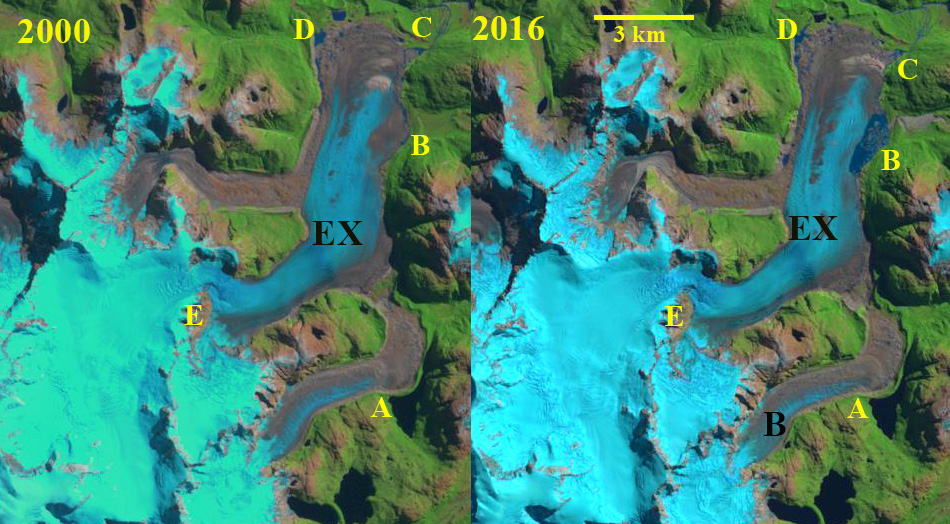

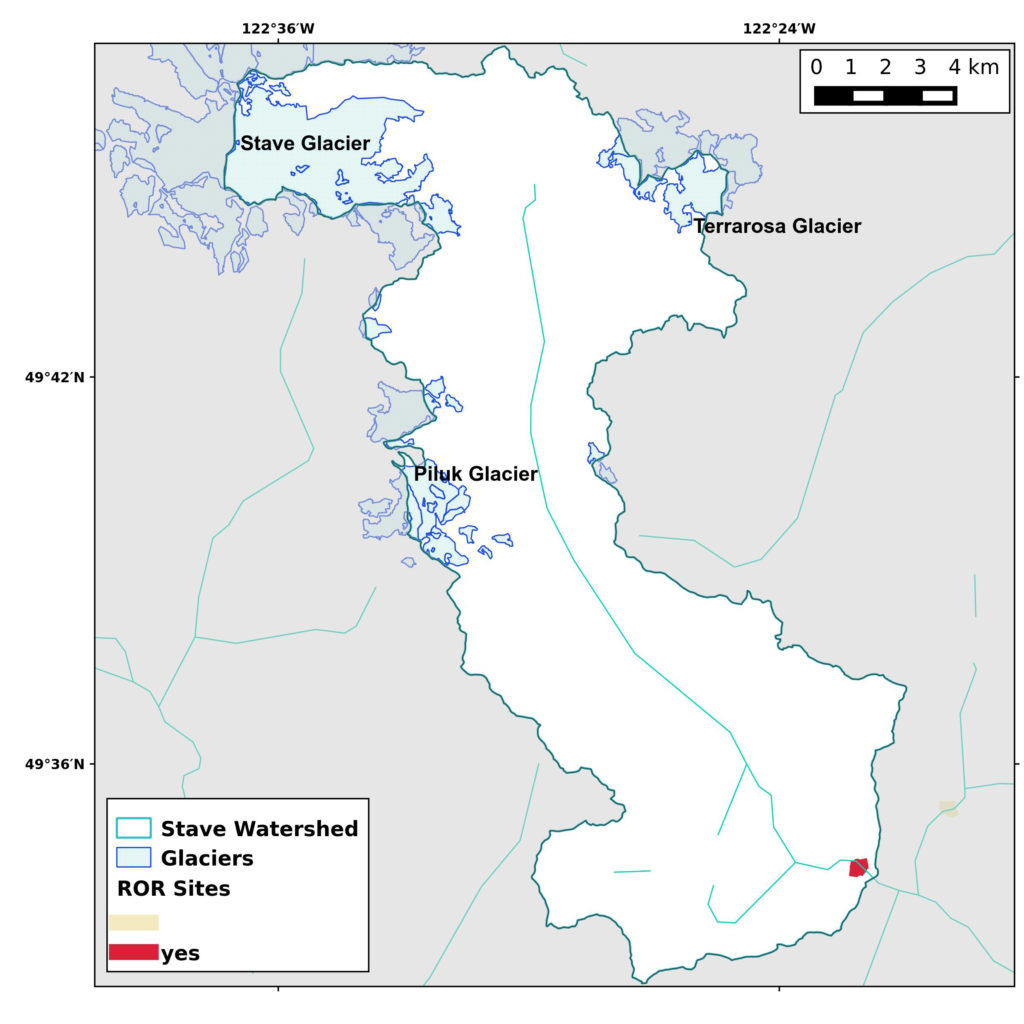

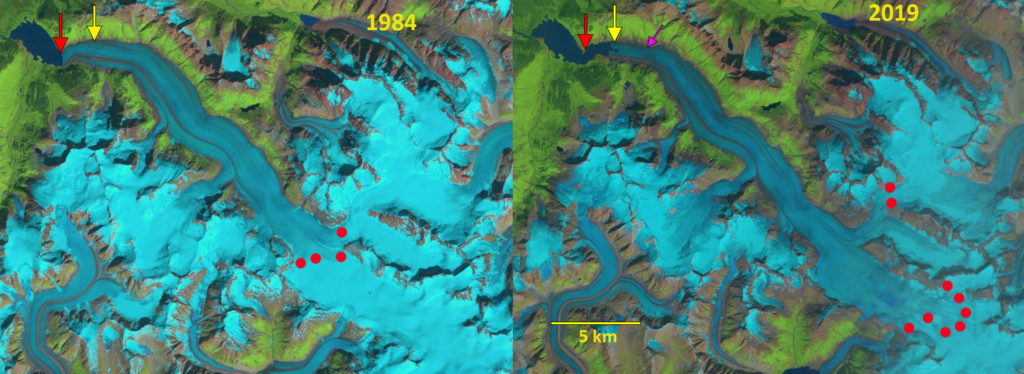

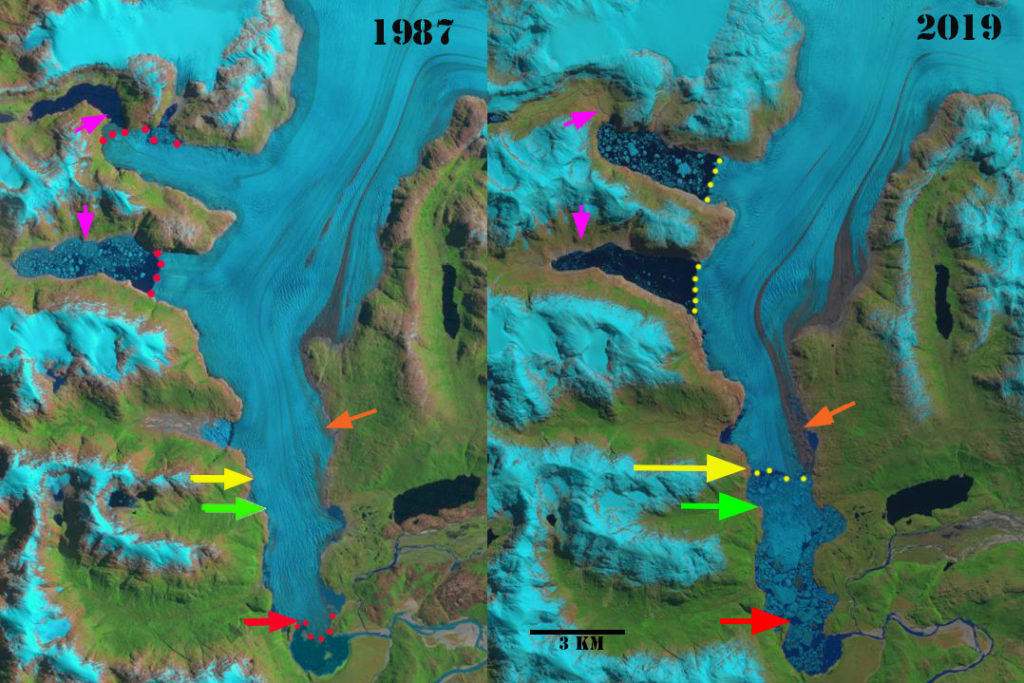

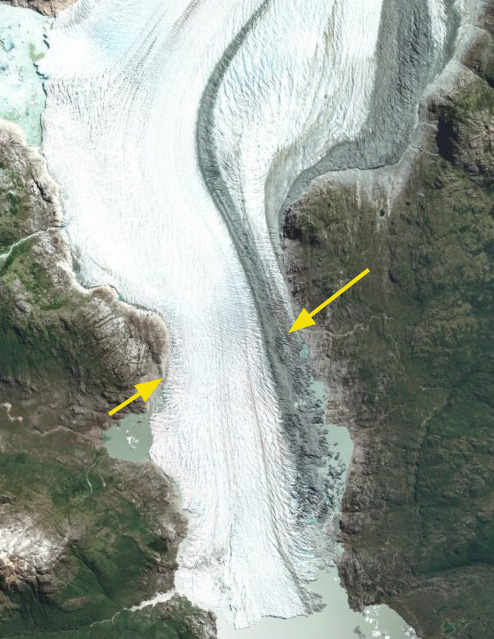

Exploradores Glacier (EX) in 1987 Landsat and 2020 Sentinel image. Points A-E are consistent locations discussed. B=Bayo Glacier.

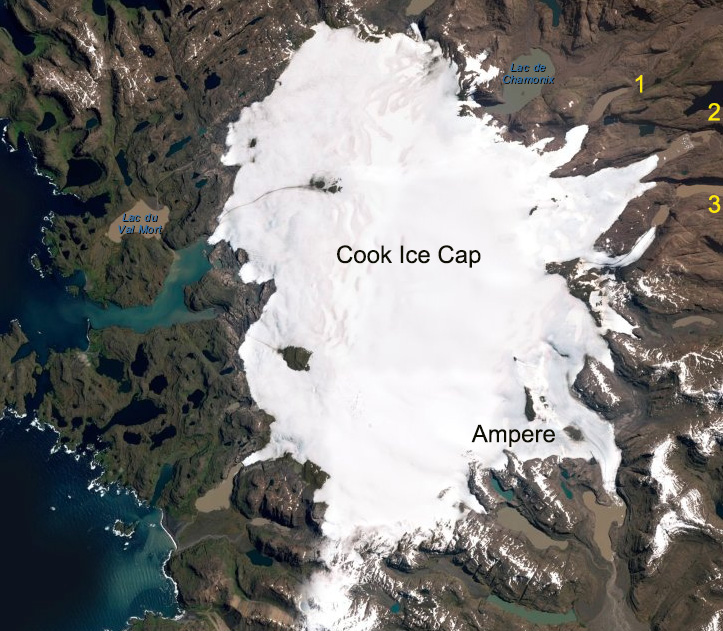

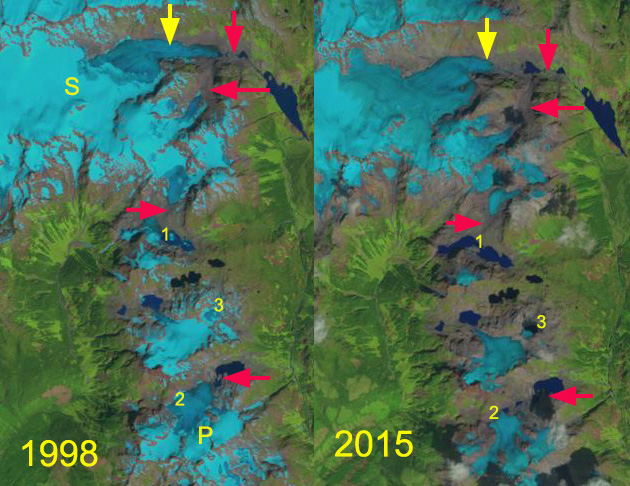

Exploradores Glacier is an outlet glacier at the northeast corner fo the Northern Patagonia Icefield (NPI). Glasser et al (2016) note the recent 100 m rise in snowline elevations for the NPI, which along with landslide transport explains the large increase in debris cover since 1987 on NPI from 168 km2 to 306 km2 On Exploradores Glacier debris cover expanded by 5.5 km2 from 1987-2015. Loriaux and Casassa (2013) examined the expansion of lakes on the Northern Patagonia Ice Cap. From 1945 to 2011 lake area expanded 65%, 66 km2. Davies and Glasser (2012) noted the fastest retreat during the 1870-2011 period was from 1975-1986 for Exploradores Glacier. Here we examine the response of the glacier to climate change from 1987 to 2020.

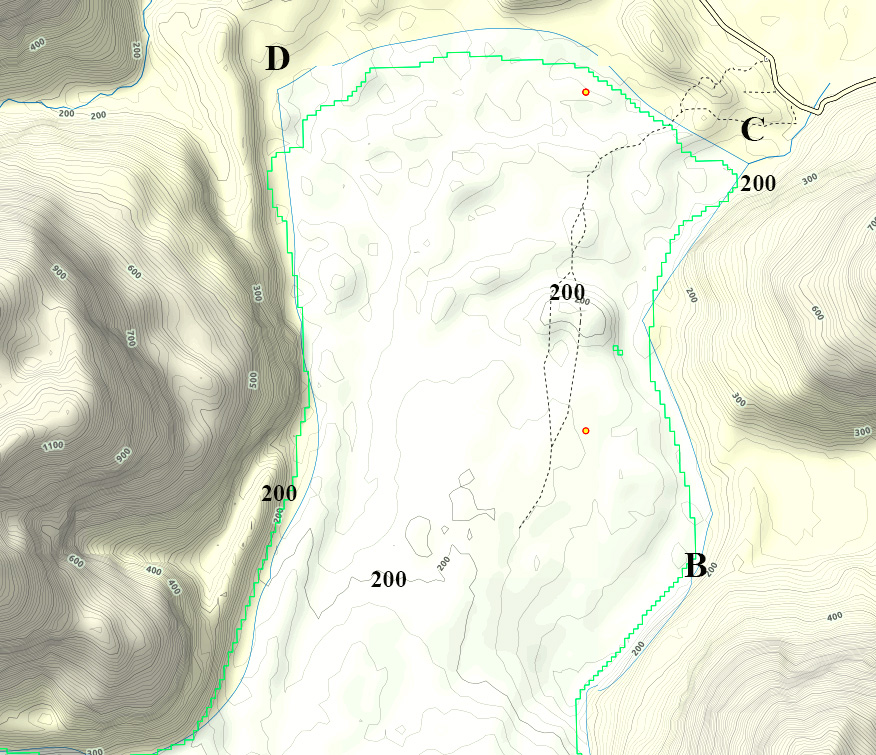

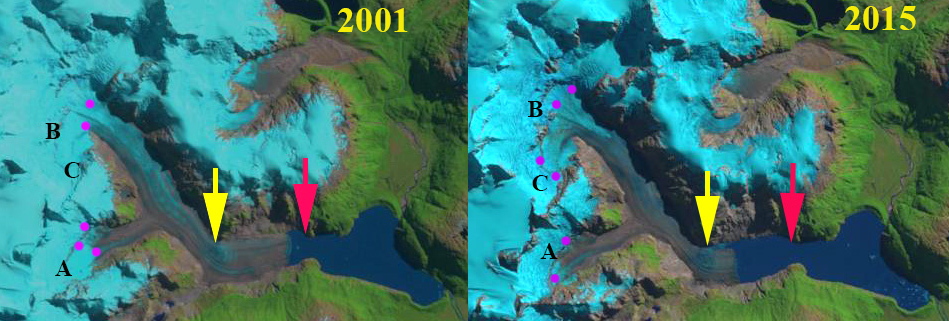

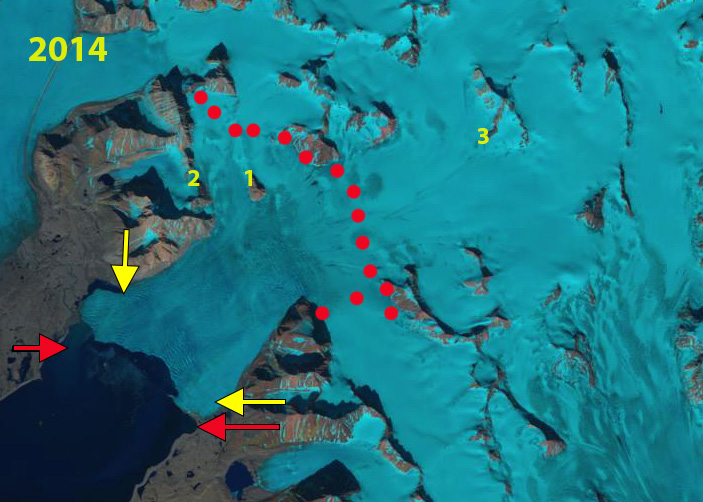

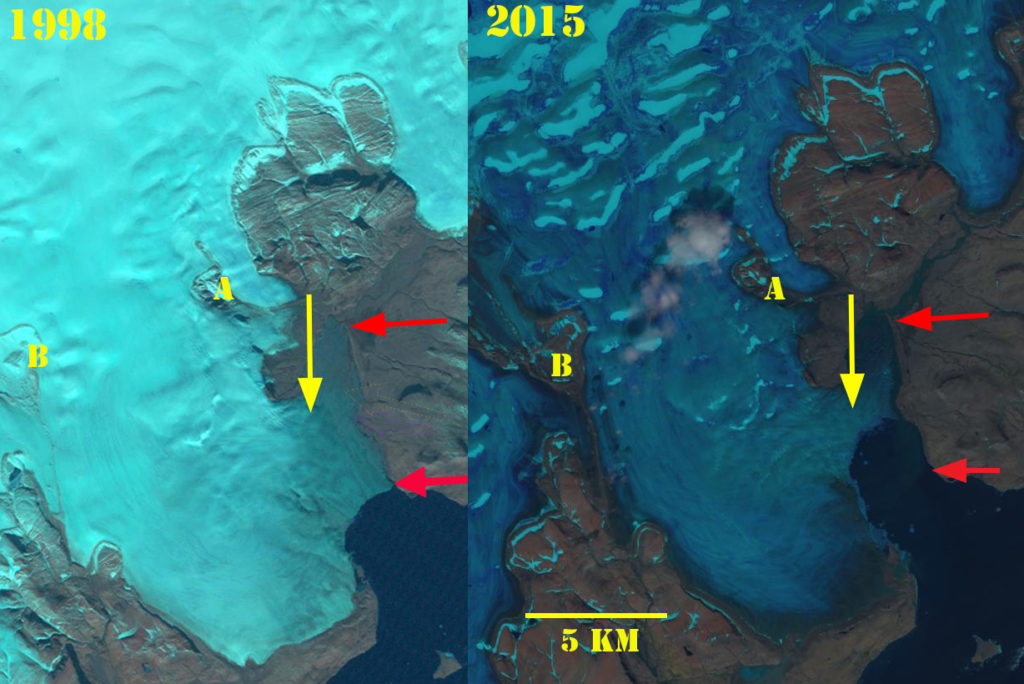

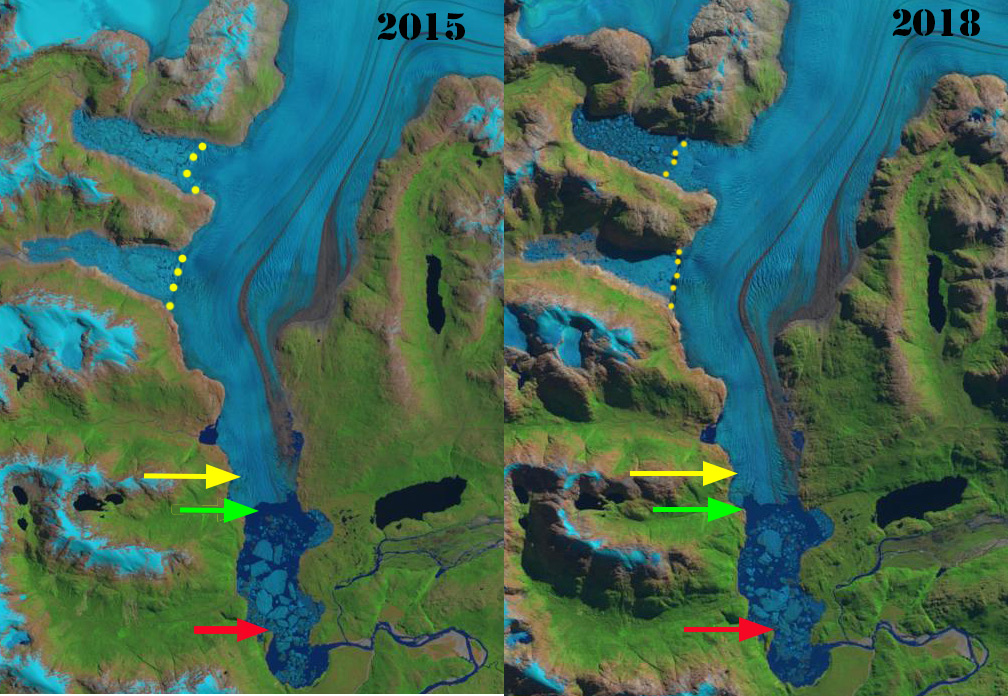

In 1987 Exploradores Glacier has a 12 km2 terminus lobe with a couple of small proglacial pond with a total area under 0.2 km2 near Point D. The snowline is at 1400 m near Point E. A small lake is impounded by a lateral moraine of Bayo Glacier at Point A. In 2000 there is now a single small pond near Point D and a small proglacial pond 0.1 km2 near Point C. The snowline is at 1400 m near Point E. In 2016 small fringing proglacial ponds exist near Point C and D. A substantial proglacial lake has developed at Point B with an area of ~1 km2 on the east margin of the glacier. The impounded lake at Point A has not changed. In 2020 the proglacial ponds have expanded at Point C and D. At Point B the proglacial lake has expanded to ~1.4 km2. The snowline is above Point E at 1500 m. At Point A the impounded lake has drained somewhat and is now at a lower lake level. The lake breached the lateral moraine, which had been increasing in relief from the thinning Bayo Glacier. The snowline on January 1, in the middle of the melt season is already above Point E at 1500 m. The debris cover has extended 5 km up the middle of the glacier from the terminus.

The terminus lobe of the Exploradores Glacier is now collapsing, this is a process that has already occurred at Steffen Glacier, San Quintin Glacier and Colonia Glacier. The terminus lobe is relatively stagnant as indicated by the minimal surface slope. The retreat has been slow compared to adjacent Fiero Glacier. The result will be a new substantial proglacial lake.

Exploradores Glacier (EX) in 2000 and 2016 Landsat images. Points A-E are consistent locations discussed. B=Bayo Glacier.

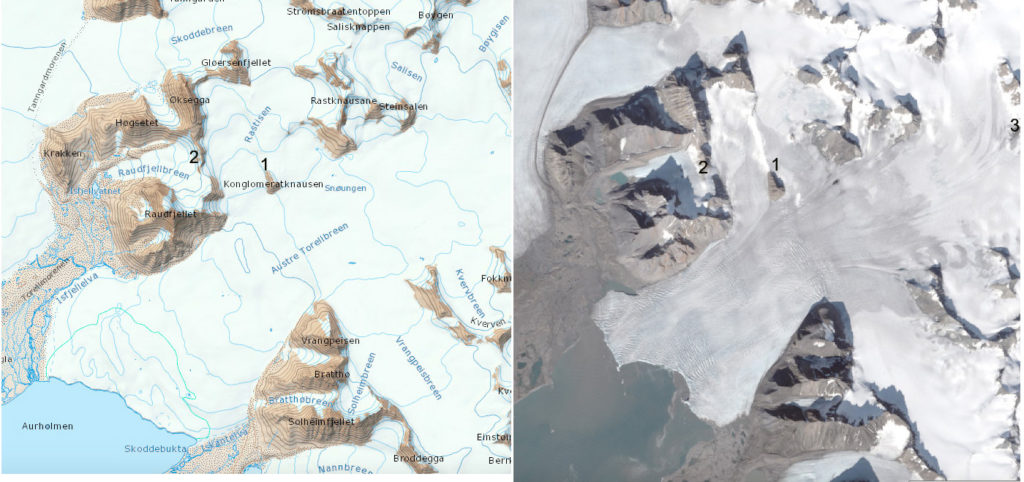

GLIMS view of the terminus indicating the 200 m contour and Point B-D in same location as on images.