Heat waves and glaciers don’t usually go together; however, in the last several years an increasing number of heat waves have affected alpine glacier regions around the world. This is true from Arctic Canada to the Himalayas from the Andes to Alaska. Here we review a number of these heat waves from 2018-2022, that I have been involved with assessing and observing. In particular heat waves leave a greater portion of the glacier snow free, which enhances melting and mass balance losses. This is most pronounced when the heat wave occurs prior to or early in the melt season exposing bare glacier ice for the bulk of the melt season. This occurred in summer 2021 in the Pacific Northwest, in summer 2022 in the Central Andes of Chile and Peru, and during the pre-monsoon season in 2022 in the Himalaya. In the summer of 2022 heat waves impacted the glaciers of Svalbard and Europe. In the summer of 2023 the Central Andean glaciers have again been stripped of snowcover.

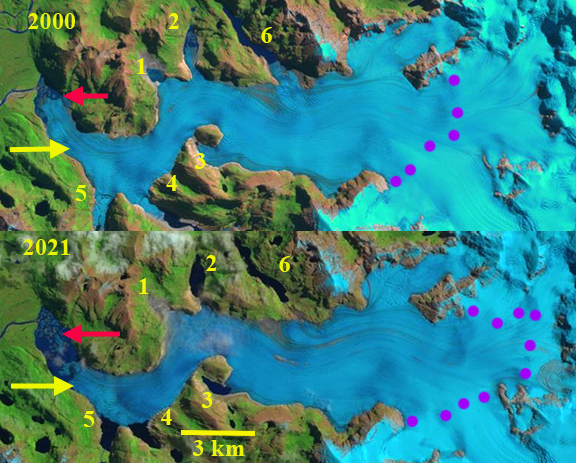

Lowell Glacier in Landsat images from 7/4, 7/26 and 8/11 with Sentinel images from 7/22 . The snowline is shown with purple dots. Point A-F are fixed reference locations. The snowline migrated upglacier 20 km and 300 m in elevation. A significant snow swamp is between the yellow and purple dots on 7/26, that was not present on 7/22.

The beginning of this “wave” of observations of heat wave impacts on glaciers, was on Lowell Glacier, Yukon where a large snow swamp formed in a matter of days during a Yukon/Northwest Territories Heat Wave. On July 26, the slush covered an area of more than 40 square kilometers, with the rapid development of such a large melt area on Lowell Glacier coinciding with four days where daily temperatures at nearby Haines Junction (~60 km northeast of the glacier) reached 29 degrees Celsius. The only way to generate an extensive snow swamp is to have the snow saturated with water all the way to the surface NASA’s Earth Observatory (NASA EO).

Taku Glacier transient snowline (purple dots) in Landsat images from 7/21 and 9/16/2018.

This same heat event led to the observation that the snow lines on Taku Glacier in Alaska were the highest they had been since tracking began in 1946, 200 m higher than previously observed, with the snow line rising +10 m/day during the heat wave (Pelto, 2019).

Fork Beard (F) and Nerutusoq Glacier (N) Baffin Island on June 1, 2019, June 18, 2019 Sentinel images and June 30 Landsat image. Purple dots indicate the snowline.

During June 2019 on Baffin island Pangnirtung featured four days with record temperatures for that date June 5 (15.1), June 11 (13.5) and June 12 (13.6), and June 19 (14.4). There were 14 days with a maximum temperature above 10 C. On Fork Beard Glacier and Nerutusoq Glacier this drove a snowline rise from 800 m on June 1 to 1100 m by June 18 and 1150 m on June 30. A rate of over 10 m/day for the month.

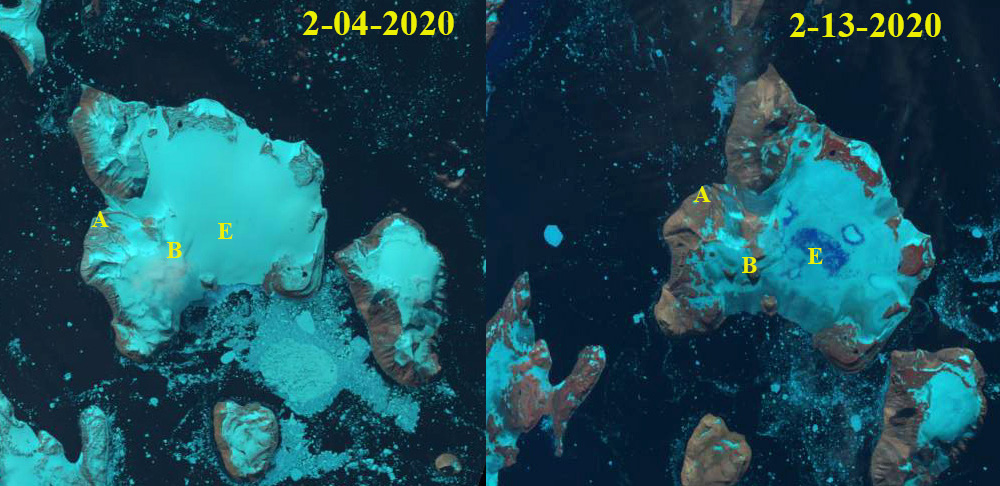

Eagle Island Ice Cap, Antarctica in Landsat images from Feb. 4, 2020 and Feb. 13, 2020. Point E indicates an are area of snow/firn that is saturated with

An all-time temperature record for Antarctica in February 2020, a high-pressure ridge and a blocking high in the Drake Passage caused anticyclonic circulation bringing warm moist air from the Pacific Ocean to the Antarctic Peninsula Xu et al (2021). This led to vertical air flows in a foehn warming event dominated by sensible heat and radiation made generating abrupt warming Xu et al (2021). The visible impact of this heat event were the rapid rapid formation of melt ponds on Eagle Island Ice Cap I reported to NASA EO. On Eagle Island Ice Cap melt averaged 22 mm/day from Feb. 6-11 based on MAR climate model output forced by the Global Forecast System (GFS) generated by Xavier Fettweis. Rapid melting generating significant snowline rise on Coley Galcier, James Ross Island as well (Pelto, 2020).

Nanpa La (NPL) and Nup La (NL) in October 13, 2020 and January 17, 2021 Landsat imagery indicating the snow line rise that has persisted into mid- winter. Snow line indicated by yellow dots.

When record warmth spread over the Mount Everest region in January 2021, the snow lines near Mount Everest rose durng the October-December 2020 period, and remained at nearly 6,000 meters, including the key glacier passes from Nepal into China being snow free into late January. The National Geographic Perpetual Planet Expedition weather team, led by L. Baker Perry and Tom Matthew, had installed weathers stations at high elevations on Mount Everest in 2019 (Matthews et al 2020). These stations provided field observation of how warm it was during this period, which explained the snow free glaciers in winter. Temperature observations and reconstructions of daily weather conditions, dating back to 1950, indicated that the region had experienced the five warmest winter days since 1950 during a short period in January 2021. Prajjwal Panday examined the decline of snow cover area and rise of sthe snowline on glaciers from Oct. 2020 -January 2021 finding a 15% depleation and 200 m rise respectively. Even in the highest mountain range in the world, we are seeing melt conditions during the winter. This study was first published by NASA EO within a month of the event, and then in the journal Remote Sensing.

Easton Glacier has limited snowpack with two months left in the melt season in 2021. Dots indicate the firn line.

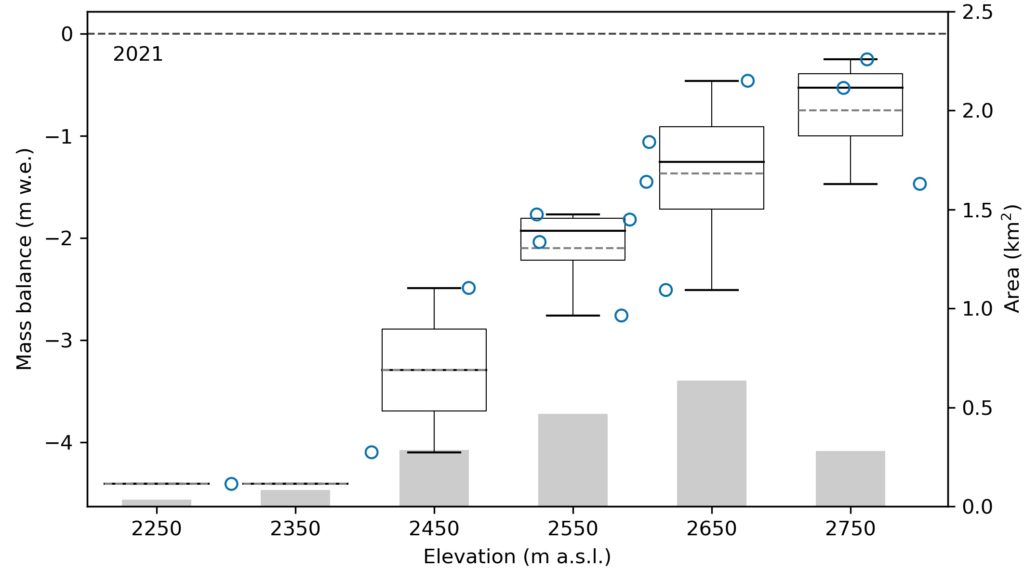

The next warm weather event was the Pacific Northwest record heat in late June 2021, setting all-time records across the region. Thompson et al (2022). comparison of daily summer maximum temperaturesthat were 3.6 SDs from the mean.. This heat wave quickly melted away much of the winter snowpack on many glaciers. The heat wave and ensuing warmth stripped the snowcover from glaciers right to the summit on the highest mountains from Mount Shasta, California to Mount Baker, Washington by mid- August exposing the dirtier ice that lies underneath the snow and melts more rapidly than snow under the same weather conditions, to the summit of these mountains. The led to increased discharge in glacier fed streams, while non-glacier fed streams in the region had significant declines in discharge. For the Nooksack River heat waves generate a 24% increase in discharge in the glaciated North Fork and a 20% decline in the unglaciated South Fork (Pelto et al 2022). For water temperature the mean increase was 0.7 °C (±0.4 °C) in the North Fork and 2.1 °C (±1.2 °C) in the South Fork (Pelto et al 2022). The resulting volume loss during the summer season has been the highest we have observed in our 38 years of monitoring North Cascade glaciers. We observed stunted alpine plant growth, experienced days of smoky air limiting visibility and had to navigate and measure more open crevasses than usual.

Whitney Glacier on Mount Shasta in 2021 Sentinel Images.

Jackson and Blackfoot Glacier in early September Sentinel 2 false color images. Point A indicates exposed ice showing annual layers. Point B indicates exposed firn that had been retained through previous summers. The gray color of the firn indicates how dirty it is and that its albedo would enhance melting.

Mount Shasta in California fared even worse, losing all snow cover on its glaciers by September 6. The largest glacier on the mountain and in California, Whitney Glacier, began to separate. In all, the glaciers there had lost 50 percent of their area and volume this century, including ~10-15 percent this summer, and had fragmented from 6 into 17 glacier pieces (Patel, Washington Post, 2021).

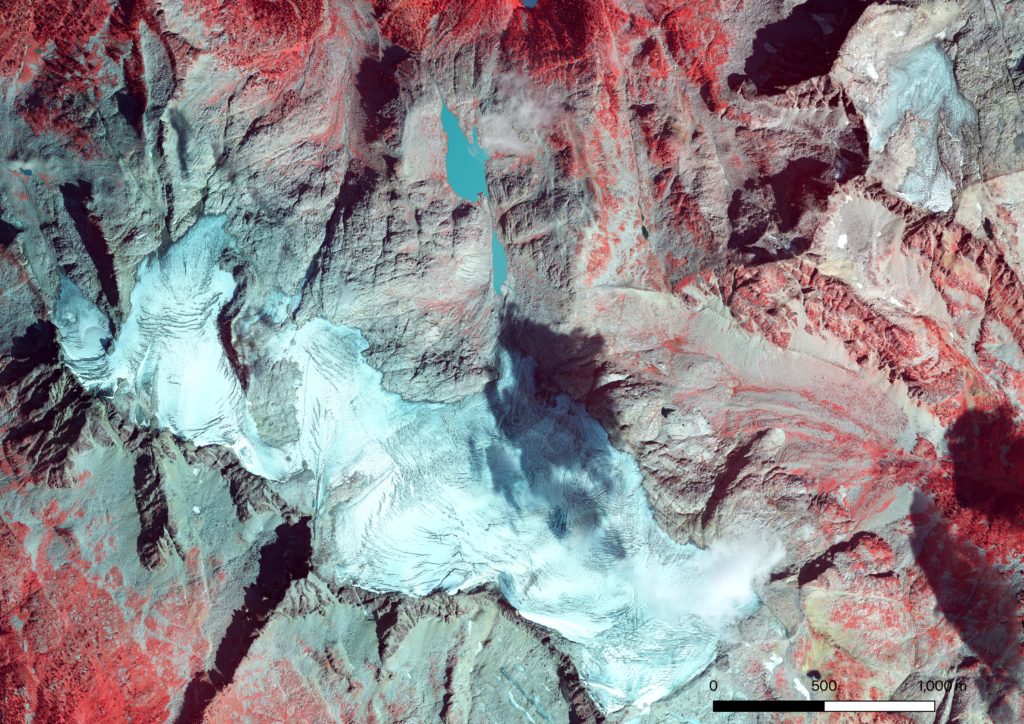

The summer of 2022 in the Central Andes of Argentina and Chile glaciers experience a near total loss of snowpack in January due to early summer warmth, leading to dirty/dark glaciers. The darker surfaces of the glacier melt faster leading to more rapid area and volume loss. This includes fragmentation and rapid expansion of bedrock areas amidst the glacier. The snow free conditions lasted until the end of March, extending the impact from the January observations emphasizing that this was a regional issue this summer with snowpack lost from Bajo del Plomo Glacier, Cortaderal Glacier, Palomo Glacier, Volcan Overo Glaciers, Volcan San Jose Glaciers , Cobre Glacier and Olivares Beta and Gamma Glaciers across the Central Andes of Chile and Argentina.

Volcan San Jose glaciers in Feb. 17, 2022 Sentinel image. This highlights just how dirty the ice surface is and how limited the retained snowcover is.

Cobre Glacier, Argentina in false color Sentinel 2 images from Jnauary 13, 2022 and March 16, 2022. Note the expansion of bedrock area amidst the glacier at Point A, glacier fragmenting at Point B and Point C.

Volcan Overo in Sentinel image continues to fragment with no retained snowcover this summer, and bedrock expansion at Point A.

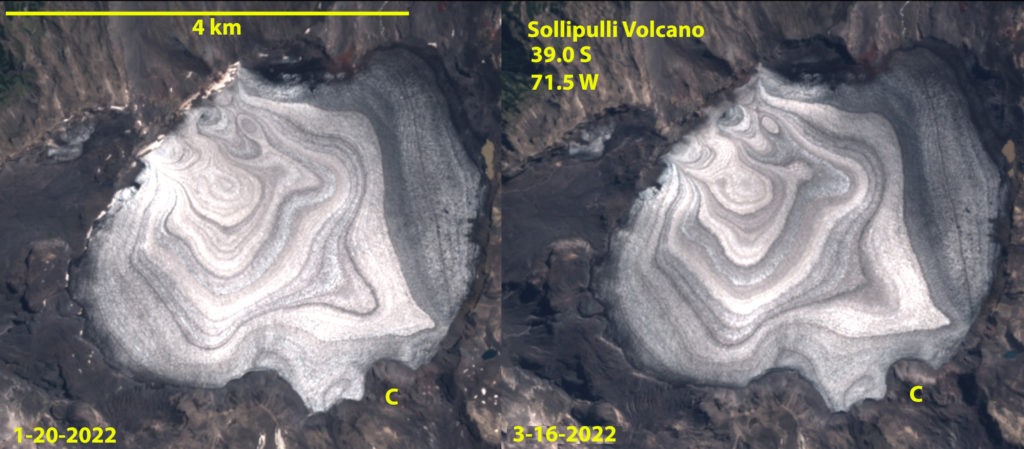

Sentinel images the loss of all snowcover on Sollipulli Glacier that continued from January until at least March 13 2022. Note the annual layers preserved in the glacier ice now exposed at the surface.

Langjokulen (La), Kvitisen (Kv), Bergfonna (Be) and Blaisen (Bl) ice caps on Edgeøya in Sentinel image from 8-20-2022 illustrating the lack of snowcover, limited firn areas and numerous annual layers. This pattern of annual layers due to glaciers being stripped of snow cover is becoming increasingly frequent. Note Andes last winter and Pacific Northwest summer 2021.

During the summer of 2022 Svalbard experienced an extended heat wave in August that led to loss of snowpack on a number of ice caps on Edgeoya.

Rapid snowcover loss on Rhone Glacier early in summer of 2022 in Sentinel images

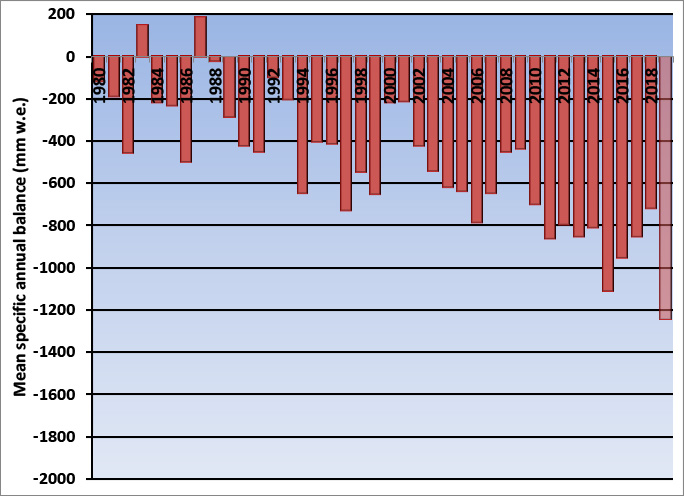

The European Alps were hard hit in the summer of 2022 experiencing their most negative balances observed during the 70 years of observations.

In the summer of 2023 central Andean glaciers lost snowcover during the February heat waves.

Volcan Overo, Argentina with expanding lakes, blue arrows and fragmenting at yellow arrows.

Sollipulli Glacier lost snowcover in February 2023

The bottom line is that glaciers are simply not compatible with recurring heat waves and the intensity and frequency of these is increasing. This is true from Arctic Canada to the Himalayas from the Andes to Antarctica. This year, for the 34th consecutive year, Alpine glacier volume in the world will decline; their business model is not sustainable with our climate.

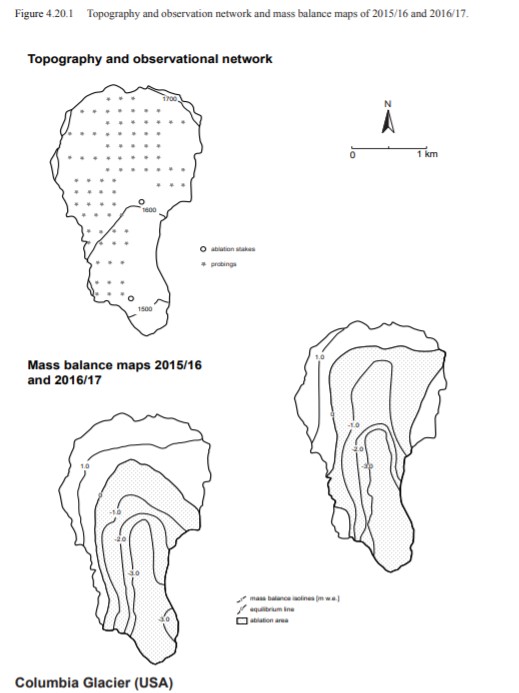

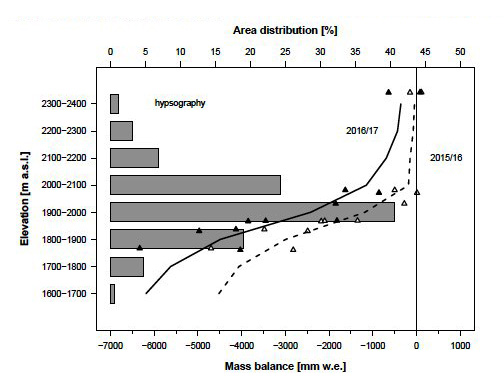

Topographic map of Mt. Shasta.indicating the top of Whitney Glacier near the summit of Shasta and the ~1981 and 2005 terminus position.

Topographic map of Mt. Shasta.indicating the top of Whitney Glacier near the summit of Shasta and the ~1981 and 2005 terminus position.