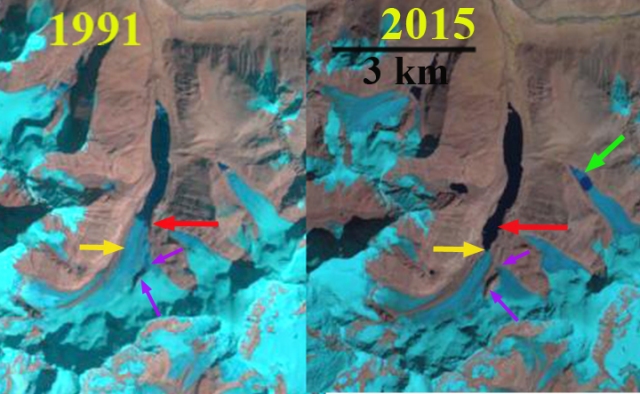

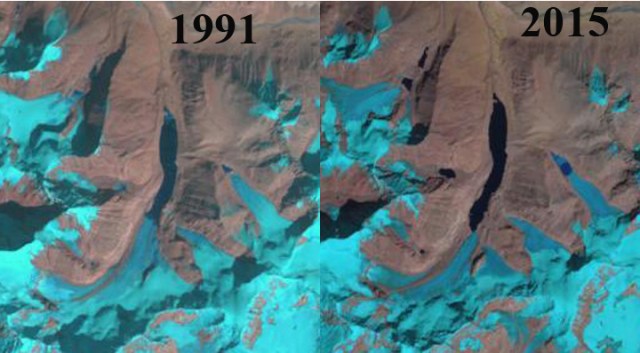

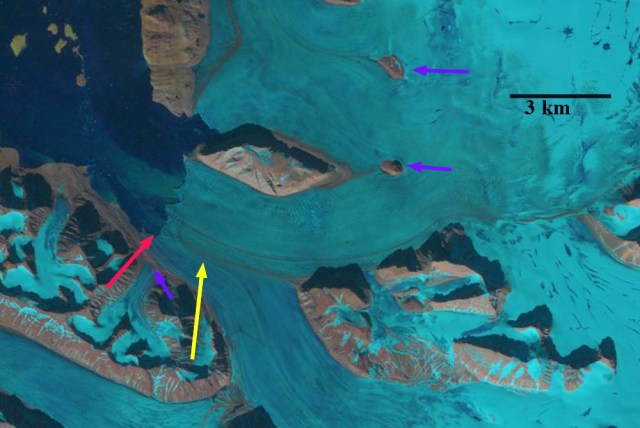

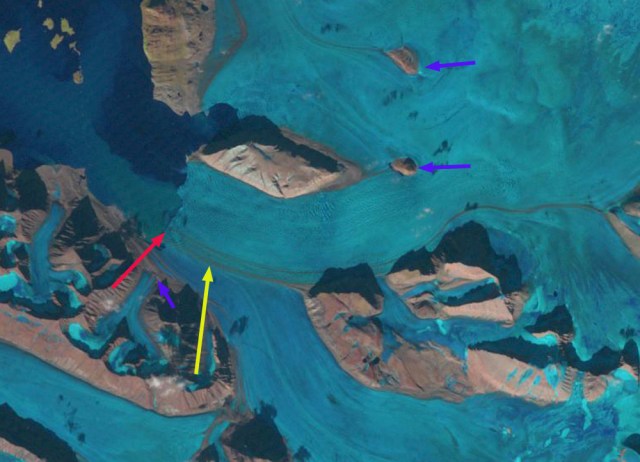

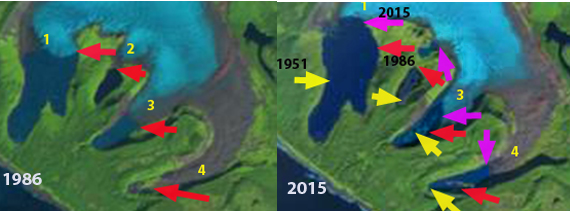

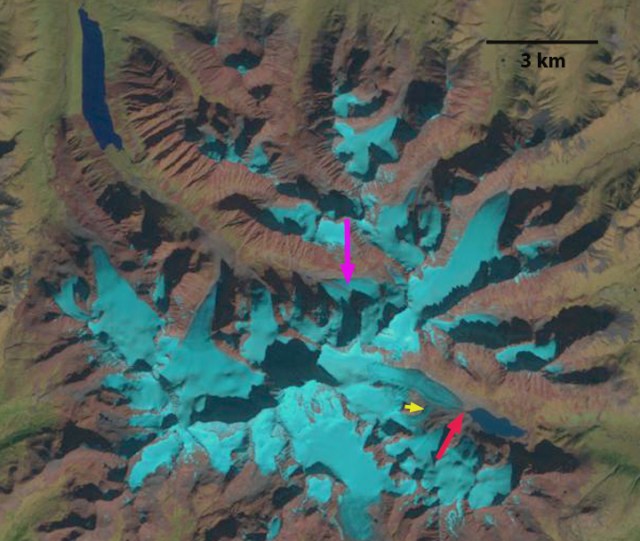

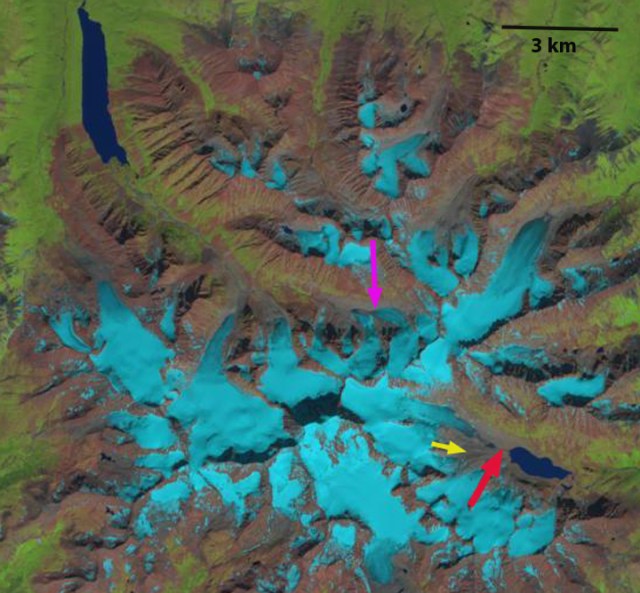

Comparison of 1987 and 2015 Landsat images of Dawes Glacier. Red arrow 1987 terminus, yellow arrow 2015 terminus, pink arrow location where tributaries separated.

Dawes Glacier terminates at the head of Endicott Arm, a 55 km long fjord in southeast Alaska. Dawes is a major outlet glacier of the Stikine Icefield. Larsen et al (2007) observed a rapid thinning of the Stikine Icefield and that Dawes was thinning faster than all but Muir Glacier in Southeast Alaska during the 1948-2000 period. During the period from 1891 when first mapped and 1967 the glacier retreated 6.8 km (Molnia,2008). The retreat has been driven by rising snowlines in the region that has driven the retreat of North Dawes, Baird and Sawyer Glacier.

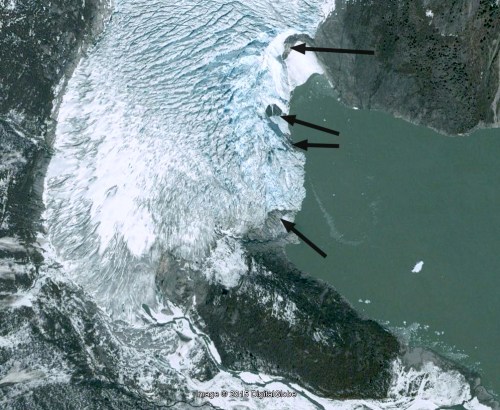

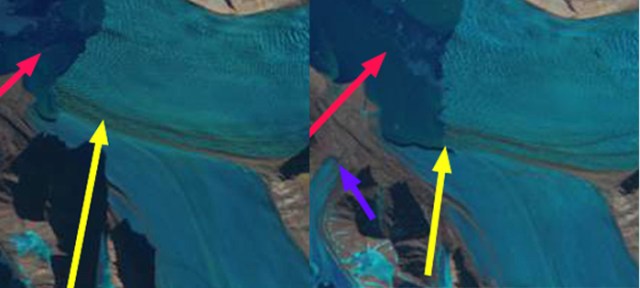

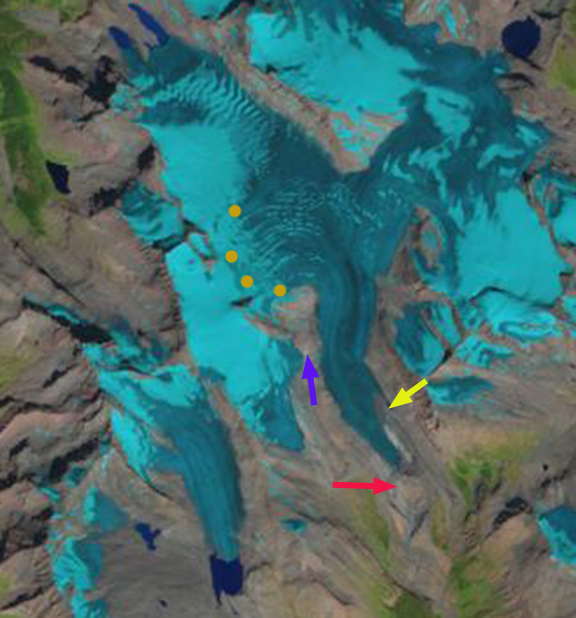

A comparison of 1987 and 2015 Landsat images illustrate recent retreat and thinning of the glacier. The main terminus retreated 1100 m during this interval, a reduced rate from the previous period from 1978 to 1987 the glacier retreated 2.8 km. Key tributaries at the purple and green arrow each have a 30% decline in width. At the pink arrows are three tributaries that fed the Dawes Glacier in 1987 and are now detached. This fragmentation will continue. The reduced inflow and up glacier thinning is ongoing as will the retreat. A key mechanism for retreat over the last century has been calving. The calving rate has declined of late, possibly due to reduced water depth. The 2007 Hydrographic map of the area indicates water depth at the calving front still over 100 m., with a depth of 150 m 1 km down fjord of the terminus (see bottom image). Examination of surface elevation portrayed in Google Earth indicate a relatively sharp rise near the first junction, the surface elevation being at 1400 feet. The trimline is noted with blue arrows, note how much higher above the ice the tramline is at the terminus than at 1400 feet. At this point the northern arm would appear to have a bed above sea level and the main arm at least a much shallower bed. Pelto and Warren (1991) observed the calving rate reduction with water depth in the area. Note the ogives, curved bands, on the northern arm that form once per year at the base of icefall due to seasonal velocity change. The glacier thinning is continuing, but the retreat rate will decline as the fjord head is approached. As calving is reduced harbor seals will be disappointed as they like us are drawn to glaciers.

Google Earth image of Dawes Glacier in 2013. Blue arrows indicate trillion and number are elevation in feet.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game has been monitoring harbor seals in the fjord and noting their use of icebergs and proximal glacier regions. The noted that females travel to pup on the icebergs in the spring and also utilize the are for mating. Because there was little information on where seals that use glacial habitat during pupping and mating season spend the remainder of the year, ADFG attached satellite tags to harbor seals to monitor their movements. In 2008 this data indicated that that adult and sub-adult seals captured in Endicott Arm early summer spent the late summer and fall months in Stephens Passage, Frederick Sound, Chatham Strait, This study is in part prompted by a decline of harbor seals in the Glacier Bay region where they also utilize icebergs, as NPS biologist Jamie Womble explained at the AGU 2015 meetin

1978 Landsat image, blue arrow 1978 terminus, red arrow 1987 terminus and 2015 terminus yellow arrow. Note the improvement in the Landsat imagery.