Guest Post by Clara Deck

Instagram: @scienceisntsoscary

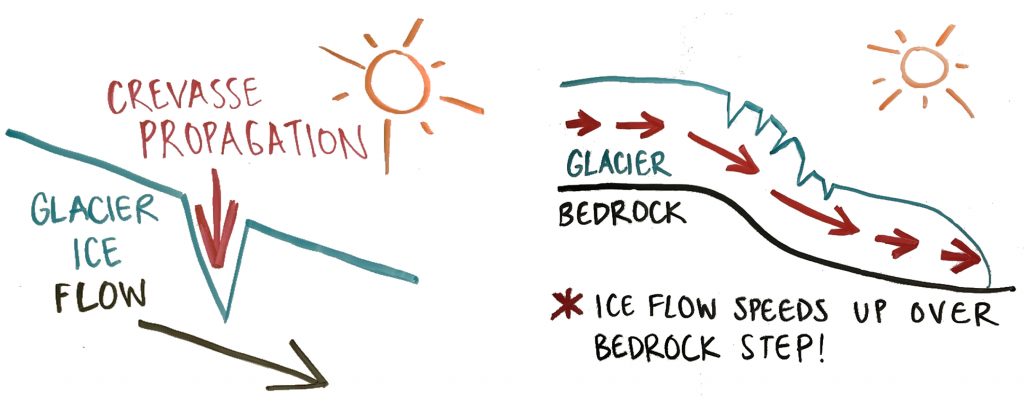

Crevasses on mountain glaciers are large cracks in the ice which often propagate from the surface downward. The initial break will happen when stress exceeds the inherent ice material strength. This article will focus on surface crevasses, though this basic physical understanding also applies to basal crevasses or large-scale rifts in ice sheet and shelf settings.

In mountain glacier systems, crevassing is likely to occur as ice flows over bedrock “steps.” Imagine you are baking a pie, and it is time to mold your pie crust to the pan. You must be very careful when bending the dough around the pie pan, because it may crack if you fold it too much or too suddenly.

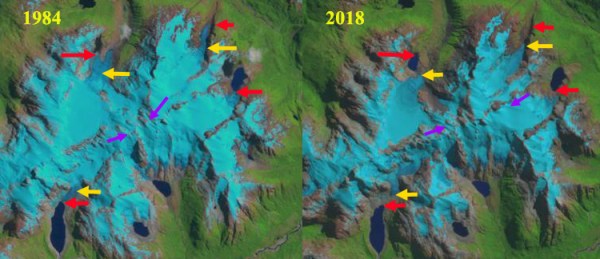

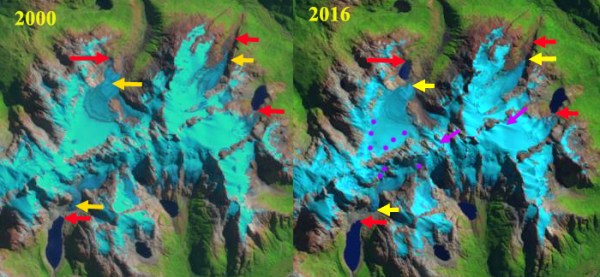

Glaciers are the same way, and so another driver for crevasse formation is ice flow speed up in these areas. Other factors that could be at play are roughness of the underlying bed or drag along valley walls. The above photo of Rainbow Glacier shows a complex surface of crevassed and smooth areas, which hints to a similarly complex underlying bed.

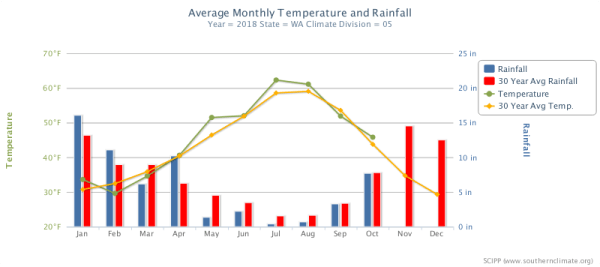

During the 2019 field season of the North Cascades Glacier Climate Project, we measured these crevasses in a few different ways. Seven field seasons ago, Jill Pelto began collecting data on crevasse depth. She uses a cam line, which is essentially a weighted tape measure, to determine total crevasse depth on each glacier. This photo shows Jill measuring a crevasse on Easton Glacier. She tries to analyze crevasses in similar regions of the glaciers from year to year to achieve a cohesive dataset which could be useful on a long-time scale. This data has the potential to shed light on important glacial changes and how they may relate to regional warming or shifts in precipitation patterns in the North Cascades. The data could also illuminate differences in the behavior of each individual glacier. Overall the number of crevasses has declined, in 2019 average depth on Easton Glacier was 10-15 m.

Another technique we used in the field is crevasse stratigraphy. Upon looking inside open vertically-walled crevasses in the accumulation zone, there are clear layers exposed on the crevasse walls. The layers are the remaining snow from each accumulation season, with the most recent winter’s snow on top. Using a rope marked at each decimeter, we work together to measure the depth of each exposed snow layer. These measurements give a pinpointed measurement of mass balance, and thus glacial health, throughout the past couple of years.

In some open crevasse features, you can see that many more years of stratigraphy are preserved, like in this photo on Easton Glacier. Each visible layer is from a year during which the amount of snowfall exceeded the summer melt, and there is no remaining evidence from years with higher melt than snow accumulation.

Other information we can gather from crevasses is related to the internal stresses in the ice. Crevasses are opened by pull-apart forces which act perpendicular to the trend of the crevasse.

If you are able to relate the crevasse orientations to the stress within the glacier, it is useful in evaluating the dominant stresses and how they change throughout the glacier spatially. Identifying the locations of crevasse groupings is also a valuable observation, as it reveals the areas with high stress, and may give clues as to where bedrock steps exist below the glacier.

Crevasses are often perceived as scary and have a negative connotation, and while they are hazardous to glacial travelers (always be VERY careful and have the correct gear when navigating crevasses), they are actually a sign of glacial productivity. A healthy glacier’s crevasses are frequent and deep, because thick, flowing ice generates high stress conditions.

The North Cascades Glacier Climate Project has observed glacial thinning due to lower rates of snowfall paired with more intense summer melt seasons over the past 36 years. This has led to a reduction in the number of crevasses in many areas. During summer 2019, the glaciers we visited in the North Cascades will lose up to 2 meters of snow from their surfaces to melting. It is likely that as this pattern continues, there will be even less surface crevassing on the glaciers.

Figure 2. January 1st snow survey data from the

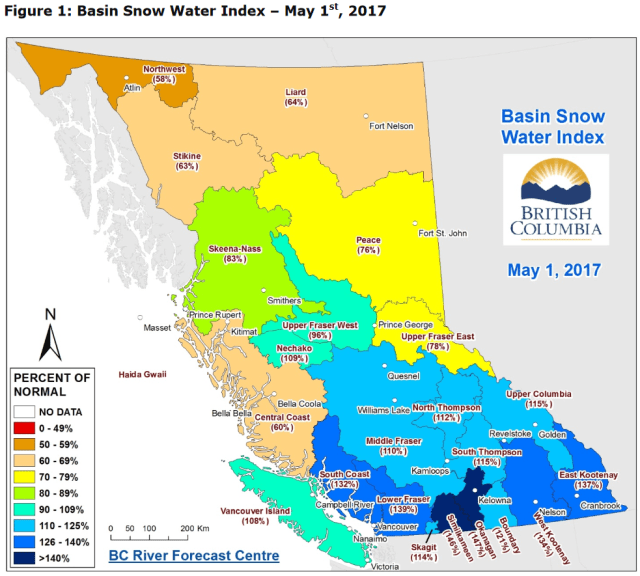

Figure 2. January 1st snow survey data from the  Figure 3. May 1st snow survey data from the

Figure 3. May 1st snow survey data from the