landsat image. Red arrows indicate 1986 terminus location and yellow arrows the 2016 terminus location. Note the considerable difference in main terminus versus one year later in 2016.