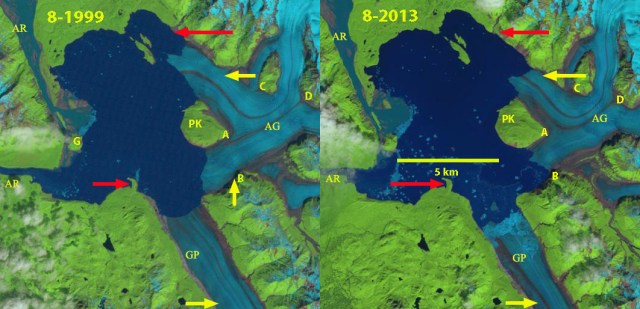

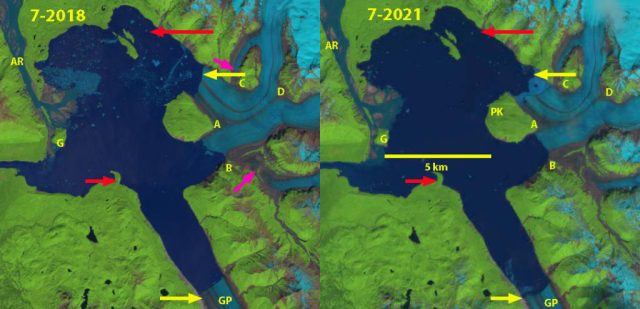

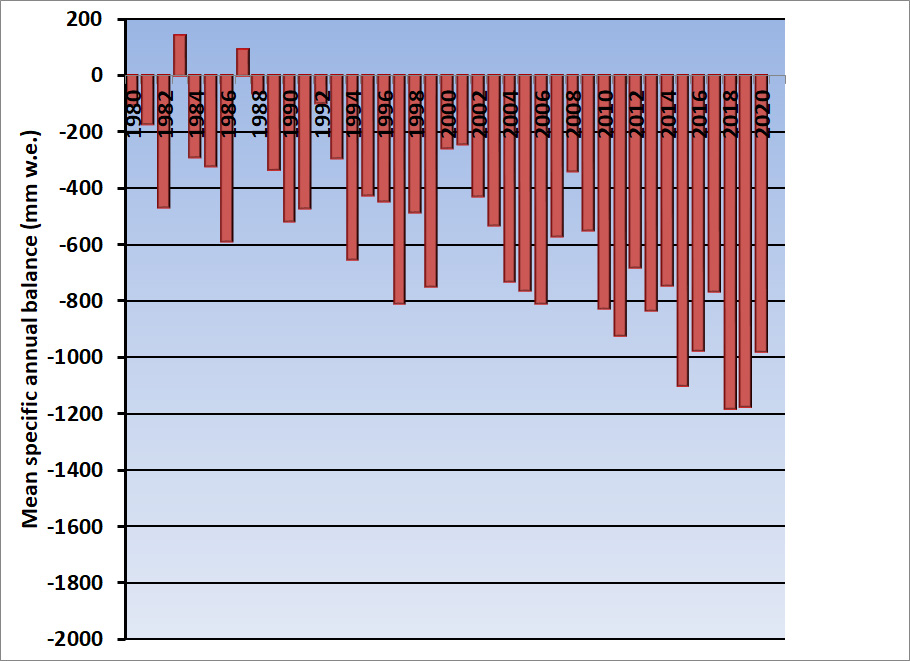

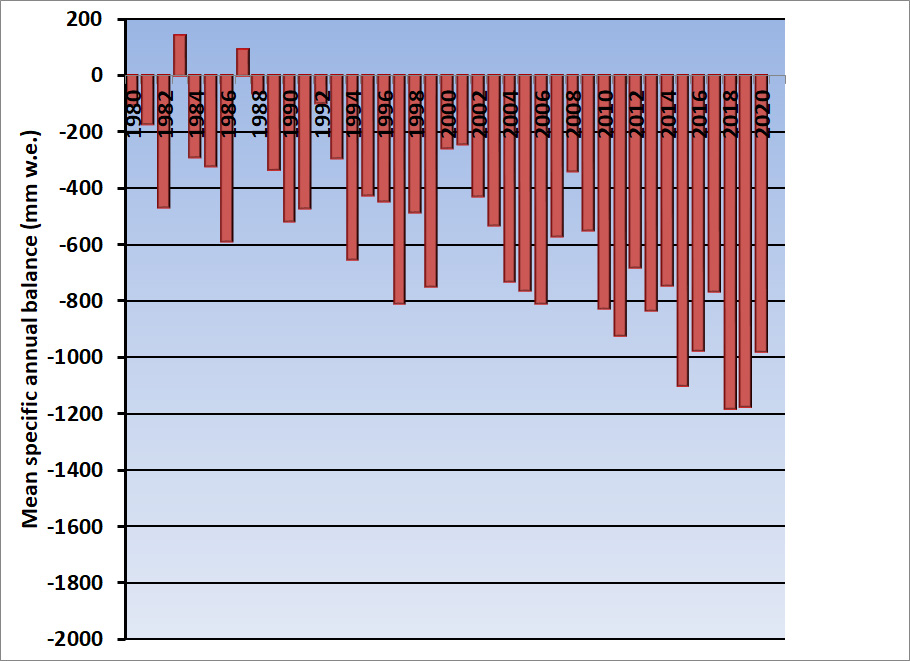

The 32nd annual State of the Climate report was published today. For the 14th year I have written the Alpine Glacier section chronicling their response for the the hydrological 2020/21 utilizing the World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS) data sets. WGMS reference glaciers (30+ years of continuous observation) experienced a mass balance loss of -900 mm w.e., compared to -700 mm w.e. in 2019/20. From 1970-2021 the eight most negative mass balance years were recorded after 2010.

Figure 1. illustrates glacier mass balance for the WGMS global reference glaciers with more than 30 continued observation years for the time-period 1970-2020. Global values are calculated using a single value (averaged) for each of 19 mountain regions in order to avoid a bias to well observed regions.

In 2021, a negative annual mass balance was reported from 31 of the 32 reference glaciers reported to the World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS). The mean annual mass balance of the 32 reference glaciers reporting is -900 mm w.e., this includes data from 12 nations on four continents. This value is not the final regionally averaged global value. This will make 2021 the 34th consecutive year with a global alpine mass balance loss, and the 13th consecutive year with a mean global mass balance below -500 mm w.e..

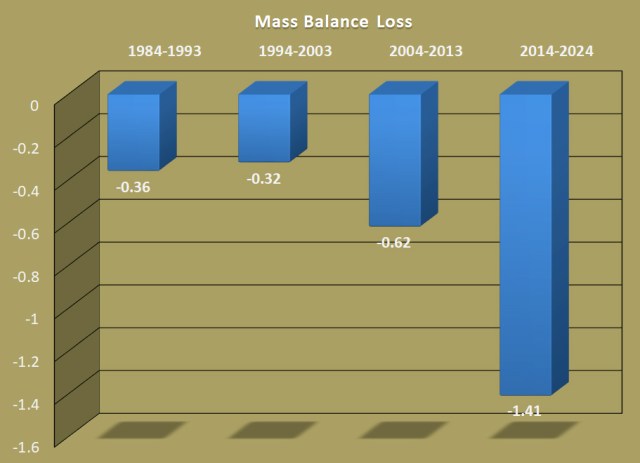

The rate of thinning increased from –527 mma−1 for 2000-2009 to – 896 mma−1 for 2010-2019 (WGMS, 2021). This agrees well with the satellite survey of 200,000 alpine glacier by Hugonnet et al (2021) who identified a thinning rate excluding ice sheet peripheral glaciers of 360 ± 210 mma−1 in 2000 to 690 ± 150 mma-1 in 2019. Alpine glaciers lost a mass of 267 ± 16 Gta-1 from 2000-2019, equivalent to 21 ± 3 per cent of the observed global sea-level rise (Hugonnet et al, 2021). More frequent and intense heat waves continue to take a toll on alpine glaciers.

All 17 reporting glaciers in the Alps had a negative mass balance averaging – 682 mm in 2021. In Austria in 2020, of the 92 glaciers with annual terminus observations 85 (93.4%) withdrew and seven remained stationary (Lieb and Kellerer-Pirklbauer, 2021). This retreat trend will continue in 2021, with another year of mass balance loss.

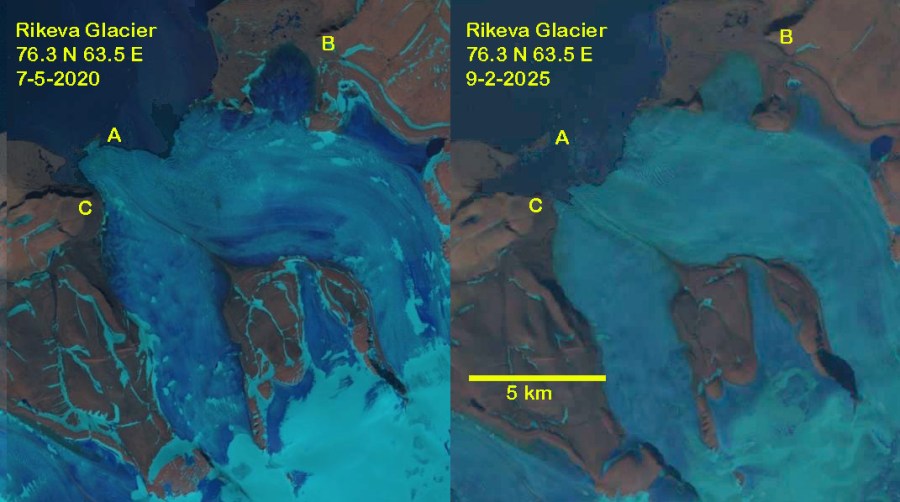

In Norway the six reporting glaciers all had a negative mass balance yielding an average mass balance of -671 mm in 2021. On Svalbard the mean loss of the four reporting glaciers was -227 mm. Iceland completed surveys of nine glacier, all nine had negative balances with a mean mass balance of -1160 mm.

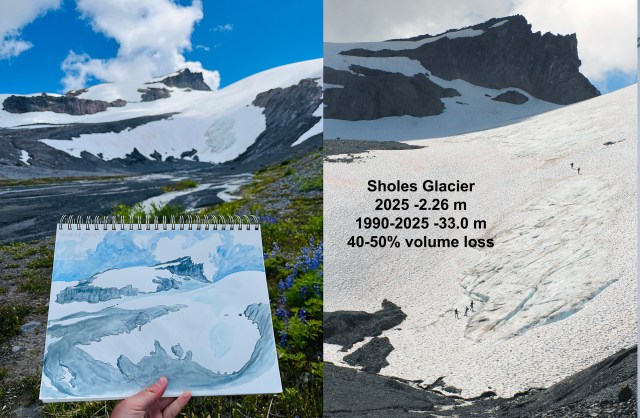

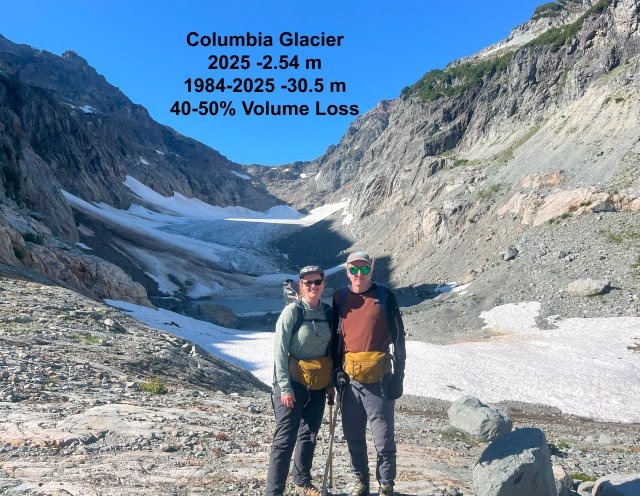

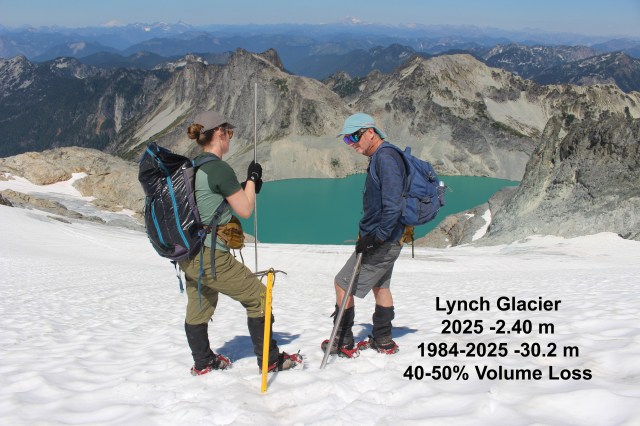

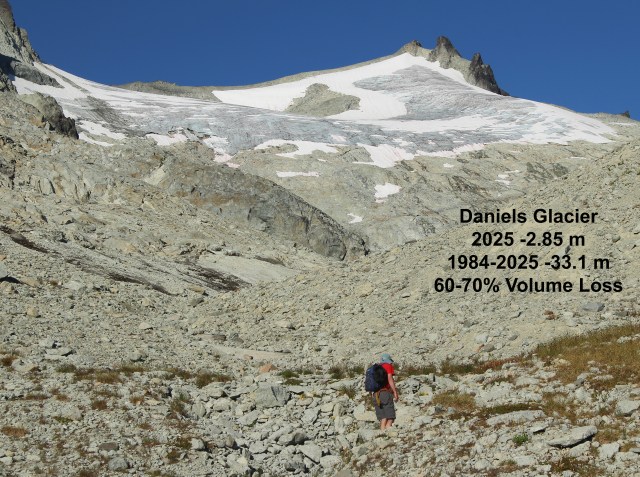

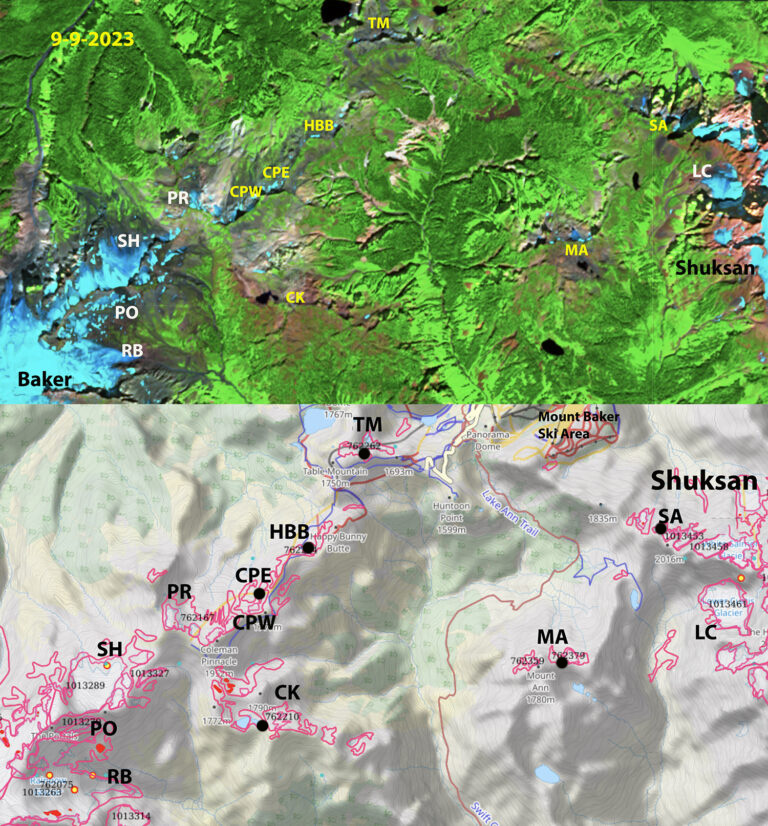

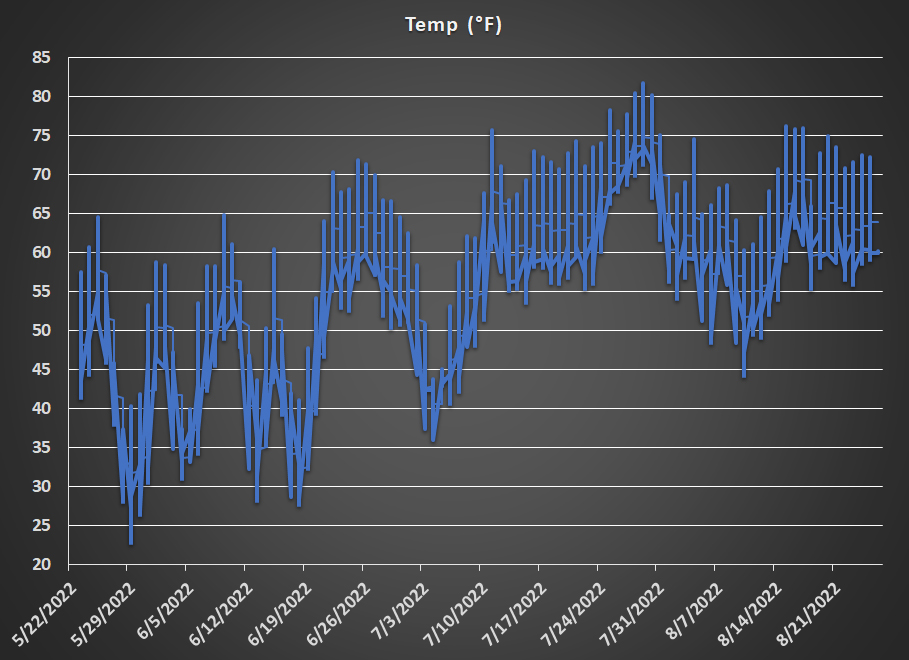

In the Western Canada and the United States and Washington all 14 glaciers observed in 2021 had a negative mass balance averaging -1635 mm. The exceptional heat wave during late June and early July set the stage for the large glacier mass loss. In Alaska three of the four glaciers had a negative mass balance with a mean annual balance of -528 mm.

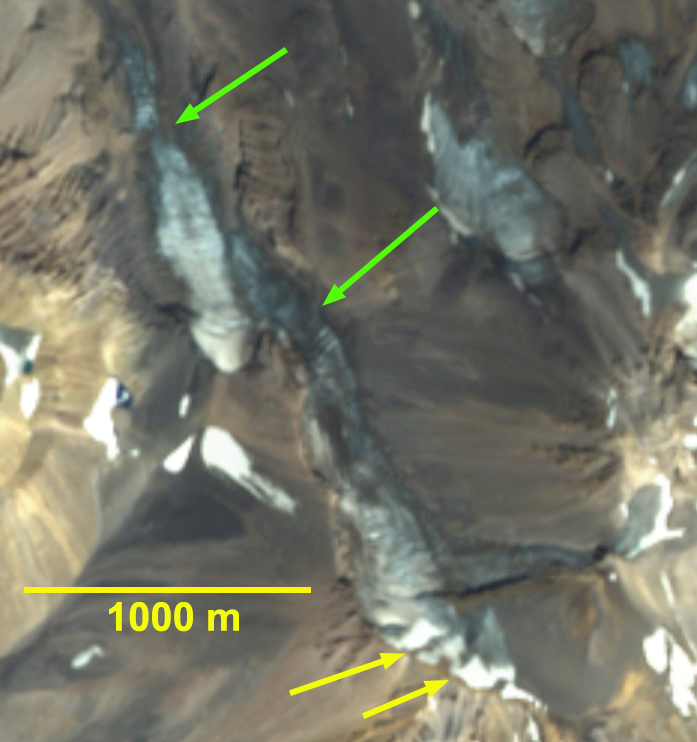

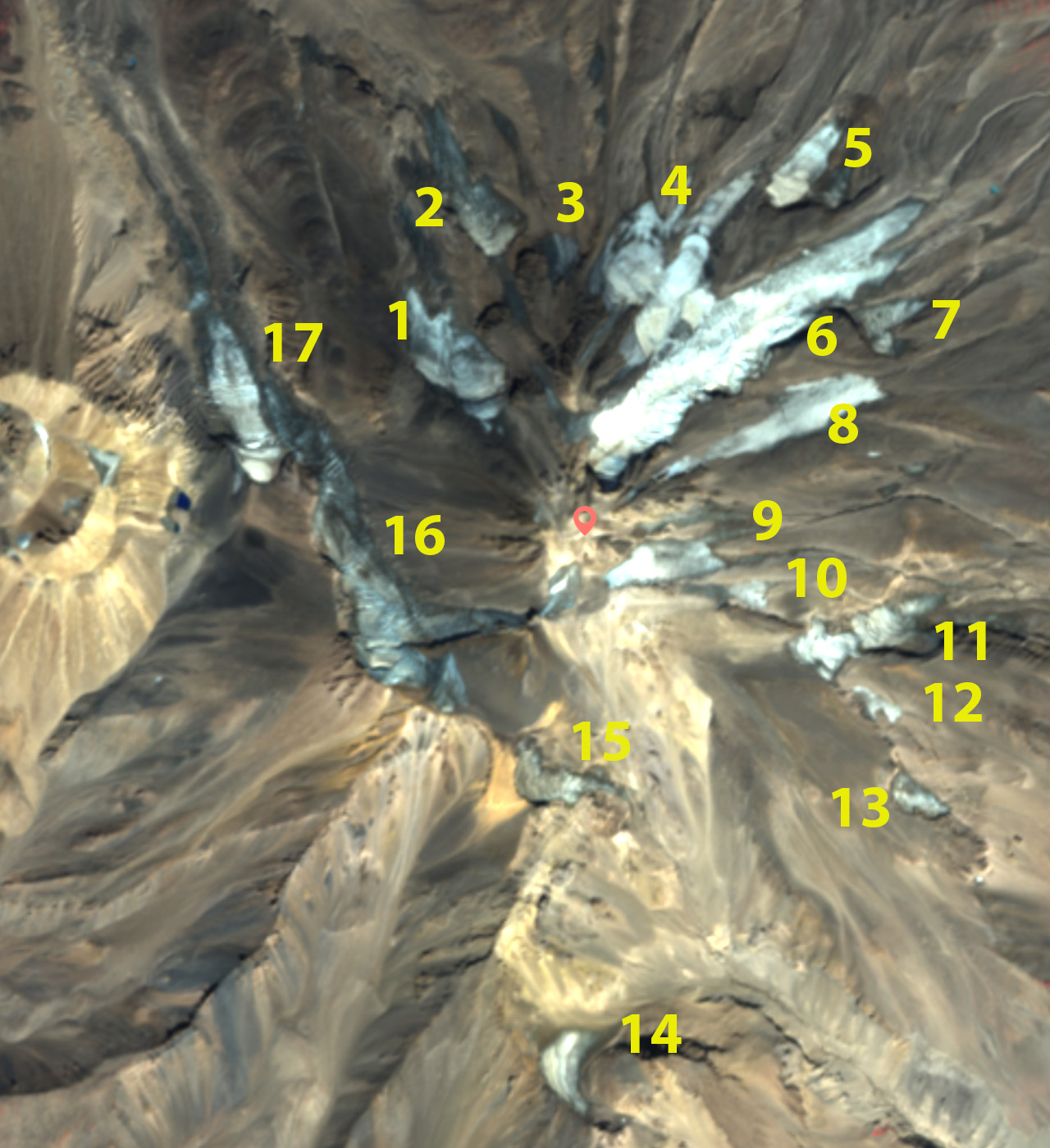

Upper portion of Easton Glacier with a month left in the melt season

In South America, 2021 mass balance data were reported from three glaciers in Argentina, two glaciers in Chile, and one in Columbia, all were negative with a mean of -861 mm. This is greater than the 2000-2018 average loss observed in the Andes of −720 ± 220 mma-1 (Dussaillant et. al., 2019).

In the High Mountain Asia fifteen of eighteen glaciers reported negative balances in 2021. The average mass balance was-468 mm. Early winter of 2021 was warm and dry across the Himalayan Region. This was capped off by record warmth in the Mount Everest region leading to the snow line on glaciers rising and snow free glaciers up to 6000 m (Pelto, et al., 2021). This illustrates that the ablation season no longer always ends when winter begins. The importance of winter conditions was further noted by Potocki et al (2022) who report on an ice core drilled on South Col Glacier on Mount Everest at 8020 m revealing a contemporary sublimation driven thinning of ~2000 mma-1.

References

Dussaillant, I., Berthier, E., Brun, F., Masiokas, M., Hugonnet, R., Favier, V., Rabatel, A., Pitte, P.and Ruiz, L.,2019: Two decades of glacier mass loss along the Andes. Nat. Geosci. 12, 802–808. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0432-5

Hugonnet, R., McNabb, R., Berthier, E. et al 2021: Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature 592, 726–731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03436-z

Lieb, G.K. and A. Kellerer-Pirklbauer 2021: Sammelbericht über die Gletschermessungen des Österreichischen Alpenvereins im Jahr 2020. Letzter Bericht: Bergauf 2/2020, Jg. 75 (145), S. 6–15, https://www.alpenverein.at/

Pelto, M.; Panday, P.; Matthews, T.; Maurer, J.; Perry, L.B., 2021: Observations of Winter Ablation on Glaciers in the Mount Everest Region in 2020–2021. Remote Sens. 13, 2692. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13142692.

Potocki, M., Mayewski, P.A., Matthews, T. et al, 2022: Mt. Everest’s highest glacier is a sentinel for accelerating ice loss. Nature Clim. Atmos. Sci., 5, 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-022-00230-0.

WGMS 2021: Global Glacier Change Bulletin No. 4 (2018-2019). Zemp, M., Nussbaumer, S. U., Gärtner-Roer, I., Bannwart, J., Paul, F., and Hoelzle, M. (eds.), ISC(WDS)/IUGG(IACS)/UNEP/UNESCO/WMO, World Glacier Monitoring Service, Zurich, Switzerland, 278 pp., doi:10.5904/wgms-fog-2021-05.

World Glacier Monitoring Service: Fluctuations of Glaciers (FoG) Database

DOI for current scientific data (Identifier): 10.5904/wgms-fog-2021-05

https://wgms.ch/data_databaseversions/