Columbia Glacier in 2015 viewed from the ridge above the glacier. The firn line is marked by blue dots. The age of the snow surface of 2015 and the firn surfaces of 2011-2014 are noted.

For an alpine glacier to be in equilibrium at the end of summer the glacier needs to be 50-70% covered in snow from the previous winter. This is the accumulation area ratio (AAR). AAR is a good measure of mass balance, which is why AAR is reported for WGMS reference glaciers. In recent years we have seen periodic strongly negative balance years that have removed all or nearly all of the snowpack from a glacier leaving an AAR of less than 10%, and considerable exposed firn. This typically occurs in assocation with a year that feature prolonged dry warm conditions in winter that limit snow accumulation or even reduce it, and/or summers with heat waves and extended warm periods that melt away the snowpack rapidly, particularly early in the melt season. This leads to exposure of firn, which is the snowpack retained from previous winters, hence more than a year old, but not yet glacier ice and significantly dirtier/darker than snow from the most recent winter. This firn melts more rapidly than snow, largely because it is darker. This leads to additional mass loss for the glacier. By the end of summer in strongly negative years we can see where the firn area boundary with glacier ice. This marks the region below which no accumlation has been retained in recent years, hence older ice is exposed. As such it delineates the multi-year accumulation area, the effective accumulation zone of the glacier. This would not be accuately determined from an simple average of annual AAR values. It is also readily visible in aerial or satellite imagery.

This scenario played out both in the Pacific Northwest in summer 2021 and in the Central Andes summer 2022. Pelto et al (2022) examine the impact of the heat waves on glacier runoff specifically. In New Zealand the 2022 NIWA annual snowline survey also indicate exposed firn below the annual snowline.

The blue dotted line on Columbia Glacier marks the accumulaiton zone for the 2011-2015 period, below that line no snow or firn was retained during that five year period. The is was a year of exceptional mass balance loss in the North Cascade Range (Pelto, 2018). Below is an example from Sholes Glacier in 2014 indicating the snow line in August and again in September now with a separte firn line apparent. Note the difference between the snowline for 2014 and the firn line for the 2011-2013 period. Below that point no firn has been retained.

Sholes Glacier snowline and firn line in August and September of 2014.

High negative balance years exposing significant firn areas at he surface have played out with increasing frequency in glaciated mountain regions from the North Cascade Range north through British Columbia to Alaska and across continents to the Alps, Canadian Arctic, Himalaya, and Andes. Glaciers where much of their snow cover is lost by mid-summer, then have the darker firn and ice exposed for enhanced ablation for the rest of the summer. There is no sunscreen they can apply for protection.

For Blackfoot and Jackson Glacier in Glacier National Park, Montana just one small area of snow remained on Blackfoot Glacier in early September of 2021. The area of firn on both glaciers is extensive nearly 50% of the glacier indicating overall an accumulation area of significant size. For Adams Glacier in late summer 2021 there is ~10% snowcover (A), while firn cover is 40% at the end of August.

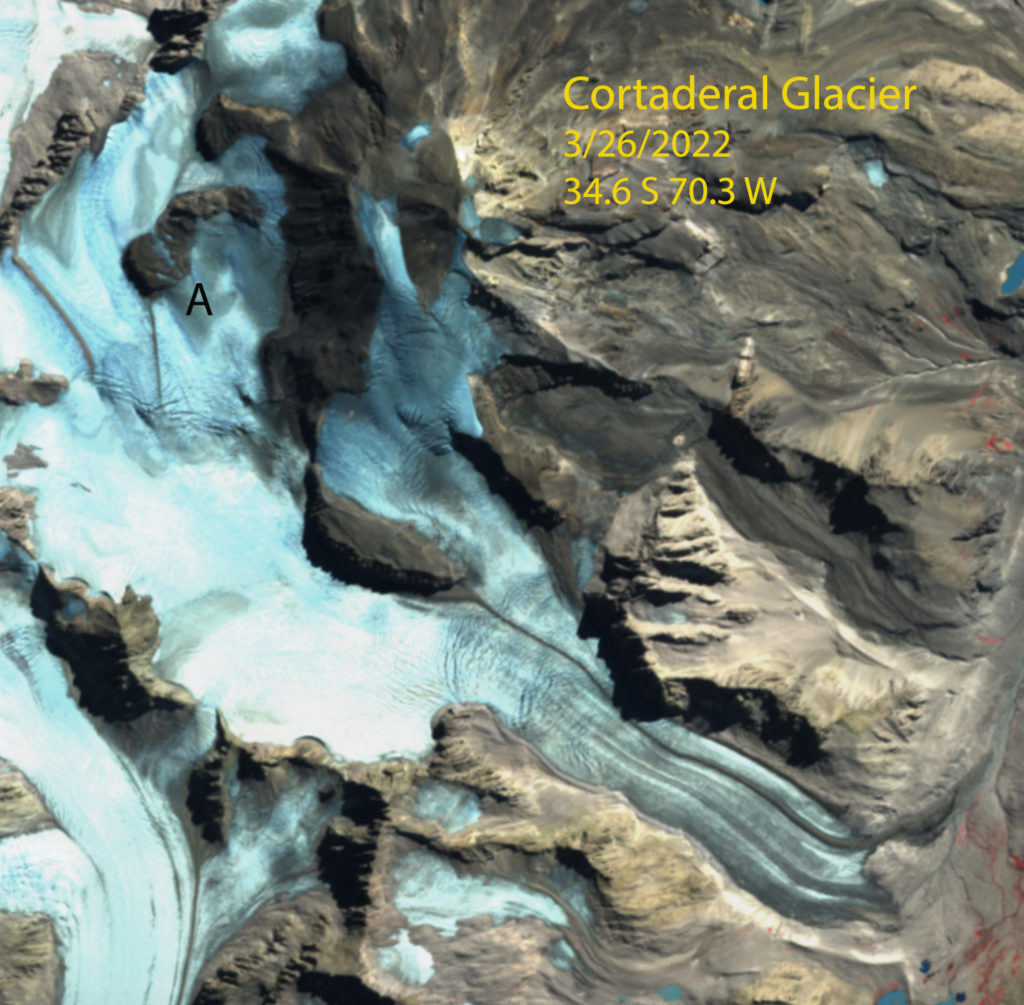

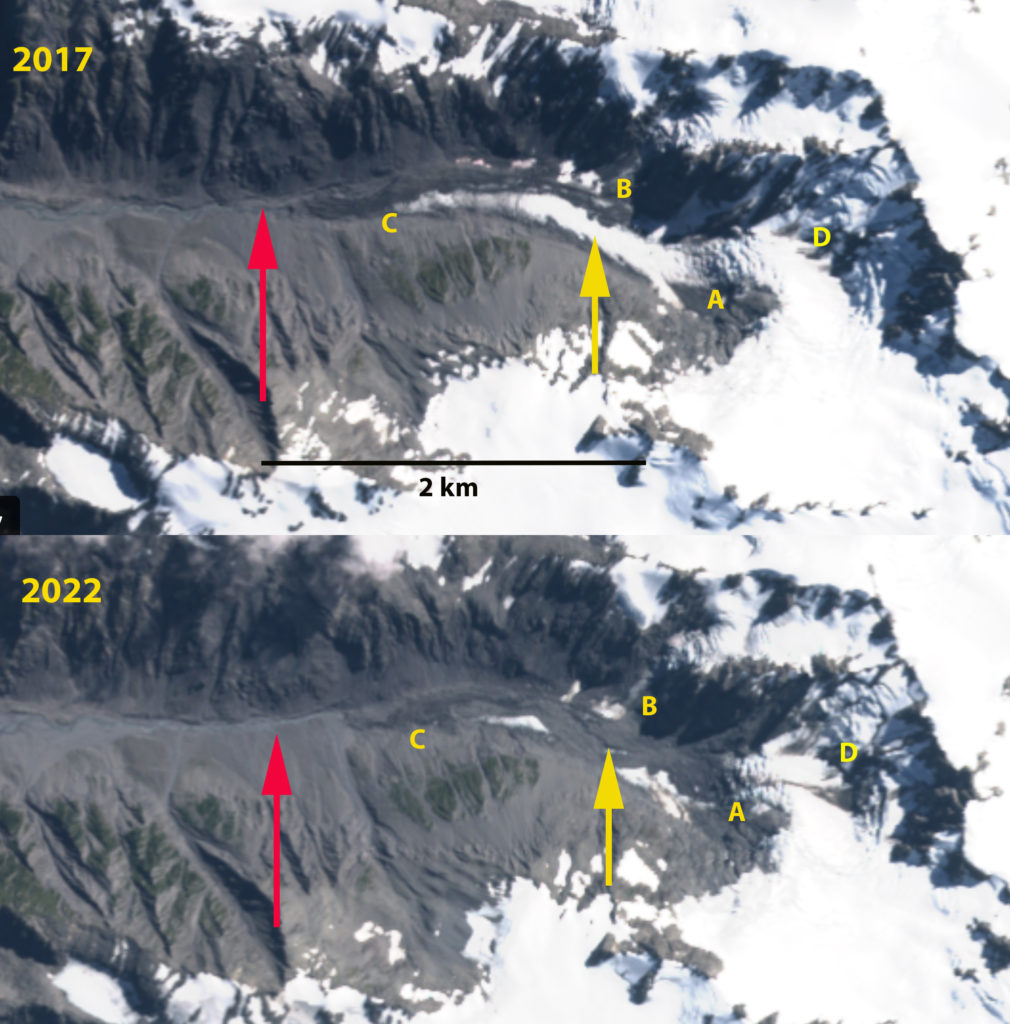

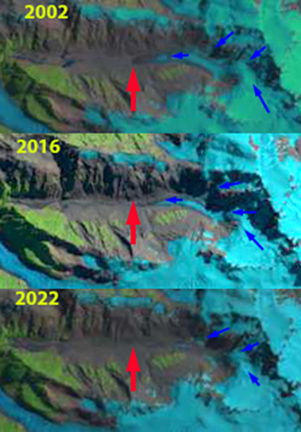

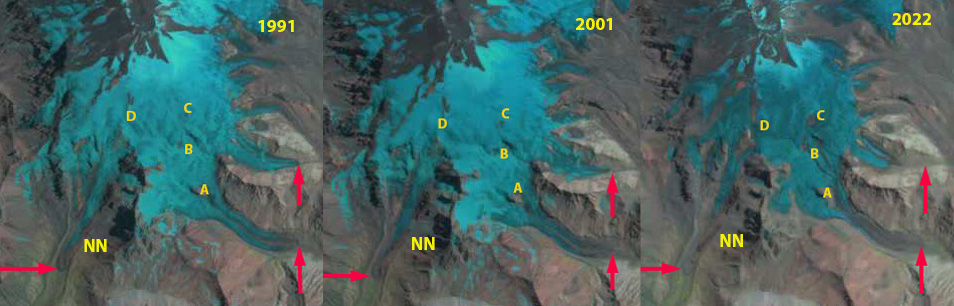

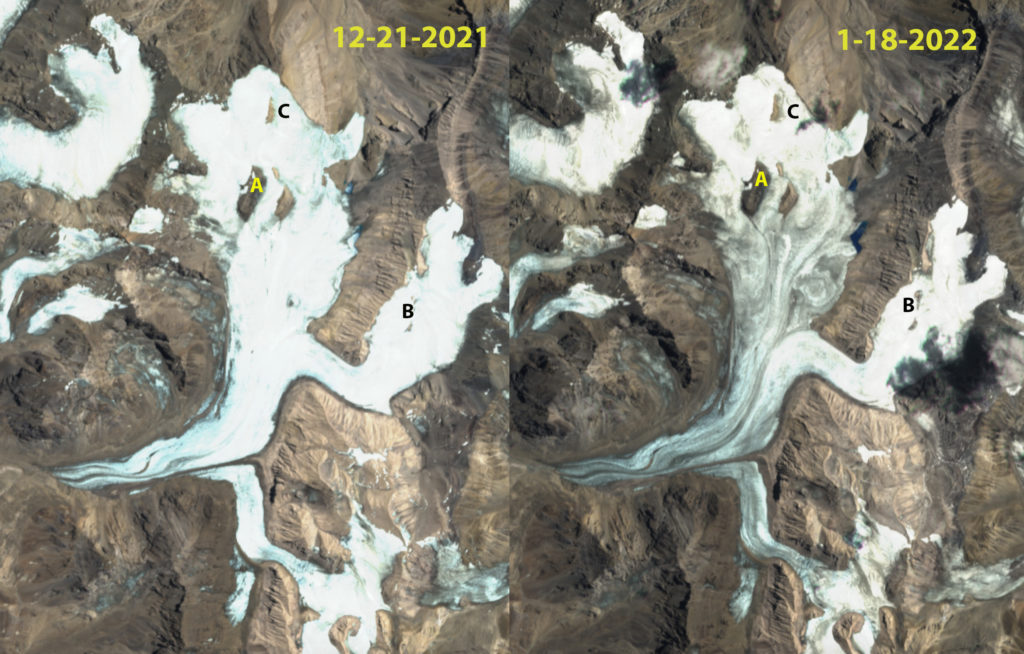

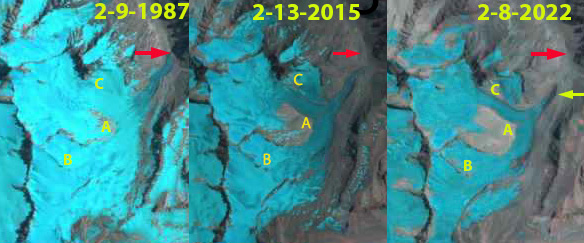

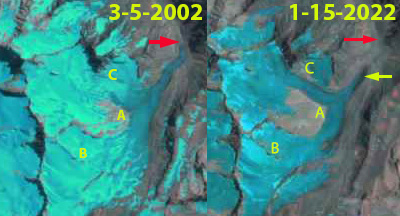

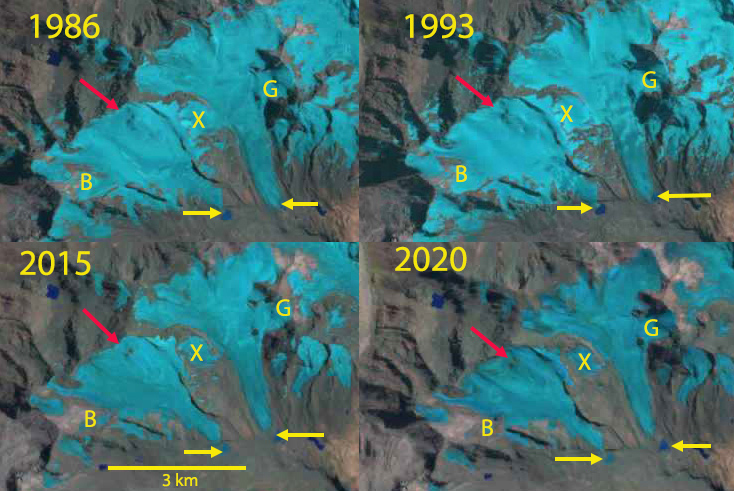

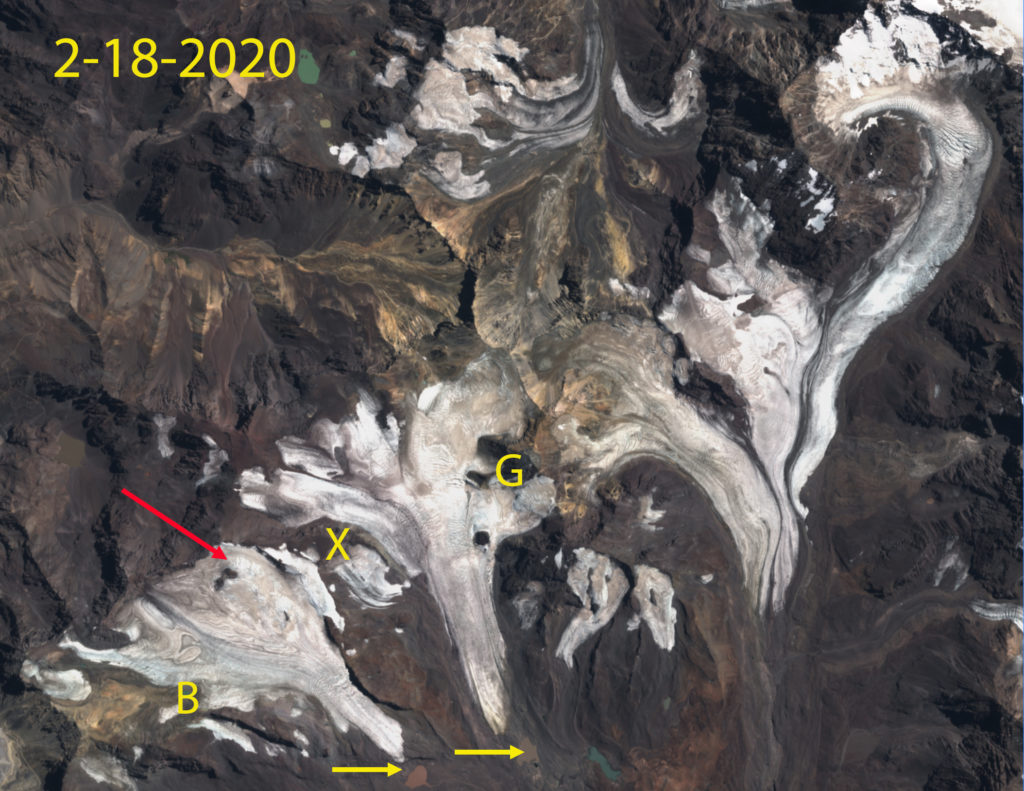

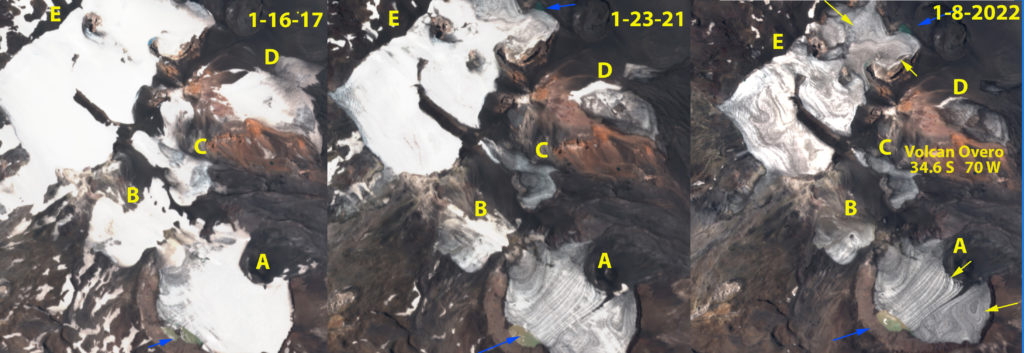

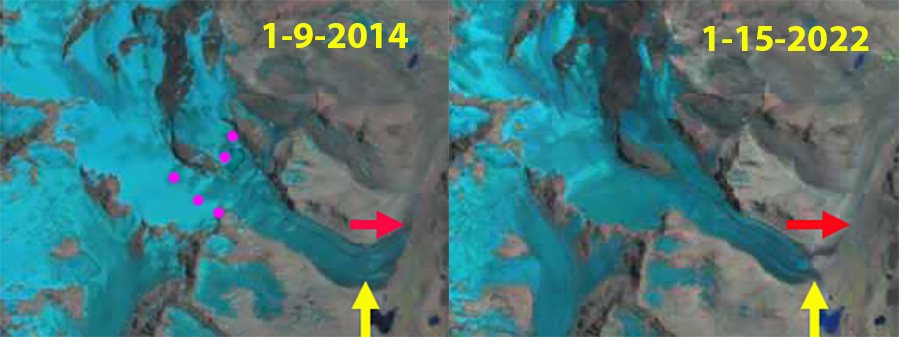

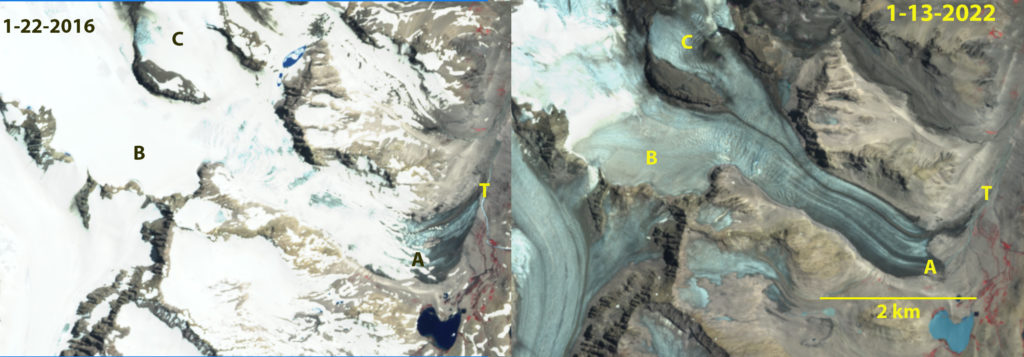

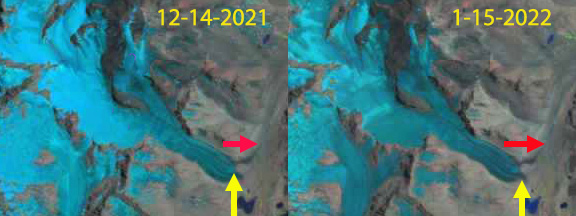

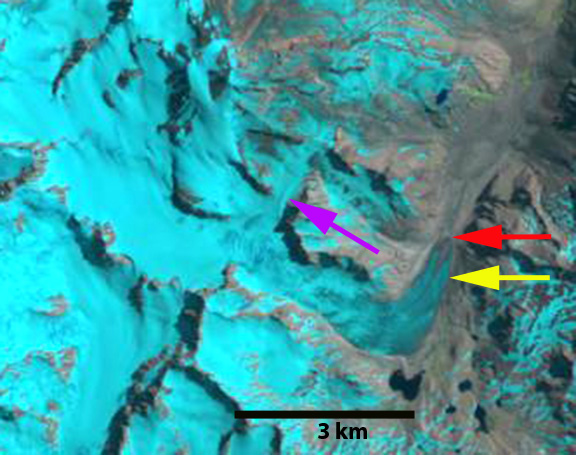

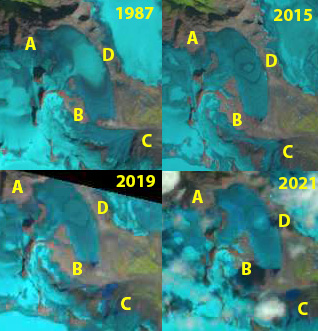

In January 2022 the Central Andes of Argentina and Chile have experienced nearly complete snowcover loss on many glaciers. Volcan Overo, Argentina has four ice masses A-D with limited firn or remaining snowpack. Ice mass E has limited snowcover, but reasonable firn cover extent, not blue dots between firn and bare ice. On Olivares Beta and Gamma Glacier, Chile almost no snowcover remains from Winter 2021, the firn line is limited to the upper portion of both glaciers. This indicates less than 30% of the glacier is an accumulation zone during recent years. There is still six weeks left in the melt season to further reduce this area. The bare surfaces lasted from mid-January into late March leading to extensive mass loss.

For each of the glaciers illustrated here the firn area can be delineated accurately due to the glacier having a significant mass balance loss. The age of the firn cannot be determined without specific knowledge of the glacier or area, but for temperate alpine glaciers firn typically is converted to ice is 5-7 year

The snow cover (S) reamining on Jackston and Blackfoot Glacier in a Sentinel image by early September of 2021 is minimal. The firn area (F) in gray is more extensive.

Adams Glacier with areas of acccumulation (A) and firn (F) in a Sentinel image from Aug. 30, 2021. Green dots indicate the glacier boundary.

Olivares Beta and Gamma Glacier in Sentinel image, with ~10% snowcover remaining and 30% firn cover (blue dots) on January 20, 2022.

Olivares Beta and Gamma Glacier in Sentinel image indicating days of exposure at surface of firn and ice , March 26, 2022.

Volcan Overo, Argentina in January 13, 2022 Sentinel image, with negligible snowcover remaining in mid-summer and firn cover remaining on 30% of the Glacier E.

Volcan Overo in Sentinel image indicating days of exposure at surface of firn and ice , March 26, 2022.

Honeycomb Glacier (H) with evident firn lines below the annual snowline on Oct. 19, 2022 in a Sentinel image.