Figure 1. Global Alpine glacier annual mass balance record of reference glaciers submitted to the World Glacier Monitoring Service.

Each year I write the section of the BAMS State of the Climate on Alpine Glaciers. What follows is the initial draft of that with a couple of added images and an added paragraph.

The World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS) record of mass balance and terminus behavior (WGMS, 2015) provides a global index for alpine glacier behavior. Globally in 2015 mass balance was -1177 mm for the 40 long term reference glaciers and -1130 mm for all 133 monitored glaciers. Preliminary data reported to the WGMS from Austria, Canada, Chile, China, France, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Norway, Russia, Switzerland and United States indicate that 2016 will be the 37th consecutive year of without positive annual balances with a mean loss of -852 mm for reporting reference glaciers.

Alpine glacier mass balance is the most accurate indicator of glacier response to climate and along with the worldwide retreat of alpine glaciers is one of the clearest signals of ongoing climate change (Zemp et al., 2015). The ongoing global glacier retreat is currently affecting human society by raising sea-level rise, changing seasonal stream runoff, and increasing geohazards (Bliss et al, 2014; Marzeion et al, 2014). Glacier mass balance is the difference between accumulation and ablation. The retreat is a reflection of strongly negative mass balances over the last 30 years (Zemp et al., 2015). Glaciological and geodetic observations, 5200 since 1850, show that the rates of early 21st-century mass loss are without precedent on a global scale, at least for the time period observed and probably also for recorded history (Zemp et al, 2015). Marzeion et al (2014) indicate that most of the recent mass loss, 1991-2010 is due to anthropogenic forcing.

The cumulative mass balance loss from 1980-2015 is -18.8 m water equivalent (w.e.), the equivalent of cutting a 21 m thick slice off the top of the average glacier (Figure 2). The trend is remarkably consistent from region to region (WGMS, 2015). WGMS mass balance based on 40 reference glaciers with a minimum of 30 years of record is not appreciably different from that of all glaciers at -18.3 m w.e. The decadal mean annual mass balance was -228 mm in the 1980’s, -443 mm in the 1990’s, –676 mm for 2000’s and – 876 mm for 2010-2016. The declining mass balance trend during a period of retreat indicates alpine glaciers are not approaching equilibrium and retreat will continue to be the dominant terminus response. The recent rapid retreat and prolonged negative balances has led to some glaciers disappearing and others fragmenting (Figure 2)(Pelto, 2010; Lynch et al, 2016).

Below is a sequence of images from measuring mass balance in 2016 in Western North America from Washington, Alaska and British Columbia. From tents to huts, snowpits to probing, crevasses to GPR teams around the world are assessing glacier mass balance in all conditions.

[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”7″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_imagebrowser” ajax_pagination=”1″ template=”/nas/wp/www/sites/blogsorg/wp-content/plugins/nextgen-gallery/products/photocrati_nextgen/modules/ngglegacy/view/imagebrowser-caption.php” order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]

Much of Europe experienced record or near record warmth in 2016, thus contributing to the negative mass balance of glaciers on this continent. In the European Alps, annual mass balance has been reported for 12 glaciers from Austria, France, Italy and Switzerland. All had negative annual balances with a mean of -1050 mm w.e. This continues the pattern of substantial negative balances in the Alps continues to lead to terminus retreat. In 2015, in Switzerland 99 glaciers were observed, 92 retreated, 3 were stable and 4 advanced. In 2015, Austria observed 93 glaciers; 89 retreated, 2 were stable and 2 advanced, the average retreat rate was 22 m.

In Norway, terminus fluctuation data from 28 glaciers with ongoing assessment, indicates that from 2011-15 26 retreated, 1 advanced and 1 was stable. The average terminus change was -12.5 m (Kjøllmoen, 2016). Mass balance surveys with completed results are available for seven glaciers; six of the seven had negative mass balances with an average loss of -380 mm w.e.

In western North America data has been submitted from 14 glaciers in Alaska and Washington in the United States, and British Columbia in Canada. All 14 glaciers reported negative mass balances with a mean loss of -1075 mm w.e. The winter of and spring of 2016 were exceptionally warm across the region, while ablation conditions were close to average.

In the high mountains of central Asia five glaciers reported data from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia. Four of five were negative with a mean of -360 mm w.e. Maurer et al (2016) noted that mean mass balance in the eastern was significantly negative for all types of glaciers in the Eastern Himalaya from 1974-2006.

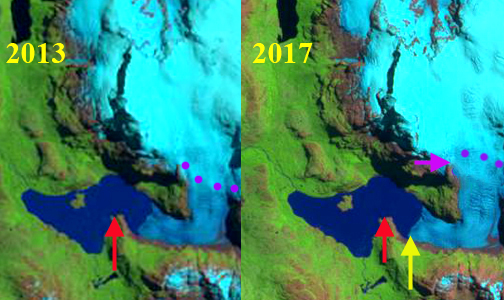

Figure 2. Landsat images from 1995 and 2015 of glaciers in the Clephane Bay Region, Baffin island. The pink arrows indicate locations of fragmentation. Glaciers at Point C and D have disappeared.