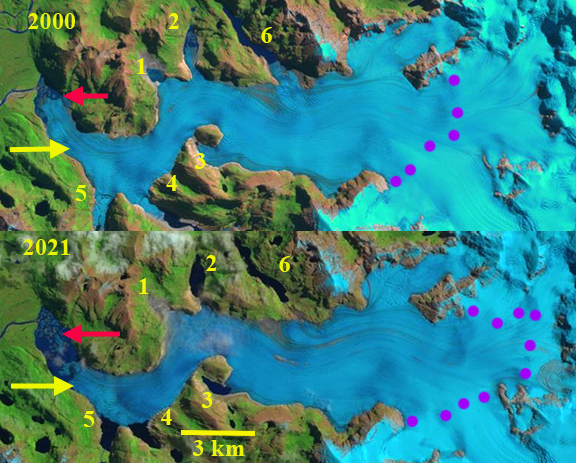

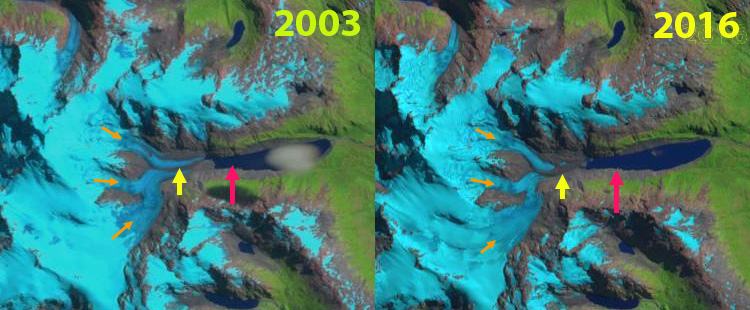

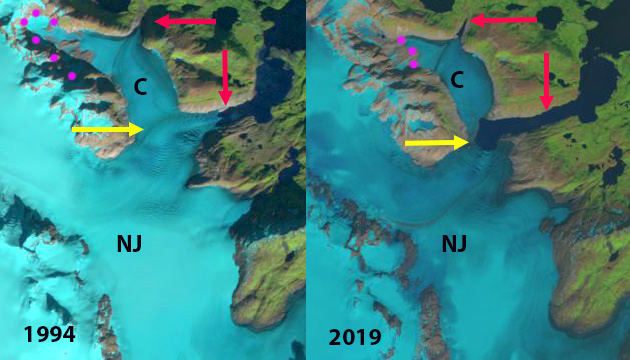

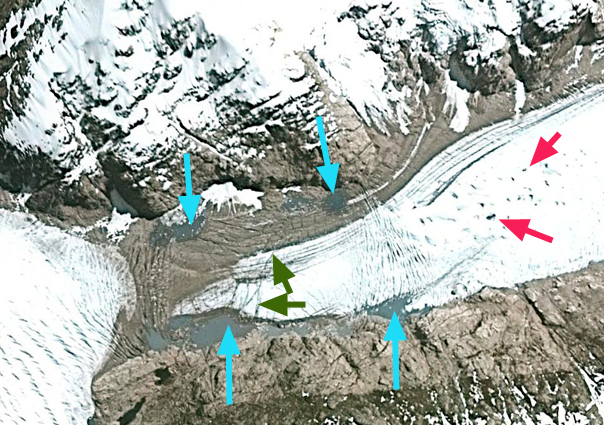

Benito Glacier in 2000 and 2021 Landsat images. Locations 1-6 are current or former distributary terminus locations. Red arrow is the 2000 terminus location and yellow arrow the 2021 terminus location. A small cloud is obscuring an iceberg near terminus. Purple dots are the snowline.

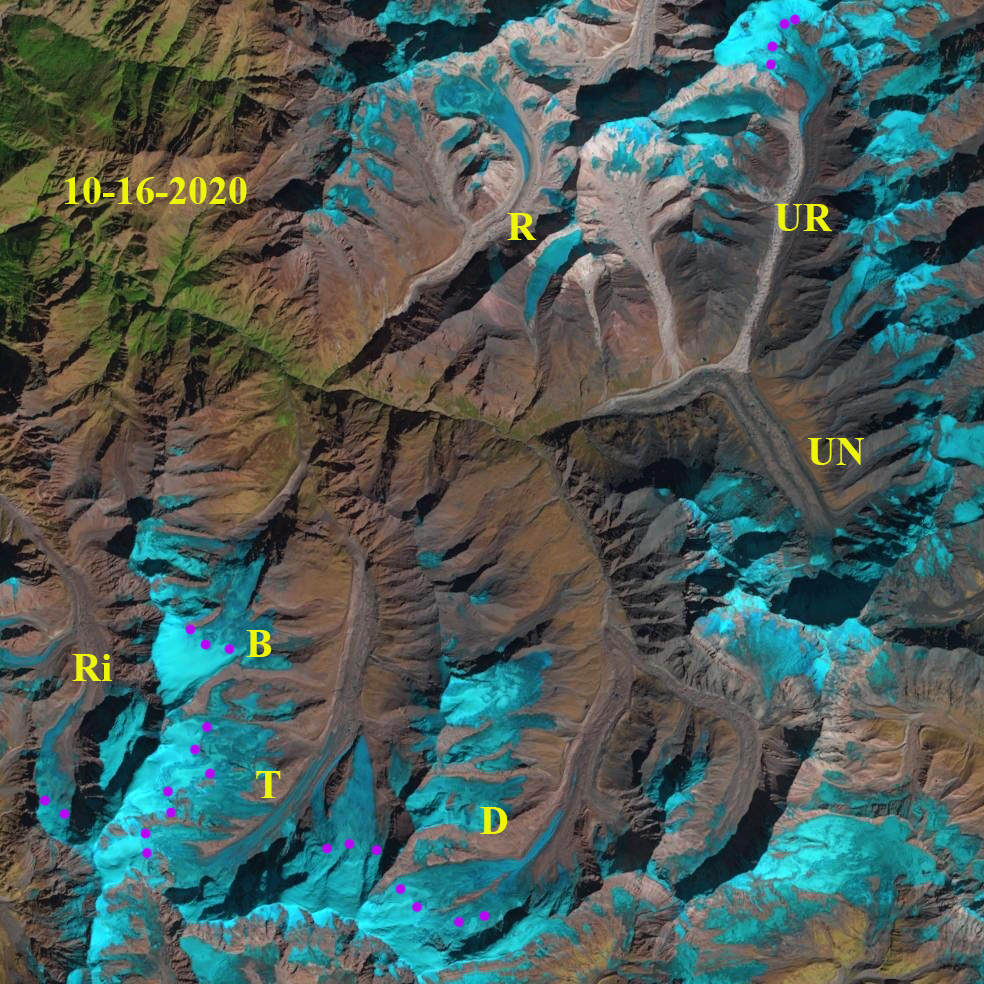

Benito Glacier is a temperate outlet glacier on the west side of the North Patagonian Icefield terminating in an expanding lake. The glacier is south of San Quintin Glacier and north of Acodado Glacier. Loriaux and Casassa (2013) examined the expansion of lakes of the Northern Patagonia Ice Cap. From 1945 to 2011 lake area expanded 65%, 66 square kilometers. Ryan et al (2018) identified thinning of 2.8 m/year in the ablation zone from 2000-2013, and that thinning of over 120 m extended from the terminus to ~750 m from 1973-2017. Mouginot and Rignot (2015) indicate that the velocity of Benito Glacier is between 200-500 m per year along the center line below the snowline. Glasser et al (2016) note the glacier has limited debris cover and that the average transient snowline in 2013-2016 is at 1000 m, substantially above the ~900 m average from earlier.

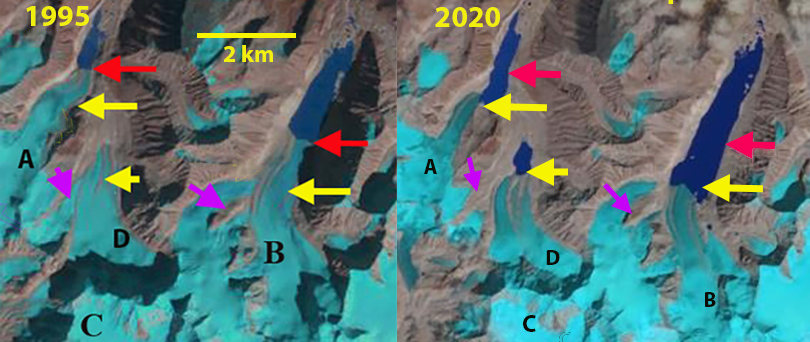

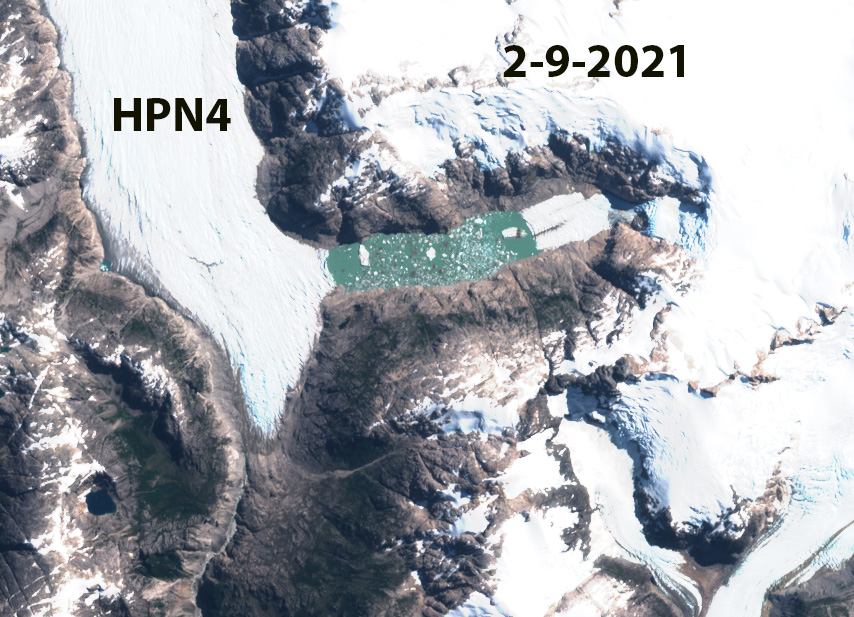

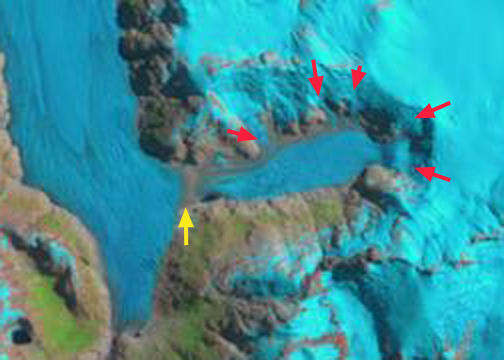

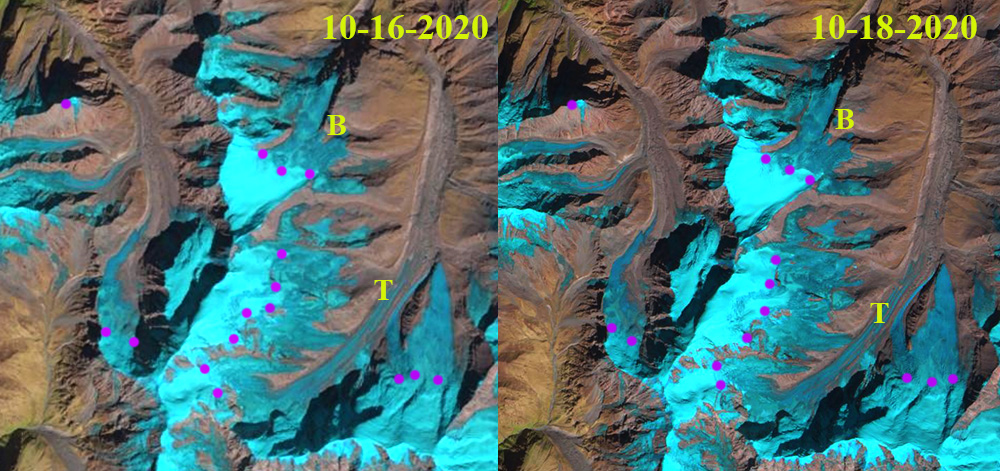

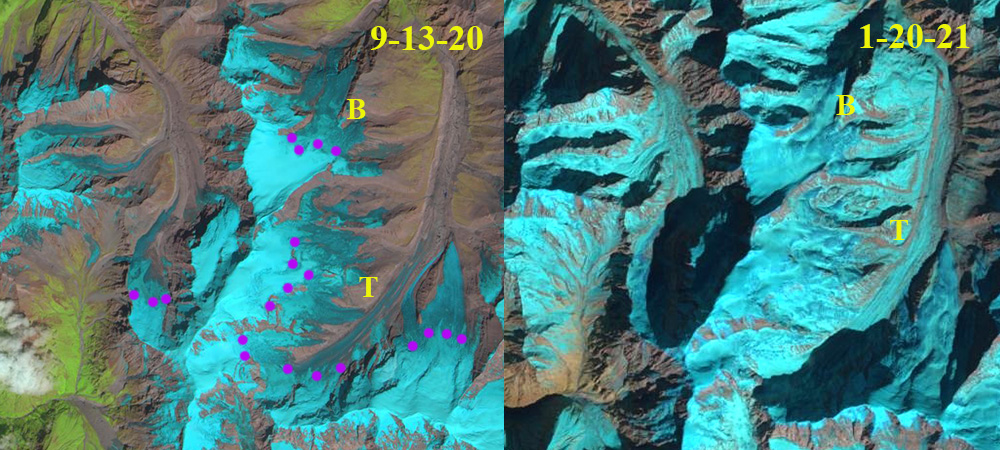

Benito Glacier in 1987 main terminus was on an outwash plain. The glacier has five distributary termini (1,2,34,5,6) two of which had open proglacial lakes in 1987. At Point 3 the glacier flows around a nunatak and reconnects. In 2000 a 1 km long proglacial has formed at the main terminus. Distributary termini 1,2 and 4 all have proglacial lakes. The snowline in 1987 and 2000 is 800-825 m. By 2015 there are five ending in lakes, with Lake 6 having retreated out of a lake basin. A lake has formed at the new distributary terminus at Lake 3. The two tributaries to the north indicated with arrows each retreat approximately 1 km from 1987 to 2015 and in both cases are no longer calving termini. The main glacier terminus has retreated into a proglacial lake, with a retreat of 2 km from 1987 to 2015. The lowest 1.5 km has a low slope and peripheral lakes suggesting the lake will expand substantially as Benito Glacier retreat continues. The transient snowline in 2015 is at 900 m. In 2021 a significant iceberg 0.4 km2 has calved off the terminus. The terminus has retreated 2900 m from 1987-2021 with the lake area expanding to 2.8 km2. The lower 1.5 km of the glacier remains low sloped suggesting significant lake expansion is ongoing. The glacier no longer reaches the former proglacial lake 2 or 6. Proglacial lake 1 has drained. Proglacial lake 2,3, and 4 continue to expand. The snowline on Feb. 6 2021 is at 875-900 m, rising to 925-950 m by March 16, 2021.

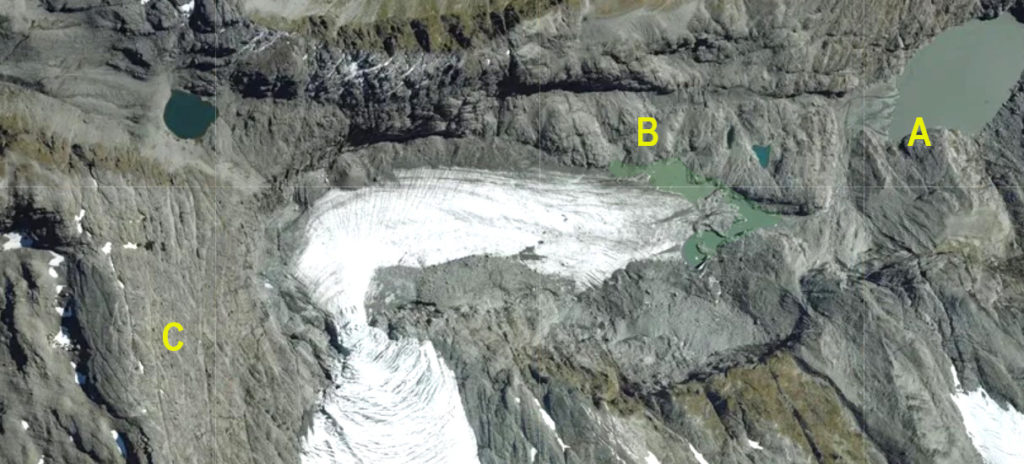

March 17, 2021 Landsat image indicating iceberg located off front of Benito Glacier

Benito Glacier comparison in Landsat images from 1987 and 2015 indicating the terminus position in 1987 red arrows, yellow arrows the 2015 terminus positions. Locations 1-6 are current or former distributary terminus locations. purple arrows where glacier thinning is expanding bedrock areas. The snowline is indicated by purple dots